I grew up in the West, so I’m inclined towards mighty spaces. Cole and Bierstadt’s Grand Landscapes, though typically 19th-century Romantic and excessive in their depictions of beauty, make perfect sense to me. Our family’s version of a cheap vacation (the only kind we could afford) was camping in magnificent National Parks like Yosemite and Lassen. It was in Yosemite that I learned what wilderness was, hiking hundreds of miles into the back-country, jumping boulders over white water rivers that would kill you with one misstep. For Cole, like us, these places got us as close to the gods as we could possibly imagine being, but at the same time, they represented what we had lost too: any kind of real, unmediated relationship to the natural world, beyond what LL Bean could trick us out with. I find myself repeatedly drawn back to the landscape to explore my own issues, both planetary and personal.

My paintings issue from excess: the way I imagine myself and the world is through an accumulation of marks as information from the senses. For me, too-muchness is a way around self-censorship and towards notating some of the immensity of what is visibly and invisibly available to us. My interest in paintings that describe worlds came about as a reaction to the dryness and strategizing of the art world when I first encountered it in the 70s. At that time I thought all artists would want, as I did, to make work as powerful as a Caravaggio or an El Greco, to speak with a strident voice about subversive beauty and metaphysics and all the important things I was learning about for the first time, but what I found instead were drips and stains. Harkening back to both Tintoretto and Bonnard I wanted to make huge paintings of women’s micro-narrative experience; and, within that universe, to explore my own secrets. In the process and over time my paintings became like journals – a space to record the mutterings of a life, the images that cohere out of memory and imagination, to tell their own story of interiority.

Gradually I learned to pierce the space of the flat plane and find landscapes that mirrored a similar interiority to those earlier works. I was drawn to landscape painting in order to see more and use space to make order and disorder out of the unrolling of events within the confines of a single rectangle. Those landscapes invited you to enter them more and more deeply, in a kind of quintessential feminine space. I began to notice that the abstract patterns I would find in the compositions of those paintings were making a peculiar kind of sense out of my experiences, giving me the components in abstract form as well as in representation to tell my own story.

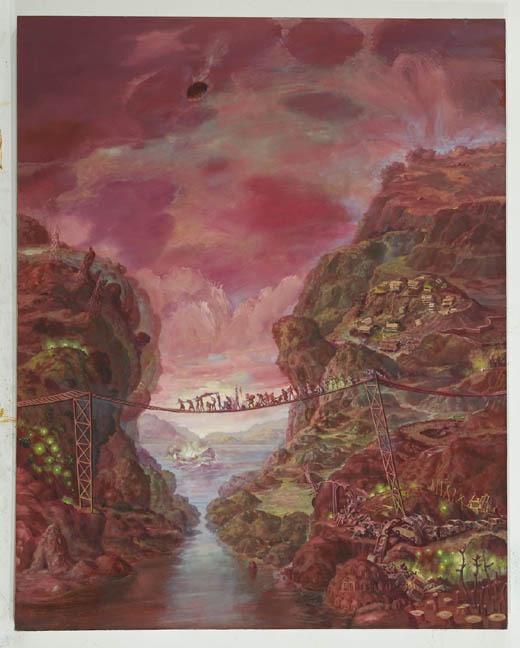

Since then I’ve been making paintings that tell stories within stories, like advent calendars run amok, but in these later paintings I’ve wanted my work to be more incisive and function as records of a sort: to name names, point fingers, show some of the darker corners of American history—greed, empire building, corporate overreach– and find imagery that depicts some of the so-far invisible consequences of our reliance on dirty energy sources and toxic farming practices. I wanted to see what sense I could make of the contemporary landscape after calamities like Hurricane Sandy and the BP oil spill. The paintings describe alternative habitats, mechanisms for storing food and things we can’t live without, like water and books and wild places. I wanted imagery that might suggest other ways we could cope and possibly even flourish in a new extreme climate, and to give my characters things they must tend. I gave them water and tools to stop the burning; the tarred and feathered heads of the Koch brothers; a library of great books to surround themselves with as they contend with the madness of man-made calamities.

I see similar furies to my own simmering in the work of Thomas Cole as he confronted the particular struggles of his time: the Industrial Revolution and the changes it wrought on both the landscape and civil society. Today it’s the invisible nature of our environmental problems that we have to contend with as well as the overt ones. Whether it be Monsanto’s poisons creating “superweeds” and “superbugs,” or the proposed Keystone XL pipeline running stealthily through the Ogallala aquifer, potentially contaminating our biggest underground freshwater supply, the average person can’t see what’s happening to the world, because the causes of toxicity can be thousands of miles away, or simply kept secret.

And yet, as a painter, I am still drawn to Beauty and Art, to the cultural artifacts that made us able to imagine the Great. I believe in powerful imagery that can manifest truth and change minds. Modernism gave us much to admire but, aside from masterpieces like Picasso’s Guernica and a few others, we’ve lived through a century of paintings that have mostly made strides on a formal level and avoided dealing with difficult events in life, giving that domain over to photographers and filmmakers to map the terrain and nature of the earth and its problems. But lately painters like Nicole Eisenman, Sue Coe, Lisa Sanditz and (now deceased) Frank Moore have brought something substantial to our understanding of socio-political and environmental issues, using the power of paint’s materiality and immediacy to bring poetry and nuance to our experience of those problems.

Work of this sort cannot concern itself with aesthetics alone. Minimalism makes no sense to me in light of the range and degree of calamities we face, calamities that call to us to face them down and explore them with the myriad tools we possess as artists. In this exploration something of the sublime might just crop up and show us a different perspective. Even disasters have their weird beauty, if only better to grab our eyeballs and force us to look.

Visions of heaven in every culture I am aware of incline to the excessive, an idea of bounty that might be essential to the psychic survival of each of us, providing us a picture of a state beyond ourselves, beyond the exigencies of everyday life, where what we actually need is amply available. This is the apparatus of transformation—already to be the thing we are not.

The artworks by Julie Heffernan published in this post are currently on national tour in the traveling museum exhibition, Environmental Impact.

Born in Peoria, Illinois Julie Heffernan received her BFA in Painting and Printmaking from the University of California, Santa Cruz and her Masters of Fine Art in Painting from the Yale School of Art. Her lush paintings are manifestations of Heffernan’s Baroque sensibilities and rich knowledge of art history—the interior spaces of her compositions often refer to grand ballrooms and ornate drawing rooms, while the exteriors are placed within abundant forests and imagined worlds. Something of a contemporary surrealist, her compositions are drawn from the peculiar, nonsensical narratives of her dreams. As a result of drawing so directly from the images of her subconscious, Heffernan considers much of her work as a kind of self-portrait and titles them as such.

Born in Peoria, Illinois Julie Heffernan received her BFA in Painting and Printmaking from the University of California, Santa Cruz and her Masters of Fine Art in Painting from the Yale School of Art. Her lush paintings are manifestations of Heffernan’s Baroque sensibilities and rich knowledge of art history—the interior spaces of her compositions often refer to grand ballrooms and ornate drawing rooms, while the exteriors are placed within abundant forests and imagined worlds. Something of a contemporary surrealist, her compositions are drawn from the peculiar, nonsensical narratives of her dreams. As a result of drawing so directly from the images of her subconscious, Heffernan considers much of her work as a kind of self-portrait and titles them as such.

This post is part of the newly launched MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems. Contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the new space.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/excess/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.