How do you define happiness?

“A calm and modest life brings more happiness than the pursuit of success combined with constant restlessness” –Albert Einstein

Happiness may be the most common goal shared by humans. However, its definition comes in many shapes and colors.

In most modern cultures, the quest for happiness and sense of belonging is rooted in financial success. We believe that money and materialism define our place in society. Consider Adam Smith’s example of a linen shirt:

“A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessary of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably, though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-laborer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt, the want of which would be supposed to denote that disgraceful degree of poverty…”—Adam Smith 1723-1790

The shirt is not a necessity, but rather, it is a symbol of one’s place in society by means of material consumption.

People are wealthier then ever. The more money they have, the more they consume, which drives more wealth and even more consumption. This is the perfect recipe for a traditional growth-oriented economist. However, materialism has slowly—and unnoticeably—filled more gaps that create personal satisfaction. What’s more, consumption is so deeply embedded in society that breaking from common behaviors of consumption often results in scrutiny.

The culprit: Hedonic Adaptation.

Hedonic adaptation is the tendency of humans to return to a set level of happiness despite life’s ups and downs. In other words, their personal joys and sorrows fade with time. For example, the pleasure of buying a new item or the distress of a personal loss eventually return to an emotional baseline.

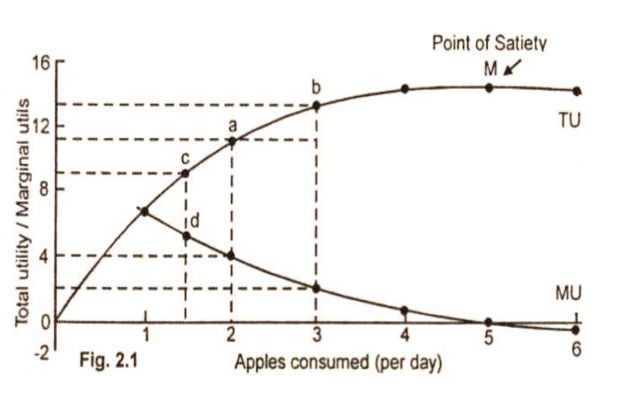

Marketers studying hedonic adaptation discovered a close relationship between consumer behavior and economics. They found that when a consumer uses more of a product or service, their level of satisfaction decreases with each use. For example, each time you drive your new car, you feel a little less satisfaction than the previous time your drove the car. This fading satisfaction is called “diminishing marginal utility”. Utility is “the basis on which the demand of an individual for a commodity depends upon,” (Jevons 1835–1882) and the sum of these utilities, is called total utility. Thus, as satisfaction (marginal utility) declines, satiety (total utility) increases until it eventually levels (see figure).

As the number of apples consumed per day increase, total utility per marginal unit increased until a point of satiety (M) was reached, after which total utility plateaued.

Marketers and economists have linked hedonic adaptation and diminishing marginal utility to measure product value and forecast revenue. I doubt most of them measure—or care about—the implications of social and mental health related to our restless search for human satisfaction through material goods. According to renowned British philosopher and author Kate Soper, consumer society has passed a critical point in which materialism is now actively detracting from human well-being (Tim Jackson 2009).

The question is how can we detach from today’s money-oriented habits that environmental experts know will affect the quality of life and prosperity of future generations? Fortunately, utility is subjective. And for the sake of our mental health and environment, utility depends on how we can teach ourselves to resist what marketing has successfully trained us to do.

Jordi Quoidbach and Elizabeth W. Dunn (2013) found that temporarily giving up a product or service may offer more happiness once it’s eventually acquired. By considering this theory with the intention to experience my own happiness, I’m encouraged to train myself to consume with a purpose rather than an impulse. With each purchase, I ask myself whether this particular product or service will improve my quality of life or make me a better person. If the answer is yes, for how long will it enhance my life (e.g., minutes, days, months, years).

I encourage everyone to delay impulsive purchases. You will often surprise yourself when realizing that your sense of need fades and amazingly helps you appreciate the joys you already have in life.

On the other hand, we cannot detach from our economic environment as we depend on many goods. However, we can truly be honest with ourselves, step back and think about what really makes us happy. Since materialism is hidden in every corner, by taking a deep search within, you may realize how financial well-being is erroneously at the core of our society. Learn how to experience real happiness by improving your health and fostering a sustainable environment for future generations.

You may then answer differently my opening question above:

How do you define happiness?

Oscar De Uriarte lives in Valle de Bravo, Mexico. His science background and business experience, have given him the tools to recognize the close relationship between population change, economic models and his beloved environment.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

References

- Quoidbach, Jordi & Dunn, Elizabeth. (2013). Give It Up A Strategy for Combating Hedonic Adaptation. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 4. 563-568. 10.1177/1948550612473489. Sonja Lyubomirsky, ???).

- Mosselmans, Bert, “William Stanley Jevons”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/william-jevons/>.

- http://economicsconcepts.com

- Jackson, Tim. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. London: Earthscan, 2009.