David Wagner’s exhibition Environmental Impact represents a new level of broad yet focused appreciation for the sheer power, promise, and impact of art on the wisdom and sensibilities of current environmental crises. And crises they are. The myriad of artists, media and subject matter encompassed in the exhibition combine to convey a remarkable testimony to the urgency, persuasiveness and abundance of insights, perspectives, and power of art. Environmental Impact is packed not with empty mantras to a better state of being for the planet and all that dwell therein, or a blind and grasping homage to the beauty of life itself, but with deeply personal statements that range from deeply personal epiphanies to thoroughgoing activist expressionism: from figurative paroxysm to surreal data-crunching.

Viewers of Environmental Impact will experience the beauty, the turmoil, the levels of ambiguity and mixed message, but may also feel unexpected pangs of hope, even pragmatic responses to environmental concern and outright disaster.

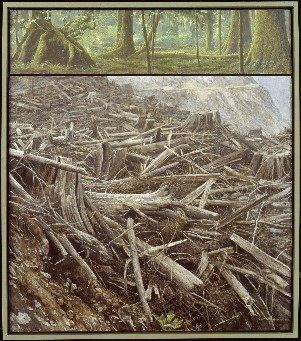

© Robert Bateman, Currently on display in Environmental Impact

Take one clear example that serves as a fitting emblem for the exhibition: the lead painting, by famed Canadian artist Robert Bateman, entitled Carmanah Contrast. The Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park in British Columbia has been much celebrated for its huge Sitka spruce, one of which is over a thousand years old and 314 feet high, amid a misty coast range of temperate rainforest like luxuriance. This park was created as recently as 1990, following outpourings of protests by locals over clear-cutting that had been occurring in the area for years. Bateman’s painting shows both sides of the story: the Creation, and human desecration.

In similar veins, Pieter Brueghel showed, in his The Gloomy Day and Hunters in the Snow (both painted in 1565) barren wintry trees populated by ravens, hunters and their dogs stalking game below, stormy peaks, frozen congeries of the human presence, suggesting a tenebrous looming angst symptomatic of our species’ presence in all directions. But at least the trees remained standing. Brueghel was likely unaware of the vast stretches of forests that had already been cleared throughout most of England and Europe’s lowlands, from Portugal to what is, today, Belarus.

Brueghel, in his own manner, was an activist, focusing upon human despair and disruption on so many levels. Whereas his eldest son, the Velvet Brueghel preferred to concentrate on magnificent renditions of paradise, Adam and Eve, of Noah’s Arc and perfect flower arrangements. It was this latter nostalgic evocation of Arcadia’s Golden Age that won over most artists of landscape throughout time.

That tradition goes back as far as documented art itself to the earliest known records of Paleolithic aesthetic sensibility at places like Lascaux and La grotte Cauvet Pont d’Arc, discovered in 1994, with over 400 animal depictions; or the 5,000+ cave images recently found at 11 sites throughout northeastern Mexico near Ciudad Victoria; to Mesolithic images of animal life in regions where the rain curtain would subsequently shift, exposing stark yet revealing petroglyphs in desert canyons that joined with later Egyptian and Greco-Roman frescoes to suggest an incipient grasp of the power of nature over human consciousness.

This power – humanity’s need and capacity, that is, to celebrate and revere nature —may well be the very key to humanity’s survival, if not the key to the endowment and pertinacity of the rest of those species and populations that cohabit the planet with us.

We may, as E. O. Wilson in his 2012 book The Social Conquest of Earth intimated, have overwhelmed most other life forms (perhaps as a negative consequence of the enormous impact of our ancestor’s transition to at least partial meat eating – hypocarnivorism – or one may so adduce) but our artistic reveries have only escalated in the wake of our seeming disassociation from the world of nature to which we were once so much more intimately attuned.

A 2012 Earth Policy Release by Janet Larsen Meat Consumption in China Now Double That in the United States shows how the Mandarin symbol in China for “home” is articulated as a pig under a roof.[1] Today, that pig is being slaughtered for human consumption in factory farms with more pigs killed in China than any where else in the world.[2]

Art, however, has only ascended by its power to heal and to save against the backdrop of such animal rights and environmental pain and impact. In the hands of great artists, art has been an agent of ecological consciousness raising and transformation. Classic examples include the seminal The Vision of Saint Eustace, c.1440 by Antonio Pisano (Pisanello) in London’s National Gallery; and Dutch Paulus Potter who, at the age of 22 painted Punishment of a Hunter now in the Hermitage. Other remarkable examples include British photographer John Bulmer’s 1963 image of a man and two dogs looking out over a grotesquely polluted city in View Over The Potteries, Stoke on Trent; disturbing photographs by Sebastião Salgado of famine in Africa and oppression in Brazilian mines reminiscent of Charles Dickens’ novel, Bleak House; and Nigel Brown whose disturbing, transformative work treats, among other things, the impact of British colonization – beginning with Captain Cook – on Brown’s home country of New Zealand, as particularly figured in Brown’s famed, magnificent stained glass project for the Auckland Cathedral (Parnell Street, 1998).[3]

Other environmental art clearly impacts in ways least traveled by, as in the case of one of the world’s earliest signed sand gardens, that of the 15th century Ryoanji Zen Temple in Kyoto, a quiet scene of international solace and meditation in a city that had seen one of the most bloody civil wars on record – the Onin (1467–1477). Japanese connoisseurs of tea, flower arrangements and landscape art did not so much as fight back with their aesthetics as supersede the warfare with an attitude, an orientation to life that today most assuredly prevails in the Greenbelt of “ten thousand garden monasteries” that is the global divining rod of Kyoto.

There are no formulas for how the aesthetic conscience is likely to operate, let alone perform miracles. The outcomes of any seemingly ideological contests are a case-by-case experiment in human behavior and perception. In the case of the nearly 11,000 currently known bird species, their beauty in our eyes (and in their own eyes, as beholders of one another – as can scientifically be surmised) has coincided with a mixed record, to be sure, of survival and extinctions, most usually at our hands.

The history of ornithological art –one of the greatest of natural history aesthetic media– originated in a frenzy of Latin-driven science based orientations, deriving from Aristotelian biology and culminating in such mammoth approaches to depicting the natural world as displayed by the great Buffon, Audubon, John Gould and J. G. Keulemans. It was the latter, prolific artist who supplied both Walter Lawry Buller (1838–1906) and Lord Walter Rothschild (1868–1937) magnificent paintings for their respective books Birds of New Zealand (1873) and Extinct Birds (1907) ushering in an era. An era in keeping with the transcendentalist calls for preservation by John Muir, President Abraham Lincoln, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt took the art and activism of John Muir to heart, embracing Muir’s unity of character, passion for writing, for fantastic metaphor, and re-invented America’s future, knowing that the paintings of a Bierstadt, the chromolithographs of a Moran, and the photographs of a Watkins must translate into more than mere imagination: these were real places demanding real action, if future generations were to have an opportunity to see what the Earth truly was.

Roosevelt, like the artists he admired – including photographer Edward Curtis, whose 20-volume The North American Indian with its 2200 remarkable images– reinvented the future for all of us, at a time when Curtis, and George Catlin before him, recognized the signs of “a vanishing race” and, like Audubon with the Passenger Pigeon, realized that, indeed, people, cultures and civilizations could go extinct just like birds, should we fail to act in time to save them.

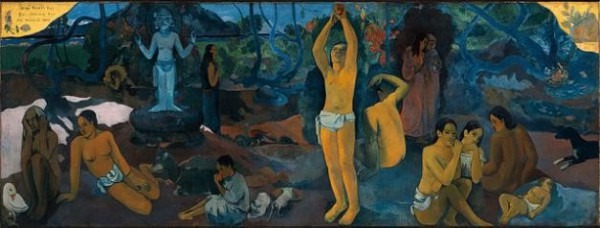

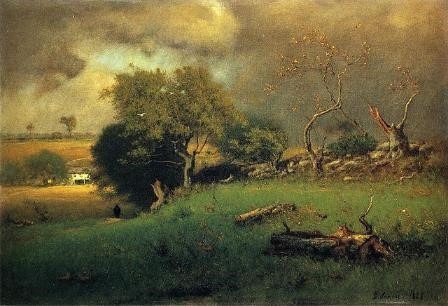

Sometimes the stakes were different than the protection of a big grove of trees in Mariposa, or a Yosemite Valley or Grand Canyon. Sometimes, it could be a pure and simple as a cow, painted by French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899); or a coming storm as figured in so many works by the brilliant Scottish/American Luminist George Inness (1825–1894) who saw the juxtapositions of sublime nature and the onrush of modernity across the horizon. Such technically assured empathy as that displayed throughout much of the Hudson River School, for example, on behalf of multi-tiered sentience all around us would come to dominate the emerging environmental rallying cries of the 20th and 21st centuries. E. O. Wilson’s aforementioned study actually commences with an examination of the subject matter and probable motivations goading one of Gauguin’s most salient, culminating meditations on human nature and the Tahitian landscape, his painting D’où Venons Nous/Que Sommes Nous/Où Allons Nous (Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?).

It was Inness, borrowing from a precedent in Thomas Cole (the forest stumps in many of his paintings) who frequently placed a clear and active smokestack within an otherwise perfectly tranquil natural scene. This is most disturbingly clear in Inness’ The Lackawanna Valley (c.1855) in The National Gallery in Washington D.C.

By 1923, the very love and admiration of artists spawned overpopulation by tourists in the Yosemite valley, air pollution, the obfuscation of indigenous populations (the Southern Miwok, for example), and other blights, while a million automobiles entered Yosemite National Park to the tune of a park superintendent declaring that Americans should be able to visit the parks in the standard to which they were accustomed (namely, in automobiles). This mob of adulation accounted for the carving of an automobile–sized hole through a giant redwood, an iconic (even celebrated statement at the time) of the conflict of the public’s love of nature, and the sad truth of the democratization of Eden.

By the late 1940s, sensitivity to natural scenery had been clearly revolutionized. National Geographic’s pictorial spread of the North Cascades’ sublimity, after a similar depiction of Yellowstone many decades before by nineteenth-century painter, Thomas Moran, would result in runaway public fanfare and a storm of the earliest so-called eco-tourism and picture postcards by photographers Edward Muybridge as to force the hand of Congress in their determination to protect over-crowded sites of world-heritage class stature. Whether overcrowding can be stopped in a world destined to add billions of more consumers hungry for wilderness remains one of the most troubling and unanswerable of conundrums for the artist and naturalist.

All of these conflicting attitudes and historic truths combine to inject countless ambiguities into the history of landscape art, and the environmental impact that has arisen in the historic and cumulative sensibility of protecting paradise, as it were. These are but a few among the many resonances of David Wagner’s exhibition, Environmental Impact.

From New Mexico to Israel, Wagner has sought out works of art that lend credence to the all-too real truth of environmental despoliation occurring worldwide. Read More…

1 Janet Larsen, Meat Consumption in China Now Double That in the United States, Earth Policy Institute, 24 April 2012.

2 Michael C Tobias, Animal Rights in China, Forbes, 2 November 2012.

3 Michael C Tobias, Nigel Brown: A New Zealand Original, Forbes, 10 April 2013.

Michael Charles Tobias, Ph.D. & Jane Gray Morrison President & Executive Vice President, Dancing Star Foundation 2012 © Dancing Star Foundation, dancingstarfoundation.org

This post is part of the newly launched MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems. Please contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the new space.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/reflecting-ecological-doom-resurrection/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.