Allow me to vent a serious frustration: For as much as they like to tout the importance of natural beauty, both the American conservation movement and many of this country’s premier fine art museums have, in recent years, been almost blind in recognizing the power of art—photography, painting and sculpture—to move the masses into action.

How do I know this? Because for the last 30 years I’ve been a national journalist writing about the intersection of environmental issues and wildlife art. During that stretch, the malady Richard Louv dubs “nature-deficit disorder” has become a pandemic.

Short of actually making an excursion into wilderness, how can the senses still be stoked? Studies show that art can function as a gateway.

It’s an amazing, wondrous thing, really, to see what happens when people of both older and younger generations come together and have their imaginations piqued by art. I’ve seen enlightenment occur in real time.

Half a decade ago, Canadian environmentalist Harvey Locke helped organize a provocative traveling exhibition. Its focus: a vast bioregion in the US and Canadian Rockies known as Yellowstone to Yukon. The show, which attracted huge crowds to a pair of prominent venues, compared historic wildlife paintings created long ago with contemporary interpretations by modern artists to highlight threats to wildlife on the landscape.

Hugely impactful, the event served as a springboard for elevating social discussions about climate change, growing human population pressure, and the value of wildlife diversity in the 21st century. Today, museums are struggling to stay relevant, to win over the attention of young people who seem chronically disinterested in anything that isn’t flashing. We oldsters need to do a better job of reminding them they matter and that we want them to step up. We need to have more shared experiences. We need to show we have confidence in their decisions. We need to have more conversations.

Fine art can serve as a potent flashpoint.

“Art and conservation are natural allies—one feeds on the other,” Locke told me. “Art can put you in a frame of mind where you see things different than might not be readily visible otherwise. Artists often pick up on things before they register with the rest of society.”

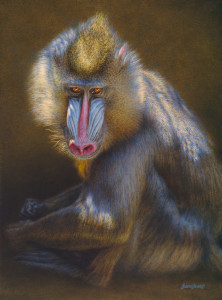

Now, contemplate another exciting exhibition coming in 2017 from internationally-renowned painter Brian Jarvi. Jarvi’s unprecedented tour de force, called An African Menagerie, will feature a panoramic scene comprised of seven interconnected panels stretching 28 feet across and climbing nearly a story tall. Like the grand frescos that rose during the Renaissance, it is still being completed but already takes the breath away.

Brian Jarvi with An African Menagerie in progress © Brian Jarvi

In three decades of writing about wildlife art, I’ve never encountered anything like it. Grouped together are more than 140 different species from sub-Saharan Africa, ranging from charismatic megafauna to a dizzying array of birdlife. Ecologists say many of these creatures could be gone from the wild by the middle of this century. Seeing them presented in mass is both inspiring and gut-wrenching.

The question engaging us is: Are we willing to allow this expression of terrestrial life to vanish from the planet on our watch?

While the scale of Jarvi’s endeavor is unsurpassed for an American wildlife artist, the tradition is one that reads like high notes that have been sung along the trajectory of our own species.

In indigenous pictographs, in Heironymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights and in countless other epochal paintings by visionary women and men, we can trace the influence of art in elevating social dialogue long after it was first conceived. Yes, a little over a year from now when An African Menagerie begins its museum tour, I can already see groups of Millennials posing in front of it, having selfies taken, and then posting the photographs on social media.

That isn’t a bad thing; it’s a great thing, for it’s an opportunity to ignite awareness about the plight of animals that, far from existing on the other side of Earth, are, in this day and age, really only a half day’s journey away from our front doors.

Today, humanity’s relationship to the natural world is disjointed and out of sync. We are currently at the front end of the sixth major species extinction episode though in Jarvi’s mind, An African Menagerie is intended to serve as a rallying cry. Its import will only grow as time goes on.

In spirit, Jarvi is indistinguishable from the 19thcentury Romantics who ventured into the American West chronicling the slaughter of wildlife—not the actual destruction itself, but illuminating the consequences. The artwork of those forerunners, from Audubon to Bierstadt, awakened a nation, leading to some of the most progressive conservation initiatives in the history of the world. The visionaries of our time, people ranging from E.O. Wilson to Jane Goodall say the same kind of action is needed to save the iconic species of Africa from plunder and habitat loss.

Just as the old masters explored religious themes which dominated in their times, just as muralist Diego Rivera explored issues of inequality in his day, Jarvi as an artist is speaking to one of the most important modern issues of our time—the environment—and he’s tackling it using an engaging approach. In his hands, wildlife art isn’t passe; it’s avant garde, humbling, magnetic, chastening, unifying, and accessible.

“What we do now will affect the kind of world our children and grandchildren inherit. I hope An African Menagerie will raise awareness. If these paintings can remind people what’s at stake, I’ll be happy,” Jarvi says.

My friend, the late and legendary David Brower recognized how fine art photography can make visible those things affecting our survival that need illumination. Combining art and conservation was for Brower a no-brainer.

When An African Menagerie commences its national tour in 2017, view it if you can. As you stand before the myriad manifestations of evolution, take a moment to reflect how the canvas would appear had you just landed on Mars. You’d be staring at a blank canvas. Just a single species, of the kind appearing in An African Menagerie would be a cosmic miracle.

The works featured above by Brian Jarvi are preliminary studies for the upcoming piece An African Menagerie, which will open October 1, 2017 at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Fort Hayes State University, Kansas. Brian Jarvi, b.1956, is a graduate of Floodwood High School, Floodwood, Minn. Brian has been a professional artist since 1985. Jarvi is a Signature Member of the Society of Animal Artists.

Todd Wilkinson lives in Bozeman, Montana and is a correspondent for National Geographic, The Christian Science Monitor and dozens of other major publications with assignments that have taken him around the globe. He also is author of several critically-acclaimed books, including the recent award-winning volume Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone (only available at mangelsen.com/grizzly) featuring 150 dramatic images by noted American nature photographer Thomas D. Mangelsen. He also wrote, in 2013, Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet.

Todd Wilkinson lives in Bozeman, Montana and is a correspondent for National Geographic, The Christian Science Monitor and dozens of other major publications with assignments that have taken him around the globe. He also is author of several critically-acclaimed books, including the recent award-winning volume Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone (only available at mangelsen.com/grizzly) featuring 150 dramatic images by noted American nature photographer Thomas D. Mangelsen. He also wrote, in 2013, Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet.

This post is part of the MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems and contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the new space.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org.

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/wildlife-art-rallying-cry/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.