Growing up, three bothersome younger sisters drove me to seek beauty, knowledge, solace, fun, and wonder in the big woods surrounding our home. This was in a rapidly suburbanizing area just east of Seattle. I remember, at 14, crouching by an overgrown ditch along a busy road, watching a foot-long trout, motionless in the clear water, occasionally flicking out to catch an insect. Even during those early explorations, I remember feeling the enormity of life and my small place in it.

Then came the bulldozers and construction. The ditch disappeared. I doubt if anyone else had a clue about the community of creatures that was destroyed. Most called it “development” but I saw it as a kind of un-development. I felt tremendously sad and have continued to feel this sadness the last 30 years as this sort of thing happens again and again. The feeling keeps following me as it follows many of us as we sift through the losses.

This feeling of awe and wonder as well as sadness has shaped my life’s work. I became a biologist and worked on various conservation advocacy projects, which exhausted me. I also worked for a long time as an environmental regulator, which, sometimes to my chagrin, was a profession geared toward asking, “How can we find a path through the regulations for this project go ahead?”

My heart remained absorbed with the beauty of the world. When I look at a bird, feel the wind, or even gaze at my own hand, I am enthralled. I wondered: how could I inspire this feeling in others?

I wondered: how could

I inspire this feeling

in others?

Now, as a full time artist, I limit myself to a single medium. Any number of natural forms can foster appreciation for the natural world. I chose to use a rather unusual form: feathers. Ever since the head bird-keeper let me pick up pheasant and flamingo feathers at the zoo when I was twelve, I’ve seen feathers as reminders that I share the world with other creatures. Birds grow them, use them, and shed them. Yet when we find them, they have kept some of the essential qualities of the birds they came from like hints of flight, warmth, and beauty.

We have used feathers as symbols for millennia, everywhere on Earth. Feathers, to us, mean flight, transcendence, bridges between worlds, and escape. They are in our dreams. They are full of metaphor. As humans, we crave meaning. We find it through art and science, through religion, culture, myth, and our own experiences and imaginations.

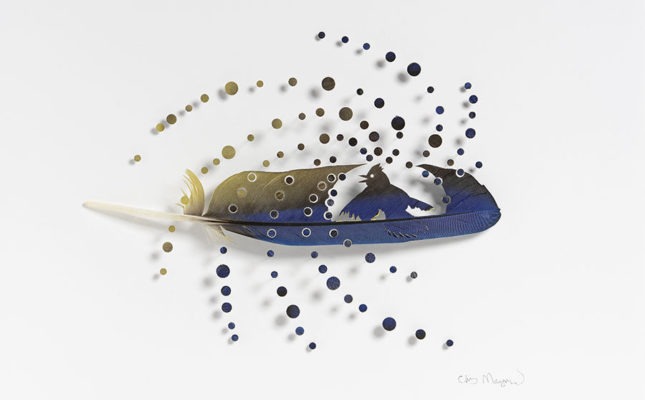

I sometimes blink, finding that I have been holding a feather and staring at it for the last half hour. I’ve been marveling at its lightness, wondering where it has been, and thinking, “How did this feather serve to keep the bird warm and dry, or help it to fly?” I might drop the feather to see it swirl, spin, or flutter to the ground. I find myself in the middle of three spaces of perception: wonder and awe at the form; a small sense of connection to the feather’s original owner; and the desire for creative construction, with the accompanying thought, “How can I manipulate this into elegant, compelling, and meaningful art that will make people stop and wonder?” I view each individual feather as a small bit of perfection, a structure that art cannot enhance. Even so, I cut bird shapes out of feathers to augment the meanings.

Part of me cries out

for gentleness where

beauty and wonder

have the upper hand.

It is feathers’ forms that draw me in. Certainly, feathers can have lovely colors and varied, interesting patterns. But the shapes and complex structures of the feathers are what makes them unique in the animal world. A museum curator recently told me that they were considering excluding my work from a museum tour around the United States. When I asked why, she said that the feathers were too delicate so she feared they would be damaged. This is a common misperception. We confuse lightness with delicacy. Feathers are made of protein, keratin. It is the same material our fingernails and a bird’s claws and beak are made of. They are made to be tough. At the same time, feathers don’t weigh much. They are light enough for a bird to fly at freeway speeds. They protect a bird for an entire year before they’re molted. They are a marvel of structural engineering.

The shapes of feathers drive my art. To honor feathers and the birds they came from, I don’t flatten them to a background but instead, keep their gentle curves by setting them apart from their background. Each flight feather curves a bit to form an airfoil. Each body feather, say of a duck, curves front to back and a bit from side to side to fit the bird’s body, like shingles covering a house’s roof. The body feathers’ curved shape also lets birds more fully expand or contract the feathers to provide less or more warmth. They fit together perfectly, overlapping to let both air and water slide smoothly along.

These are some of the reasons I find feathers alluring. It is a curious phenomenon: limiting oneself to a single focus can open up an enormous world of awe and exploration. So in my art, I find myself cutting and designing each piece, striving to capture an essence of a bird or what they do, like fly.

Life is harsh. We are born to die. To live, we kill things to eat. Creatures and habitats perish so we can have things, get where we are going, and pursue our many dreams. Part of me cries out for gentleness where beauty and wonder have the upper hand. Feathers do this for me. They serve their functions while gracing the bodies of the birds and are gently let go when a bird sheds. Yet they keep their form, complexity, and beauty. They are gifts from the birds.

Mr. Maynard spent his youth in the mountains and in the rain forests on the Quinault reservation. He would lie in the forest moss looking at birds in the tall trees. Since feathers represent flight, transformation, and a bridge between our present lives and our dreams, Mr. Maynard is grateful that his work with feathers has hit a soft-spot in the hearts of many people and cultures. His work is in private collections and featured in print in the US, Asia, Europe, and Australia. Mr. Maynard’s recent book, Feathers Form and Function highlights his art while informing about feathers. Mr. Maynard is a Member of The Society of Animal Artists. You can find more of his work here.

Mr. Maynard spent his youth in the mountains and in the rain forests on the Quinault reservation. He would lie in the forest moss looking at birds in the tall trees. Since feathers represent flight, transformation, and a bridge between our present lives and our dreams, Mr. Maynard is grateful that his work with feathers has hit a soft-spot in the hearts of many people and cultures. His work is in private collections and featured in print in the US, Asia, Europe, and Australia. Mr. Maynard’s recent book, Feathers Form and Function highlights his art while informing about feathers. Mr. Maynard is a Member of The Society of Animal Artists. You can find more of his work here.

This post is part of the MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems and contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the new space.

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/feathers-alluring/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.