David Wagner shares an excerpt from his introduction to the soon-to-be published book:

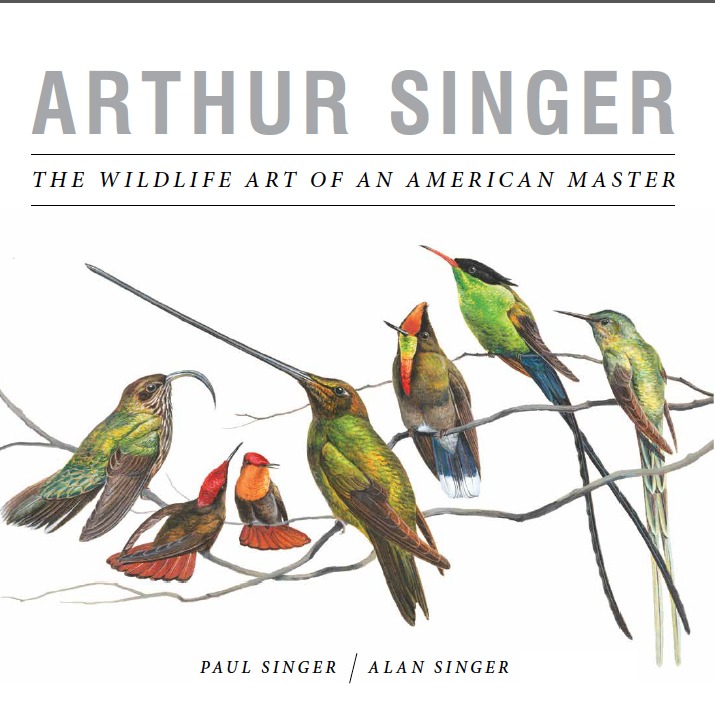

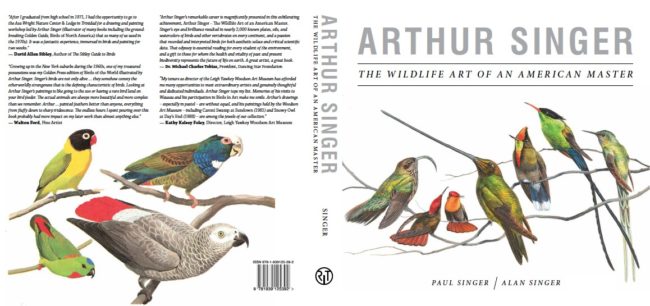

Arthur Singer: The Wildlife Art of an American Master

Authors: Sons, Paul Singer, Alan Singer

Layout and Design: Paul Singer

Introduction: David J. Wagner, Ph.D.

Publisher: Rochester Institute of Technology Press

Release Date: Late May/Early June 2017

Introduction Excerpt

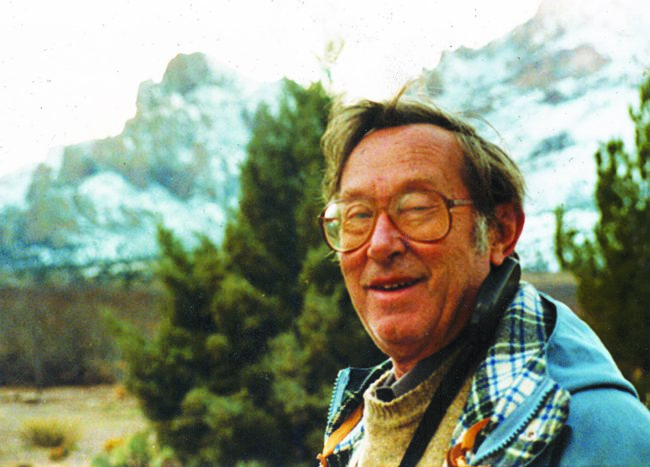

I am old enough to have professionally known Arthur Singer during his lifetime, and, though that was long ago, young enough to still remember him. I first met Arthur Singer in 1977, when he attended the opening reception of a group exhibition by leading artists who focused on bird subject matter. At the time, Arthur was 60, I was 25. Today, I remember Arthur Singer as an artist whose strongest works displayed the subtlest of tonalities and a beauty of patterned repetition, and as an artist situated squarely in mid-twentieth-century aesthetics, enterprise, and ideology when it comes to the art of natural history.

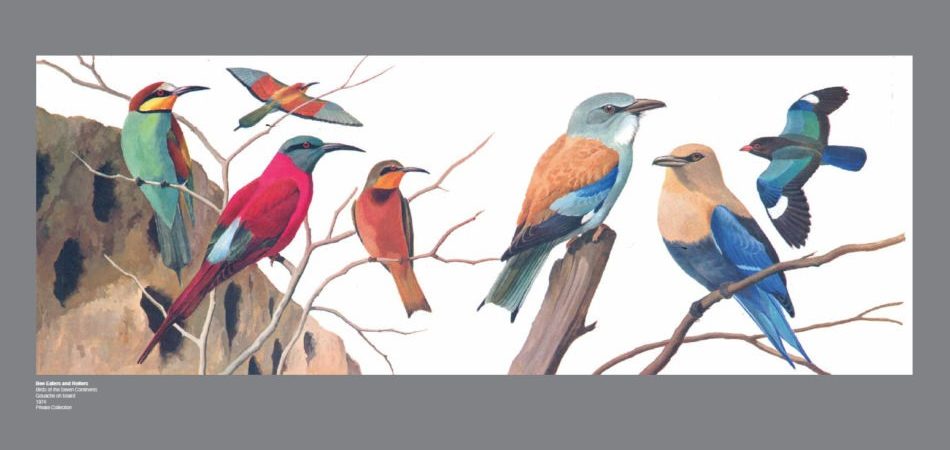

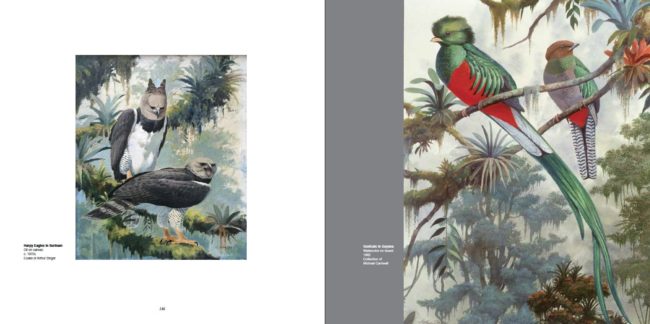

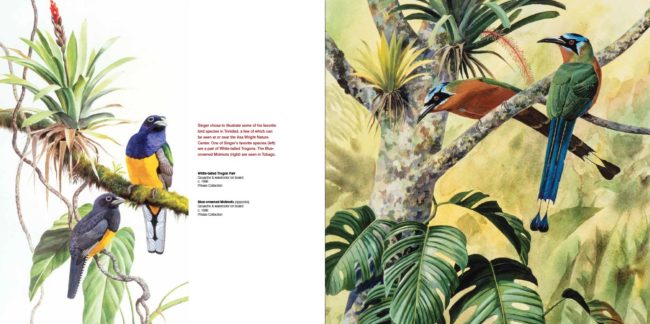

“Arthur Singer is along with Roger Tory Peterson one of America’s preeminent illustrators of bird life using the medium of paint rather than photography. This new volume, Arthur Singer: the Wildlife Art of an American Master, brings together many of Singer’s watercolors and paintings, some meant as salable individual easel works, others as samples of his various book illustrations, including the magnificent series of US postage stamps with birds, some as wildlife guides with deliberately exaggerated field marks, and then some of the most intriguing portraits of birds in groups. I find these groupings some of the most engaging works of this acknowledged painting genius.

His Red Headed Woodpeckers are singled out on an empty background only to display them in a family arrangement with a slight but revealing narrative about their interactions. Critics have pointed to some artists’ ability to capture what might be called the “inner consciousness” of avian subjects, but Singer depicts this trio of birds in a slight story line—male, female, chick—in the act of feeding and protecting their young from unseen but obvious threats. They are on guard, wary, and keep the youngster nearly hidden in the broken birch trunk, other evidence of nature’s risky challenges. This does not anthropomorphize the woodpeckers, but rather shows us what they must endure and negotiate as birds trying to survive.

This sort of narrative focus, as subtle as it is in Singer’s illustrations, was the older way of creating multi-figure displays and dioramas in places like Natural History Museums that told a story and enabled viewers to unwind that story and engage with the animals, often a variety of them in a particular landscape. This is what a painter of animals can accomplish even as he or she highlights and emphasizes features that enable easier identification.

We might think that photography provides the clearest picture of the animal in question, here birds, but this is based on a false notion that photographic realism is synonymous with reality itself. In fact deciphering a photograph is a cultural phenomenon learned and practiced until we can make sense of the image in front of us. It’s flat, square, smallish, usually over-colored, often shiny because of direct light and telescopic focusing. And the automatically captured minute details can distract as much as reveal the nature of the animal in question. I personally find myself going back and forth between painted and photographed birds in field guides in order to identify the bird, but also to the painted versions to understand its nature and in some way intuit its behavior as part of that identification and my relation to the critter in front of me.

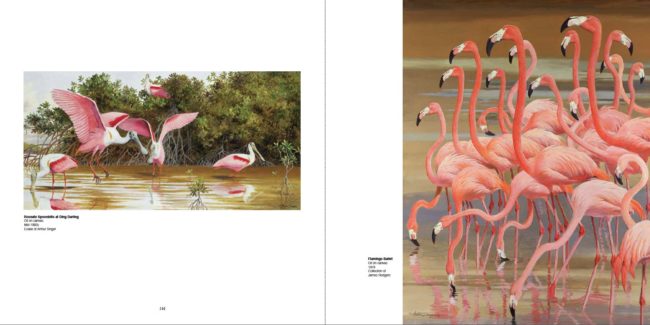

Singer’s grouping of a heron and five egrets lets us see the white egrets in different views, postures, and behaviors, preening, fishing, hunching down, while the two large ones look one way and the other, almost mirror images of each other, keep a close watch for trouble. The red-necked and brown-bodied heron is tolerated nearby, a sign of compatibility, as well as what to look for in the field search for either species—they might be found together. The background here is a sheltering mangrove, with two birds out in the open water, almost protected by the wary duo. The simple ‘story’ here is worth deciphering.

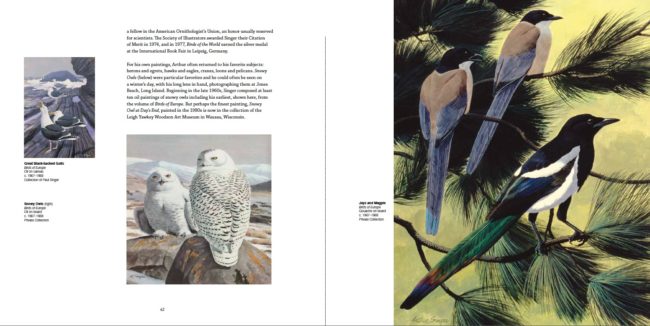

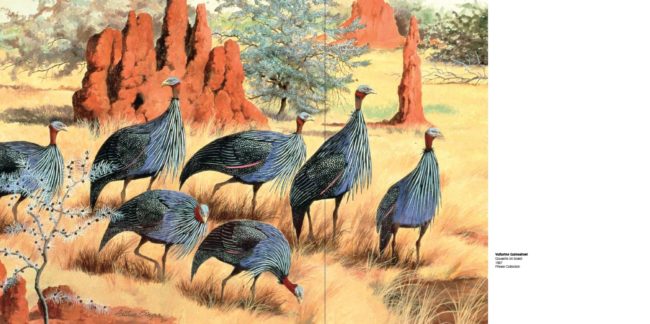

Singer goes wild with other massive groupings, almost showing off his painterly and structural skills—Crowned Cranes, and Scarlet Ibis, with the Ibis seeming to disturb the egret in the other painting from its sheltering trees. Then there are birds that look directly at us, less caught in the frame of a photograph but more inquiring about us. The Snowy and Great Gray owls are wondering why we stare.

Singer’s vision can encompass fine art, decoration, illustration and a look into the life of the bird.”Robert Louis Chianese, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus of English at California State University, Northridge, a 1979 Mitchell Prize Laureate in Sustainability, and Past President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Pacific Division

Arthur Singer (1917-1990) enrolled at the Cooper Union Art School in 1935 and graduated in 1939. Singer remained in art school through the Depression, only to have World War II stymie his career… but only briefly and in a way that contributed to his artistic development: in the army he spent 3½ years designing camouflage for tanks, trucks, and other field equipment for the military campaign in North Africa.[1]

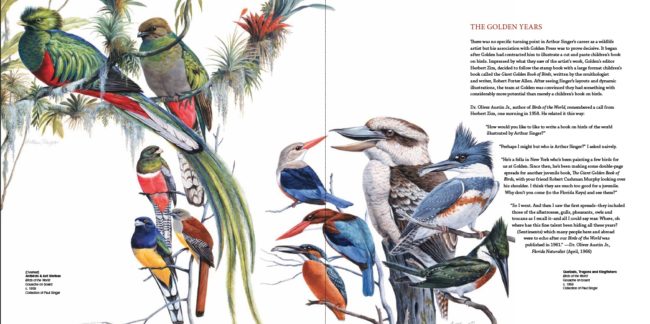

After the war, Arthur Singer returned to New York to work as an art director in a commercial advertising firm where he’d worked after graduation before the war, and briefly to Cooper Union to teach. In the early 1950s, he started doing free-lance work, including illustrations for nature articles in Sports Illustrated. His first big break in bird illustration came when World Book approached him after bird artist, Don Eckelberry turned down an assignment due to competing commitments to update its section on ornithology in the encyclopedia. This led to a commission to illustrate Birds of the World, published by Golden Books that came out in 1961 and sold in the hundreds of thousands. A bibliography of other books illustrated by Arthur Singer followed including Birds of North America published by Golden (the first real challenge to the Peterson field guide), as well as others including Birds of Europe published by Hamlyn in 1968, all of which drove Arthur to work twelve- to thirteen-hour days to produce countless illustrations through the turbulent sixties and into the 1970s.

“I first read Birds of the World illustrated by Arthur Singer at age 8 in Sri Lanka. I saved my pocket money for one year to purchase it, it was my very first bird book. It so inspired me and directly affected my attention to details and devotion to ornithological art.”

Gamini Ratnavira

Artist, Illustrator, and Naturalist

Like Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1874-1927), Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), and others at the top end of the century’s bird artist hierarchy, Arthur Singer provided content to a burgeoning publishing industry hungry for quality illustrations for a print culture booming with commodities such as magazines, a range of books from tiny scientific field guides to large juvenile picture books and encyclopedias, and collector prints, stamps, and plates.[2]

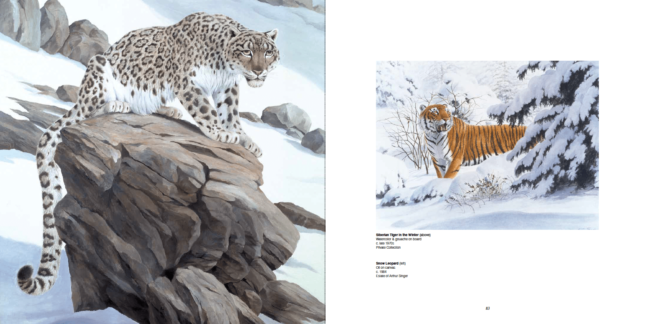

Arthur Singer’s illustrations contributed immensely to public education and enjoyment of the natural world at a time when the environmental movement would reach its zenith. His concern for the environment was both shaped and fulfilled by public and private conservation initiatives, not the least of which was major legislation such as the Endangered Species Act.

“Arthur Singer’s remarkable career is magnificently presented in this exhilarating achievement, Arthur Singer – The Wildlife Art of an American Master. Singer’s eye and brilliance resulted in nearly 2,000 known plates, oils, and watercolors of birds and other vertebrates on every continent, and a passion that recorded and interpreted birds for both aesthetic solace and critical scientific data.

That odyssey is essential reading for every student of the environment, and a gift to those for whom the health and vitality of past and present biodiversity represents the future of life on earth. A great artist, a great book.”

Michael Charles Tobias, Ph.D.

President, Dancing Star Foundation

Because Arthur Singer’s art differed from that of predecessors like Fuertes and Peterson, and from many of those in the next generation, he was able to distinguish himself as an individual artist with a signature style. Whereas as the crop of younger artists coming out of commercial illustration were practicing a new, photo-realist (some would say feather-counting) aesthetic, Singer took a more classical, old-school approach, relying instead on a palette of muted colors and soft, fluid brushwork, but still imbued his work with a modern sense of design. As one art critic wrote, “His subtle instinctive often mute color harmonies are unmistakable. But one is uniquely conscious of an overall design in his carefully thought out compositions—a dead giveaway of his early graphic design experience.”[3]

When asked if he worked differently when painting on assignment versus for the fun of it, Arthur answered, “On an assignment, I may make many careful progressive drawings before arriving at the final concept. But my watercolor landscapes may have no wildlife in the scene, and I enjoy the luxury and risk of the happy accidents that are the special delight of that medium.”[4]

My personal feeling about the easel paintings that Arthur Singer submitted for museum exhibitions is that they gave the impression of ease, much like a great performance by a virtuoso musician who makes his or her technique look easy to the point of being imperceptible compared to the beauty of the moment.[5] I think it is fair to say the same thing about the art of Arthur Singer.

David J. Wagner, Ph.D.

Author, American Wildlife Art

Chief Curator, David J. Wagner, L.L.C.

Tour Director, Society of Animal Artists

All images above are from Arthur Singer: The Wildlife Art of an American Master and are used here with permission. Additional images can be viewed below:

[1] Abbott Thayer (1849–1921), mentor of Louis Agassiz Fuertes, literally invented camouflage art in service of World War I.

[2] David J. Wagner, “SLEWAPS: Signed Limited Edition Wildlife Art Photolithographs” (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, published by University Microfilms International Dissertation Information Service, 1999).

[3] George Magnan, “Arthur Singer: In the Path of Audubon,” Today’s Art and Graphics 29, no. 8, (August 1981).

[4] Ibid.

[5] A metaphor that I believe Arthur Singer would have appreciated, since he was a real jazz aficionado.

This post is part of the MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems and contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the space.

MAHB Blog:https://mahb.stanford.edu/creative-expressions/arthur-singer/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.