From New Mexico to Israel, Wagner has sought out works of art that lend credence to the all-too real truth of environmental despoliation occurring worldwide at this point in time. Ironies cascade, memories cry out to be forgotten, while others are recalled by way of vivid and disturbing testimony. In each work of art there is a quintessential nerve ending gone awry that beckons for remedy, re-attunement, some other emotion beyond mere sorrow and loss.

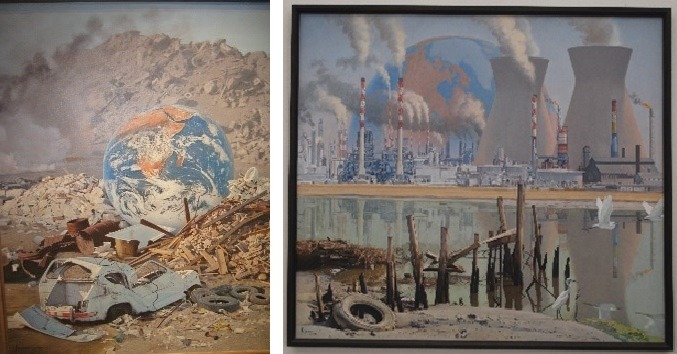

These artworks are populated by tragedy, or the symbol of such: Life receding into mute dumps, silent pits, poisoned cavernous wilds that deny wilderness in favor of human depravity. There are dead birds, desiccated horizons, ruined rivers, and escalation of toxic layers that mimic all that art better left to our nightmares. Yet, by nature of the assemblage and its theme, these artists and their creations have given us melancholy to think about and be moved by. Such is the chaos that enshrouds human contradiction in setting after setting. This collaborative topography leaves no stone unturned in its ruthless laying bare of what it is, from quadrant to quadrant, neighborhood to neighborhood, that humankind is wreaking on the Earth in the name of occupation.

Fake hay, homes abandoned, lives lost. There are fumes, unchecked hideous developments, broken-down dreams, oil spills, death and despair. All this in the name of human evolution beside the fantasies gone haywire of some perverse paradise that once was and, by all accounts, will never be again.

If this seems too harsh a commentary, the amalgamation of precisely articulated curatorial particulars makes it clear that this is no exaggerated desperation but the world of our own doing. If we are so desperate, why, then, do we continue to add insult to injury?

Write’s Wagner:

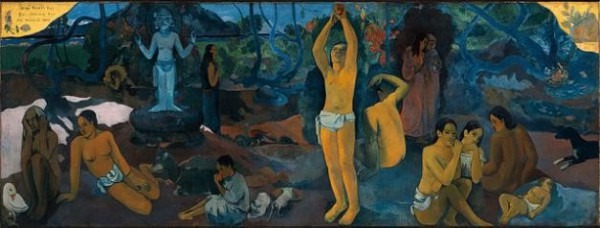

“Traditional art generally depicts nature in all of its glory, often in beautiful, pristine conditions. The 75 paintings, photographs, prints, installations, and sculptures in Environmental Impact are different than traditional works of art because they deal with numerous, ominous environmental issues ranging from the implications of resource development and industrial scale consumption, to major oil spills, the perils of nuclear energy, drought and diminishing water resources, global warming, and many other modern phenomena that impact people and the other inhabitants which populate the planet today.”

From polar bears and dolphins to frogs, homes built on prime agricultural land, to the Apocalypse itself – this exhibition is unique. What do Rising Tides and Reno, Nevada have in common? Vancouver Island or a shrimp farm (formerly a mangrove) in Vietnam? These relationships are rendered sobering and unambiguous through the very humanity implicated in Environmental Impact. A pile of tires takes on the entire universe, as does a holding pond. The images in numerous media are, collectively, the heartbreaking truth –done beautifully, provocatively, barren, rich, resplendent, depressing, horrifying– all of the above and more. It is a terrifying prospect, taken together, of the human presence on earth.

In the juxtaposition of Walter Ferguson’s little girl building sand castles beside a half–sunken tire in Save the Sea Shore, and Lucia deLeiris’ intoxicating image of Antarctica’s Ross Sea, are admixed the two most troubling of all intimations: a little girl’s daydream, untroubled, perfect, intoxicating, and a distant nuance from the end of the world, as we now have come to recognize the signs – cracks in the ice, a melting continent, global warming, and the utter dismantling of a planet where life has evolved over the course of 4 billion+ years.

Antarctica’s ice is nine miles deep, atop rock. But that is all changing now. Not the rock, but the veritable pH of the Southern Antarctic Ocean convergence waters which, in turn, fuel the food chain essential for phytoplankton, krill and the entire marine mammal and seabird ecosystems of the Southern Hemisphere. The late explorer Thor Heyerdahl first detected DDT in the fatty tissues of penguins as early as 1968. Rachel Carson helped change all that, but so have the artists. From smokestacks to garbage dumps to birds with nowhere to migrate, Environmental Impact tells a story teeming with collaborative efforts by painters and scientists alike: a chronicle of woes at the beginning of the 21st century. These are not mere “inconvenient truths” but shattering realities.

Scott Greene’s Oasis, a recent oil on canvas, in some ways says it all: dead lambs on a seeming altar that has taken the great Jan Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb 1430–1432) and transmogrified it into the human story: a sacrificial lamb whose silent repose, in death, betrays all of the innocence lost, the beauty that belies the truth of our biospheric mortality. This is no accident, but the forensic evidence, sealed in artistic nuances of great insight, that we have created a monster by our own undoing. Yet, paradoxically and without forgiveness, we are also a combined force of a witness, a species clearly in tune with its own hemorrhaging powers and the sensibility and coherence of thought to know we are in trouble and something must be done to correct a mistaken course.

As we approach 9, 10 possibly 11 or 12 billion Homo sapiens, our reckless indifference to an ungainly foothold tells a story that Wagner has carefully laid out with 75 brilliant works of contemporary art and commentary on the current ecological crisis. This was not an easy task of fitting pastoral parts together, or combining the best of a certain theme –horses, women sowing, men in court, even smokestacks. Indeed, there has rarely if ever been such an exhibition wherein the madness of civilization has been so forcefully and elegantly told. Such beauty and rich intelligence brought to bear on so much ill-boding imagery. So colossal and enduring a menace as that represented by ourselves, shared in so beautiful a choreography.

It is as if beauty has been harnessed to foretell the end, not unlike those wondrous engines of doom pictured by Gustave Doré in his illustrations of Dante’s Inferno, or of Don Quixote smacked silly by a windmill. We are on the ground, here –near death.

Currently on display in Environmental Impact

This exhibition –which could not have been easy to assemble– is a harrowing wake-up call and one that cannot, must not be ignored. If a “wildfire” in the Sacramento Delta, a landslide, freakish genetic engineering or the critically endangered Siberian Tiger, whose numbers are statistically approaching zero, are not enough to shake us from our complacent rut, then nothing will. Herein is the art of our age told unsparingly, without rhyme or metrical calm. It is jarring and depressing to the extreme, even as we inevitably marvel at the sheer beauty that humans can make out of misery: the glory inherent in our own destruction, and that of others who cohabit the precious Earth. How is it we can pull this off, one must ponder? How can so much beauty be instinct within the decay and acid rain, gill nets and harpoons that herein are all too recognizable?

Eco-psychologists ponder the strange bedeviling that is our psyche and our out-of-control ego: the greed, callous indifference and outright cruelty of which we are, in part, capable. Capable translates into culpable, and Environmental Impact makes it clear and palpable that there are no happy zoos. That jaguars are losing ground and smelters are demolishing our children’s hope of clean air to breathe. What then? What new art form is likely to arise that can redeem us in the face of a generation that could, if left unchecked, be remembered not for art, or destruction for art’s sake, but for utter and unremitting desolation. Should that be the case, then this exhibition will be remembered as an all too fitting epitaph.

One comes away from this assemblage of fine art with a single hope: a flame of conscience that strangely, whimsically, soulfully wishes for something other than that which is before us. Let us take these measures of the human soul, these reflections on the passing of a generation, to heart and resolve with all the incandescent and the subtle nuances that have come together in this exhibition so as to resurrect some other conclusion: the safety, tranquility, and assuredness of a future for our kind, and by our kind, for all of life on Earth. That is a new kind. A kindness of which we are made, as we are of drawing a bird, a tree, or regarding with hope and with awe and wonder the sunrise and the sunset.

If the history of landscape art has come to naught, then Environmental Impact is indeed a fitting tribute to a terrible end. But, as we would prefer to perceive it, this exhibition is a cautionary tale, done in finery and diversity, and just in time. It tells us with great intelligence, and splendor of what we remains to be accomplished: not more stupid mischief and ecological unraveling, but the active remembrance of things past, and of the possibilities for a new tomorrow.

With an estimated 100 million species still sharing the planet with our kind (if one includes invertebrates and the myriads of bacterial and viral species invisible to the naked eye), there is every reason to be hopeful. To believe that we can succeed. The intelligence and prolific talent enshrined in Environmental Impact makes it abundantly clear that we have what it takes to survive, and to do so with nobility, virtue and generosity.

Picasso’s Guernica reflected the horror of the Spanish Civil War, just as four hundred years of Christian iconography mirrored all that was violent and religious in nature throughout the Renaissance. The countless Christs on the Cross, or the arrow-ridden Saint Sebastian were indicative of a dualism instinct in human nature. Yet, at the same time, those very impulses to depict tragedy were at the core of great art and sociological realism. If ecology is the global religion of the 21st century, then that same Christ-figure, as perceived by so many richly diverse artists, is the Earth herself.

Environmental Impact is no less indicative of seriously troubled times, and possibilities for the dawn.

Michael Charles Tobias, Ph.D. & Jane Gray Morrison President & Executive Vice President, Dancing Star Foundation 2012 © Dancing Star Foundation, dancingstarfoundation.org

This post is part of the newly launched MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems. Please contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the new space.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/reflecting-ecological-doom-resurrection/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.