Kathleen Velo and Michael Bogan have only recently teamed up through the 6&6 Collaboration, but they have wasted no time in getting their project moving forward. Forged by the Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers network (N-Gen, www.nextgensd.com), 6&6 is a collaboration between artists and scientists to explore the patterns and processes of the Sonoran Desert and Gulf of California. Velo explains, “We got a late start, because of different incidents and events that took place. We’re not rushing to catch up, we’re just flowing along and making sense of things as we go.” After an earlier collaboration didn’t work out due to diverging areas of interest, Velo and Bogan connected back in November. During their first meeting over coffee they discussed “if, and where, there were some natural connections” between their work, and found that a lot of their interests, and the scale they worked at, aligned very well. Bogan is an aquatic ecologist who researches how disturbances to ecosystems, such as wildfires, droughts, or mining spills, shape the types of species found in freshwater lakes and streams. Velo is a photographic artist who has been working with the topics of water and water flow for about seven years. Velo goes “directly into the source to create primarily underwater photograms that show some of the effects of the disturbances that Michael was talking about, to water sources.”

Velo and Bogan point to the commonalities in their work as clear assets to being able to dive into the collaboration. Bogan says, “Kathleen was already interested and working in water, the ideas of water flow, and further the ideas of water in a watershed or drainage basin. The idea of connected streams flowing together, different places across the landscape. That’s essentially the scales that I think at and work at for my research.” In addition to the commonalities in their areas of interest, Bogan and Velo have also found that their abilities to be flexible in the shaping of the project have been critical to its success so far. Bogan explains, “Both of us are able to have a lot of flexibility and adjust the ideas as we go to make them match even better. If I had some huge existing research project with a bunch of students working on it and a lot of collaborators, and then afterwards was trying to shoehorn in a fit with an artist, I think that would be a lot harder. Luckily, in this particular pairing, it’s a natural fit and both of us are at early enough stages from both the science perspective and the art perspective that we’ll be on a similar road to discovery for the next year or so as we work through the project.”

Since their first meeting they have reconnected a few times to revisit if they “both really had time to do this kind of involved collaboration, and to try to get some geographic sense of where it was going to go, and how the geography of the project would potentially facilitate it actually being a successful collaboration.” During those meetings Bogan says, “We started to get really excited about focusing on our local watershed, the Santa Cruz River, that flows through Tucson.” With the unusual amount of snow Tucson received early in the winter Bogan explains, “some of the streams in Tucson that are normally just dry, sandy river beds actually had beautiful, cold flowing water for six or seven weeks this winter. Tucson had a proper river for a little while.” Bogan and Velo took advantage of the flowing waterways, taking a few trips into the field together to look at aquatic species and to make underwater photograms –the photographic processing Velo specializes in.

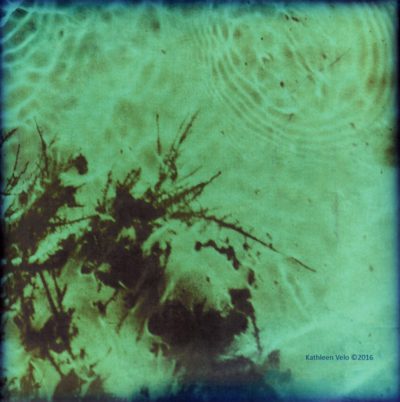

Velo creates photograms by going directly into the water. Velo explains, “I actually go into the water and put photographic paper underwater, at night, and then expose it to a light source, which captures an image of the water –what’s in the water, the movement of the water, the viscosity, silt, plants, insects, whatever happens to be there.” It’s a long process that takes many hands. “What I learned when I started working with this type of photography is it takes a community. It takes a lot people to make things happen. It’s very different, I think, than the typical stereotype of artists being alone in their studios and just creating whatever tends to come out of their heads.” A misconception Velo recognizes gets applied to scientists as well.

Recognizing they are still early in the process of forming their ideas, Velo and Bogan are playing around with combining the photograms with images of the aquatic life forms Bogan has collected. Velo is excited for the opportunity to explore the possibilities. One of the surprises from the project for Velo has been the artistic freedom it has granted her: “Just prior to becoming involved with 6&6, I had worked on this fairly major exhibition for the museum here, which consumed my life for a few years. I was feeling in a bit of a slump and this has really invigorated me and given me some inspiration to try different things and experiment with different processes.”

Though their overlapping interests have helped the collaboration move forward smoothly, Velo points out that it is the differences in their work, and the inherent differences in art and science that makes these collaborations valuable: “The collaboration brings two, totally different intellectual, psychological, emotional perspectives together. The artist and the scientist feed off each other. I think it offers opportunity for both partners to grow and to see things from a very different perspective… as we collaborate I’d like to think minds are being opened to different perspectives, different ways of looking at things, and it’s giving each of us the opportunity to expand our own thought process and our own creative approach to our discipline. And then, to carry that forward to communicate more effectively in a more diverse way about the work that we’re doing to the general public.”

Bogan agrees, and recognizes how collaborations like this can give scientists a much needed nudge to get out of ruts they may find themselves in: “I think it’s really valuable to step back a little bit from the normal way we process a landscape, or process biological patterns, and see those landscapes or those species or those patterns through a totally different lens. It’s really easy in science to get very focused, and very in a groove where you’re always looking at things the same way. Consistency is an important trait in science, but at some point you can get stuck in that and miss out –either on really interesting things that should get more scientific attention or just different ways of seeing the same thing. Looking at scientific facts, or biological systems, through an art lens can help a scientist shake the rut that they’re in –even if it’s a good rut, a productive rut.” Bogan, as “a cautious scientist”, isn’t ready to make any definitive statements about how the collaboration will affect his work, but is “fairly certain it will.”

They agree that the collaboration has been very fun and enjoyable so far (which might have something to do with their meeting place of choice which Bogan described as their favorite “video store, which also has a tap room and nice beer collection.” To which Velo clarified, “It’s a video pub.”) and they are excited to see where it leads them next.

This project is part of the 6&6 collaboration introduced at the end of April. You can find out more about 6&6 here. The MAHB will be featuring additional scientist-artist partnerships from the collaboration in the coming weeks.

The above post is through the MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems and contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the space.

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/creative-expressions/disturbances-flow/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.