This blog is the first in the Environmental Impact II series produced by David Wagner.

Humanity is no stranger to crisis, either self-inflicted or by natural planetary fates. How our species has managed its position on earth reflects the best and worst of who we are, from our desperate origins as tribal survivors, through our spectacular evolutions of technology and cultures. We have been wagers of war and purveyors of peace, stewards of and barbaric destroyers of the ecology that has given us our very existence.

Among the countless developments of human creative instincts, the making of what we call Art stands at the threshold of our historical presence, as the signal event of our becoming identifiably human. The unique place that art-making holds in our story is its power to reflect and consider collective experience, whether in symbolic forms rooted in a universal abstract language, or the captivating narratives that appeared on cave walls beginning over 40,000 years ago.

As I write this in 2019, in the span of one human lifetime we have seen the complete redefinition of Art and Culture, of information, and even what is defined as true and false. New technologies have provided unending streams of projected image and information. Cultural languages and forms that had evolved at a glacial pace for thousands of years have suddenly begun, as have the earth’s glaciers, to change before our very eyes.

For those of us old enough to have experienced even a 20th century upbringing, the contemplative pace of thought, and the allowance for the perspective that such a pace provides, has begun to feel like the domain of the ancients. And yet it is the dimension and wisdom available in this conscious domain that I believe may be our spiritual and physical salvation.

My own devotion to the practices of Painting and Drawing have, from the very beginning, offered a venue for the expression of my deepest concerns. It was the art of past masters that attracted my passionate interest in this, from the dramatic etchings and paintings of Francisco Goya, to German Expressionists grappling with 20th century social horrors, through the American master Jack Levine – all of these image makers devoted to paintings informed by moral outrage and concern. I felt their outrage was my own, and their passion my passion.

But there was also an eloquence of craft, and perceptual sensitivity that even now, as I recall these artists’ works, fill me with awe and wonder. It felt possible then, in the 1970’s when my career began, that an individual artist could contribute meaningfully to an ever evolving kaleidoscope of culture.

The protest movements in America that emerged as dominant themes as they focused attention on racial inequality, women’s rights and the Vietnam War annealed the senses of a generation longing for fairness and responsible action. Television and print reminded us daily of our reality, and demanded that we take a stand. Another early wave of awareness was what we now call the Environmental movement.

It has always seemed to me that in every aesthete there is a radical struggling to be free – and in every radical, an aesthete. Even as an Art student I could sense the differences in nature of my peers, some driven to engaging visually with current events, and others , perhaps of more refined sensibilities, reaching innovatively for metaphorical transcendence.

Although I may have longed for the purity and luminous beauty in my painting of an artist like Richard Diebenkorn, I realized early on that my voice was a very different one.

The Art of Painting has survived, at least through this date, in large part because of the passions of individual practitioners, and due to the range of individual style and concept available to be explored. After so much marketing and commercial promotion of Art stars, countless artists continue in constant pursuit of their dreams, with the ultimate ambition, at some primary level, to make the world a better place. And, amazingly, with or without success. Art has always offered to help us see ourselves and our world with fresh eyes and mind.

As the maker of paintings of often difficult subjects, such as open pit mines (“Tailings”, in the collection of the San Jose Museum and “On Earth As It Is In Heaven” in the Nevada Museum of Art’s permanent collection) it has been a major challenge to fuse that aesthetic longing mentioned earlier into a form that expresses emphatically an environmental disaster – questioning the very meaning of why one makes Art, and what value it can actually have.

It is the language of paint itself, of form and color that compelled me then and compels me now to make work with a message, less a matter of choice than of compulsion.

In David J. Wagner’s curated exhibit” Environmental Impact II”, “Holding Pond”, the third work in what became a trilogy of open pit mine paintings, the avenues for aesthetic beauty were called upon to present what appears to be a disaster of varying dimension – of a landscape carved into submission for mineral extraction, and a truck accident exploding on one of the gridded courses. There are paintings meant to be hung in a home to share a sense of beauty and celebration of visual life, and others, like “Holding Pond”, whose agenda is more to call a viewer to question what is seen, perhaps to think of the implications of a painting that occupies so much space with such a charged subject.

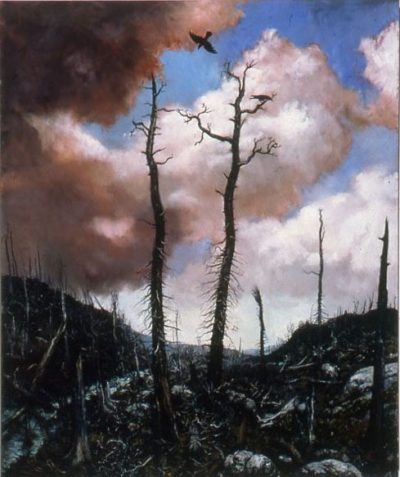

In “Two Ravens” / “Twa Corbies” the image of a pair of ravens cavorts effortlessly after a catastrophic forest fire. At the vanguard of the drying of the Western United States, California has been the victim of more than its share of serious wildfires. To consider the impact of climate change on our world is not new – as this painting was made in 1996 after severe fires in Yosemite National Park at the time. It serves as a sobering reminder of the fragility of our ecosystem, and the human presence in it in particular. As many post-apocalyptic paintings of burned landscapes, Two Ravens reflects a possibly impossible problem, yet points to some degree of natural resilience: blades of grass are beginning to emerge from the scorched forest floor, and birds still fly. We may be powerless to prevent every disaster, but with vigilance and thoughtful management, we might lessen our own contributions to catastrophe.

The secondary title of this work, “Twa Corbies” is the title of the old English poem in which a pair of Ravens, rather shockingly, discuss their daily meal – in this case a newly slain knight. In its last stanza, a haunting reflection on fate and eternity resound:

Mony a one for him makes mane,

But nane sall ken where he is gane;

O’er his white banes when they are bare

The wind sall blaw for evermair.

in modern English translation:

Many will mourn him

but no one will know where he has gone

Over his white bones, when they lie bare

The wind shall blow forevermore.

The animation, or human consciousness given the animal kingdom in this poem echoes in the realm of psychological magic in which I find much of the shape of my own thinking. This identification with all of life on earth as kin could be said to be an uninterrupted thread of human thought since our beginnings, and the source of powerful concern for the environment even now.

In the piece “The Great Piece Of Turf”, from 2008, I found the sod farms of California’s Sacramento Delta the source of connection with Albrecht Dürer’s watercolor of that name.

If Dürer occupied the dawning awareness of scientific and spiritual awakening of the early 16th century in his lovingly observed and rendered study, I felt that the modern viewer needed to see the engineered turf of this roll of instant lawn to contemplate and measure the distance we have come. It has been a move from the sublime and natural to the managed and often suppressed. This giant roll stares at us like an inert cyclops, awaiting transport.

As artists living and working in a world troubled by environmental challenges fought in courts of both legal and public opinion, it is in the unique domain of contemplation in a museum setting that ideas invested can yield their precious return. The value of a moment’s connection with another’s deep concerns, whether overt or oblique is the eternal value that Art has served in our lives from our beginnings.

It is the unique value of this collection of important works by artists of many media that these perspectives are allowed to build into a critical mass. When viewed together, they provide a new definition of how Modern Art can still contribute to the essential dialogue that seeks the preservation of our planet.

David J. Wagner, the force behind this venture, must be thanked for making such an important opportunity available to the museum going public. Artwork captions available at the official website.

Born in Santa Monica, California, in 1952, Chester Arnold was raised and educated in Germany, experience which significantly influenced his intellectual and aesthetic perspectives. The rich, dark and mysterious texture of European Art and History provided an indelible frame of reference for all that has followed. He began serious studies in painting and drawing in the Museums of Munich while still in high school, and upon returning to California attended the College of Marin in Kentfield, and the San Francisco Art Institute, from which he received his MFA in 1988. Exhibiting professionally since the mid-1980!s, Arnold work reflects a deep fascination with the natural world as well as the human condition: his paintings carry the craftsmanly regard of previous centuries in their passionate and moody narratives, while often tackling larger environmental and political issues . His work can be found in Public and private collections nationally, and has enjoyed a recent retrospective exhibit (2010) at the Nevada Museum of Art. A major solo touring exhibition surrounding the theme of human accumulations in his work is scheduled for a 2013 opening at the Katzen Art Center in Washington , D.C.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.