Life on Earth is largely organized by the rhythm of light and darkness. For billions of years, our planet’s rotation around the sun divided time into day and night. The Earth’s orbital journey and tilt around the axis determined the hours of daylight throughout the seasons. The moon’s monthly cycle provided the light at night, and weather conditions affected the more local variations. All ecological and evolutionary processes were played out against these constants.

Now, artificial lighting is a common feature of human settlements and infrastructure, perturbing the natural regulation of light and darkness. Economic and technological developments mean that artificial light increasingly encroaches on dark sanctuaries in space, time, and across wavelengths – from dusk to dawn, 365 days a year.

Many parts of the world are now so brightly lit that people cannot see the stars at night due to street lighting, advertising, lighting of commercial and residential buildings and sport venues. Moreover, the excessive use of artificial light – light pollution – can have seriously damaging effects on all biological life forms, from single cells to ecosystems. Research has shown that artificial light interferes with hunter-prey relationships, reproduction, circadian rhythm, nocturnal activities, feeding rates, migration patterns in birds and photosynthesis in plants. Other negative effects of light pollution include increased energy consumption from excessive lighting; interestingly, brighter lights do not necessarily improve safety. Unlike other forms of pollution, light pollution can more easily be reversed, for example by adopting sensible lighting techniques.

Having transgressed the safe operating space of several planetary boundaries and recognizing that life on Earth (as we know it) is in peril, requires widespread systems thinking: all is interconnected. No discipline is exempt from creating awareness about the consequences, the fact that we are to blame, and from the determination to forge a better path than the current one. We have every reason to radically rethink our beliefs, our worldviews, and our institutional, cultural and economic structures. The departure from business as usual often starts with education. Education has a fundamental role in preparing students for the challenges ahead, and in fostering understanding for our place in the world.

This newsletter invites you to explore your own relationship with light – a more complex issue than just black and white – and presents three interdisciplinary approaches to teaching sustainability from a humanities and social sciences perspective.

We start with Bill Davis, Associate Professor of Photography and Intermedia at the Gwen Frostic

School of Modern Art at Western Michigan University (WMU). Bill’s work intersects with teaching sustainability; his recent exhibition No Dark in Sight focuses on light pollution – a pressing but seldom recognized problem of modern civilization. According to Zsolt Bátori, it is the “strong tension between the perceptual and aesthetic experience of the compositional beauty of the photographs and the cognitive recognition of what Davis considers being dangerous or even harmful for our lives”. This artificial illumination of the night sky cuts short our connection with the natural world, and the aesthetic quality of the images forces us to consider the ethical dimension behind them. In asking what makes these images beautiful he also provides us with the answer: it’s the artificial transformation of the night, revealing what the human eye cannot see under natural conditions. There is, however, a price to pay: that which was destroyed by the artificial.

Thomas Tunstall, Ph.D., is Director of Research at the Institute of Economic Development, University of Texas and San Antonio (UTSA). Given global resource consumption patterns, he sees a highly interdisciplinary approach, paired with a systematic “Big History Framework”, as essential for teaching students – the future policy makers – how to articulate thoughtful scenarios for the future.

Wendy Petersen-Boring is an Associate Professor of History and Religious Studies at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon where she teaches pre-modern Western history, gender and sustainability issues. Her approach focuses on students’ existential experience of climate change, species loss and environmental injustice so we can create a new story of who we are.

We also incorporate student perspectives from these courses as we learn from the upcoming leaders how they perceive the challenges and their roles in the world, and by sharing what they gained from these courses.

Artist Bill Davis has worked on 6 continents. His project, No Dark in Sight, is funded to exhibit how artificial light is used to manage culture– as a dystopian condition rewriting our unfit relationship to darkness. Aware of our Anthropocene era, Davis exhibits empirical inquiry, sustainability, and human impact. Like artists before, he uses environmental science to express his humanity. Davinci relied on math, Michelangelo performed autopsies, and Turrell engineered temples for light. Trained to embrace light, Davis is not opposed to its artificial form, just focused on its counter-evolutionary connection to the biosphere. He now calls light a frenemy. When night looks like day, we have a problem. It’s unnatural. Davis photographs many sites meeting Bortle Dark-Sky scale ratings as recklessly over-lit nighttime space. Look no further than cities to find the unnatural light that redefines their night. No Dark in Sight essentially observes light trespass. Quality of light affects quality of life. Davis awakens us to darkness as a sovereign right because we are not alert to its absence as a corporeal threat. No Dark in Sight invites viewers to meditate on their relationship to light– as consumers and producers.

Oil and Water

Kalamazoo, Michigan

Human nature is staged against human hubris in “Oil and Water”… I set my tripod on the frozen asphalt and waited for someone or something to confess to this transgression against humanity. No one came forward. Sadly, I knew I was the judge, the victim, and the culprit…

“Oil and Water” shows a frozen pile of black and white sludge. (See lecture: 9:30). Not unlike a crime scene, it was hard to stomach. This bright peak cut a path of crystalized frost into the night sky above the parking lot it occupied– splitting the composition crosswise. The massive slope of the day’s leftovers towered over cars like Yosemite’s Half Dome over its valleys. Photographer William Henry Jackson’s 19th century spirit was afoot. I set my tripod on the frozen asphalt and waited for someone or something to confess to this transgression against humanity. No one came forward. Sadly, I knew I was the judge, the victim, and the culprit.

Human nature is staged against human hubris in “Oil and Water”. The two don’t mix. One is life giving; the other not. No two substances have a greater grip on our planet. One we desire, one we need. This image unfolds a disquieting scene of mixed sludge, which conflates compounds we need with those we don’t. We kill for both. If water is justice, fossil fuel is a crime. Less natural is the new normal.

Swarm

Portage, Michigan

“Swarm” is a hyperactive image, which conveys the nature of supply and demand. A close study illustrates the complicated relationship between natural and unnatural worlds …The light assaulted my eyes but more greatly assaulted the confused moths. I was immersed in a grotesque site– questioning light and its relationship to life.

“Swarm” is a hyperactive image, which conveys the nature of supply and demand. A close study illustrates the complicated relationship between natural and unnatural worlds– more specifically in this image, moths dazed by artificial light. (See lecture: 14:15). As an indicator species for the state of biodiversity, moths are a key “supply-side” ingredient to the “demand-side” nutritional needs of bats, spiders, lizards, and birds. I witnessed frenetic moths dazed in a path created by artificial light used for an American flag. As I photographed this swarm, it looked like the violent and expressively painted canvases of Pollock and DeKooning. The light assaulted my eyes but more greatly assaulted the confused moths. I was immersed in a grotesque site– questioning light and its relationship to life.

Abstract Expressionism confronts us in ways that challenge the preconceived or pedestrian definitions of art. It alienates us from reason, immerses us in chaos, and makes the natural world unclear. Much like watching insects negotiate for space in flag lighting.

This image analogizes a culture’s desire to prioritize self-service over self-preservation– like a selfish canary painted into an abstract coal mine.

Canvas of Light

Madrid, Spain

The uplighting in this photo reminds me to recall the paintings of Diego Velasquez… Canvas of Light appeared assaulted by light and engulfed in flame. As if light below had demonized the cloth. Is the night sky not pillaged in the same way– with the afterglow of artificial light tarnishing a once more natural and golden age?

“Canvas of Light” surprises and disappoints. It reminds us that photography is a time capsule– made to convey the lived human experience. All photographs remind us to remember. The uplighting in this photo reminds me to recall the paintings of Diego Velasquez. It could have been a detail from Las Meninas or The Education of the Virgin. Velasquez embodied the Golden Age, which promoted empathy, equality, inquiry, and human dignity. I positioned my tripod behind Madrid’s Prado Museum where Velasquez paintings hung– hypnotized by lit canvas hanging from the roof. Standing at the heel of the museum that embraces the Golden Age, this canvas appeared assaulted by light and engulfed in flame. As if light below had demonized the cloth. Is the night sky not pillaged in the same way– with the afterglow of artificial light tarnishing a once more natural and golden age?

Following sunset I toured Madrid, Europe’s reputed brightest city at night– to discover how that reputation was earned. (See lecture: 36:10). I was excited to start my tour at The Prado; and later deflated to sink in the undertow of its artificial light. As gatekeeper to art, culture and the legacy of a gold-tinged era, The Prado had over-lit the community it purportedly served.

Unreal Estate

Kalamazoo, Michigan

Goya’s Saturn in which the god of time grotesquely devours his son…. only made his longevity and legacies less sustainable. “Unreal Estate” unnervingly depicts a mall being constructed to over-accommodate a Middle American community’s consumer desire… the autopsy of our planet will reveal the myth of a sole cannibal with nothing left to eat but itself.

“Unreal Estate” unnervingly depicts a mall being constructed to over-accommodate a Middle American community’s consumer desire. (See lecture: 8:35).

I looked through the autumn chill– stunned to watch sky swallow earth. This image prompts me to recall the mythology in Goya’s Saturn in which the god of time grotesquely devours his son. Yet “Unreal Estate” advances that metaphor– as if the night sky, unable to avoid its own trajectory, becomes the last cannibal standing– eating the buildings and itself. In trying to prevent his fateful doom, Saturn only made his longevity and legacies less sustainable. In trying to prevent the night from occurring, we only make the future for the natural world less secure and stable. In this modern telling, the mall structures are constructed of the same building blocks and composed in similar form– with one sprung from the other like a vulnerable son from a dominant father. I stood witness to a volatile and electric blanket of jaundiced orange skyglow envelop this family of cinder block and the immediate troposphere.

Can we summon the will to compose a better self-portrait? If not, the autopsy of our planet will reveal the myth of a sole cannibal with nothing left to eat but itself.

Free Light

Cincinnati, Ohio

“Free Light” is an abbreviated title for America’s most disturbing and inhumane chapter…I paused to consider what the North Star meant to the 100,000 slaves who secured their freedom…(Light pollution) could be discussed as a near dismantling of free will…

“Free Light” is an abbreviated title for America’s most disturbing and inhumane chapter. What started as an interest to photograph a lit Ferris wheel became a greater discovery. Behind the spinning disc was a remarkably illuminated reflection of 100,000 northerly lights dancing across the facade of The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. The glass seemed to melt the light. It was like seeing two Ferris wheels simultaneously: one imagined, the other real. (See lecture: 23:41).

Yet spinning wheels of light became secondary to the primary message staring me down– this site honors the legacy of free will; and it was like watching shooting stars. After I made the image, I paused to consider what the North Star meant to the 100,000 slaves who secured their freedom (and what light trespass may have done to imperil their journey). Light pollution, therefore, is more than a threat to public health and safety. It could be discussed as a near dismantling of free will– skewed by a few decades between the end of the railroad and beginning of artificial light. Be it not for a century of dark nights, freedom tells a different story.

Viva dark skies!

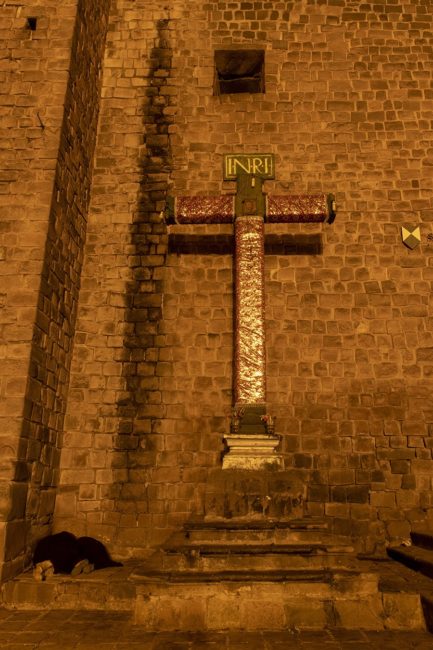

Sacred Light

Cusco, Peru

“Sacred Light” illustrates the multiple meanings of sacred sites… Like McDonald’s arches, the cross occupied a space between museums and cathedrals… Cusco’s Catholic Church collects rent from Starbucks, KFC, and McDonalds…. I was as astonished to find trespassing light that flushed Peruvians in a toxic haze.

“Sacred Light” illustrates the multiple meanings of sacred sites. A place for worship is also one for refuge; yet the area is bathed in second-hand light, like billowing smoke cast from a nearby thurible. I traversed Cusco’s Wajaypata to scout sacred sites. This meant exposure to the cross and its symbolism. Like McDonald’s arches, the cross occupied a space between museums and cathedrals.

“Sacred Light” prompts me to reflect on Christian artist Andre Serrano’s Piss Christ. He made the work to convey the conflict between commerce and Christianity, which was visibly evident in Peru. Cusco’s Catholic Church collects rent from Starbucks, KFC, and McDonalds. In this image I see mortality, disenfranchisement, power, faith, and despair. The yellow orange light cast by nearby merchants bathed the space in a ureativ glow. I was as astonished to find trespassing light that flushed Peruvians in a toxic haze.

A wrapped, once bare, cross towers above the huddled figures in vertical domination. I bowed my head in disbelief. The prayer position that would otherwise seem so clearly appropriate had lost all agency when I stood at the foot of an impotent symbol– bigger than but not in service of those asleep below.

Safe Space

Cincinnati Ohio Zoo, USA

Safe Space

The exhibit in this photo “Safe Space” is designed to protect captive wildlife. However, there were no signs of activity… Is naturally dark night sky not an endangered species? Is the biosphere not made unsafe by the light we produce?

The exhibit in this photo is designed to protect captive wildlife. However, there were no signs of activity in this barren, azure blue, and ominous “Safe Space”. Had its inhabitants been scared away by the red Exit sign or the hovering tungsten eye so reminiscent of Redon’s Cyclops? The dreamy enclosure echoed the surrealism of Tanguy, the solitude of Dali, and color fields of Rothko. Veins on fake trees looked like vascular hands on melting clocks. I could barely see my own reflection on the glass of the nocturnal house that separated me from the captive lives.

I think of unsafe spaces when seeking safe ones. This image conveys that need for safe spaces because of the hostile instability existing outside of them. Nocturnes can surely value that condition. Is naturally dark night sky not an endangered species? Is the biosphere not made unsafe by the light we produce? Can we find compromise?

Redon and Dali remind us that sleep fuels creativity. We depend on one to provide the other. Deep natural darkness, like secure safe space, is hard to find. This manufactured site was dreamlike, but its mere existence demonstrated the nightmares at play in our ecosystem.

What positive role does light play in our experience as human beings and how have we evolved to depend on light, sustainable or not? Hear more about Bill’s experience creating this art by listening to his No Dark In Sight lecture given at Western Michigan University.

Read and see more of Bill’s work in the MAHB Library.

University of Texas San Antonio Honors College Prepares Students for the Challenges Ahead

By Thomas Tunstall

How we think about sustainability is the point of Thomas Tunstall’s teaching. To truly educate a new generation of thinkers and problem solvers requires interdisciplinary education, moving the discussion to a more holistic approach. The answers to problems are not only this or that, they are sometimes this and that, or neither this nor that but another possibility altogether that remains to be examined.

Last year, the University of Texas at San Antonio Honors College freshmen inaugurated the first run at an introductory course entitled Tutorial I under the rubric of Energy. Other sections address themes such as Sustainability, Media and even Happiness.

The Honors Tutorial I is a required course for all Honors College matriculates. Instructors work with aspiring scholars on how to read, write and engage in popular intellectual discourse. As such, the approach is, by definition, highly interdisciplinary in nature. Students identify and evaluate sources of information, and develop a base of knowledge essential for engaging in public policy conversations.

Given the acrimonious rhetoric now common in public policy debates, it’s worth dissecting where those exchanges sometimes go off the rails. In many cases, issues are oversimplified – a hammer sees everything as a nail. Alternatively, sometimes experts enter the fray with such a narrow focus that the bigger picture gets lost in the exquisite detail. All too often, the debate merely descends into personal attack.

Honors College freshmen have excelled over their academic careers at specialized study in discrete courses: math, physical sciences, biology, selected portions of world history and the like. Rarely, however, are they tasked with bringing the pieces together as public policy discussions require. Their challenge then is to cultivate confidence by linking the individual disciplines with which they have become familiar to create meaningful, coherent and credible narratives.

The facility to discuss public policy issues in a lucid manner benefits from a unifying context to encourage those linkages. The framework employed in my class is a concept called Big History, which David Christian, among other scholars, has developed as a way to paint a very large canvas in broad strokes. In barely 300 pages, Christian lays out an account of events not possible until very recently. Big History elucidates a timeline in rapid-fire succession, from the origin of the universe to the present day. This high-level, yet comprehensive view across disciplines allows learners to plug their individual specialization of study into the larger picture.

For the theme of energy, I chose to take an expansive definition in order to give students ample latitude to pursue their own particular research interests. For example, all of the mega-innovations over the course of human history involve releasing new flows of energy – including some that we don’t often stop to consider. With the Agrarian Revolution, which began around 10,000 years ago, humans systematically extracted the energy from photosynthesis – essentially captured sunlight. This caused a big change in lifestyles. Prior to that, human ancestry spent roughly two million years wandering the earth as hunter-gatherers – by far the dominant era of human history in terms of duration.

Another, more recent mega-innovation involved harnessing fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas, which constitute other forms of captured sunlight. The Industrial Revolution represents a recent and profound transformation of human civilization, activity and lifestyles – first with steam power, then later with more efficient internal combustion engines.

The ability to tap these new sources doubled human energy consumption during the nineteenth century. Then in the twentieth century, energy consumption rose by a factor of ten – much faster than the rate of increase in human populations.

Unleashing such enormous energy flows reverberates widely across regions and continents. According to Christian, diesel pumps remove freshwater from aquifers ten times faster than natural flows are able to replenish them. We produce minerals, rocks and other forms of matter that have never existed before, such as plastics, pure aluminum, stainless steel and massive amounts of concrete. Intelligent and practical public policy should inform our capacity to harness vast quantities of energy and their associated products.

According to Christian, most modern educational systems don’t spend much time working with students to look at the future in a systematic fashion. Big History presents an opportunity for undergraduates to see the long arc of how we arrived at this precise moment in time and – as future policymakers – to articulate thoughtful scenarios about the path forward.

Professor Wendy Petersen Boring at Willamette University sees her best weapon to combat climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental injustice as her students. Her approach is to teach courage, resilience, flexibility, creativity, and compassion.

Teaching to the Existential Experience of Climate Change

By Wendy Petersen Boring

My students are the source of my hope that we will emerge in the twenty-second century with a public life marked by greater equity and compassion and systems that protect the value of the natural world. Awake, resourceful, and resilient, they understand that we are facing an unprecedented crisis and they continue to work and create with integrity, intentionality, and courage.

When I first published a book on how the humanities and social sciences contribute to sustainability education in 2014, I focused on the ways in which teaching sustainability makes education better: project-based learning, community partnerships, and environmentally-focused syllabi develop an ethic of care for the natural world and optimize student skills in interdisciplinary problem-solving and systems thinking. This is important work. But it is not enough.

I believe we need to teach directly to students’ existential experience of climate change, species loss, and environmental injustice. For me, this means many things.

Each time I walk into a classroom, I assume that we are in this together. It’s not “their” problem; it is our collective work to do. I assume my students have strong emotional responses to climate instability and species loss that need to be acknowledged and that their grief and anxiety are in fact are powerful resources for their desire to create change. I assume that multiple and creative possibilities for transformation, mitigation, and adaptation still lie in front of us and that each student will find significant ways to contribute.

I teach with these assumptions not because I’m naively cheerful, but because I have made a conscious choice to do so. It seems the only ethical response to my student’s strength and their vulnerability. I also believe it is the only way the creative possibilities we need so desperately will emerge. I bring to the classroom my own strengths and vulnerabilities, and I try to bring some of my own experience of tapping into deeper sources of compassion, wisdom, and love.

Post-Trump, climate anxiety spills over into the center of the classroom and the fear, urgency, and sense of powerlessness is palpable. My students arrive in class with an instinctual sense of complete system breakdown. They are caught between paralysis in the face of seemingly intractable patterns of inequity, denialism, and limitless consumption, and the swirling possibilities arriving daily in their podcast feeds from movements inviting us to reimagine our future.

We need to develop inner resources that will endure through election, cultural, and species losses and that will empower and motivate us to respond creatively and act morally. A few years ago, I began creating new classes organized around cultivating the qualities it seems we will most need in the climate to come: courage, resilience, flexibility, creativity, and compassion. If grief, anger, and fear are the emotional side-effects of climate change, then classes like “The Inner Life of Activism” and “Creating Stories for Social Change” testify that mindfulness, compassion training, and catalytic storytelling provide the antidotes and material for the way forward.

At the same time, students need to feel a sense of agency. In “Western Civilization and Sustainability,” students trace the long arc of unsustainable history, but also follow the astonishing array of new stories, institutions, and technologies humans have created in response to massive upheavals. It becomes clear that we have reinvented “what it means to be human” many times over, and that they can participate in recreating what it means now. We ask the big questions, unanswerable from any single discipline or perspective. What is worth sustaining and why? How can we live morally on a planet that will undergo the multiple crises associated with climate destabilization? Asking wicked questions readies our minds and souls to tackle the wicked problems in the climate to come.

Perhaps most central to our existential moment is the need to nurture a sense of creative possibility. I believe new cultural forms are gathered instinctually, analytically, and unpredictably out of a creative re-combination of the old. As one of my students put it, it will take the “full canon” of human experience — the material, the intellectual, and the spiritual — to create a new story of who we are. Our classrooms should be the space for this creativity to be nurtured and thrive.

You can also read Wendy’s latest blog on the MAHB website.

Student Perspectives

Intellectual and personal development is a lifelong process. We find inspiration from these student’s reactions to the courses featured in this newsletter. Perhaps one of the single most important things we can do is to inspire and empower younger generations to be well equipped problem solvers.

Priscilla Trinh- University of Minnesota, Realty 101 with Professor Nate Hagens

“…. the Reality 101 mindset is basically esoteric and once filled with this knowledge, one is trapped in a vastly clearer but debatably smaller school of thought. Which is precisely why more classes like this should be taught.”

Ilan Palacios Avineri, Economics and History double major (‘19); incoming History PhD student at University Texas, Austin; interested in Religion, Ethics, and Politics in Cold War Central America

Ilan Palacios Avineri, Economics and History double major (‘19); incoming History PhD student at University Texas, Austin; interested in Religion, Ethics, and Politics in Cold War Central America

“Professor Petersen made clear that our 21st-century conundrum was not merely a question of public policy or even political will…Ultimately, (she) taught me that answering such a difficult question requires the full canon of human experience…”

Matt Tschirgi, History major (‘16); currently a sales and marketing professional working with organizations to improve sustainability in real estate in the San Francisco Bay Area, California.

”There are few people or classes who genuinely change the way you perceive the world in college…we can no longer solely think differently about the issues we face, we must in fact become different to face them.”

Montana Miller, History and Environmental Science double major (‘16); currently working as a social studies teacher and on a small, coastal farm and earning her Master’s in Teaching at University of San Francisco, California.

Montana Miller, History and Environmental Science double major (‘16); currently working as a social studies teacher and on a small, coastal farm and earning her Master’s in Teaching at University of San Francisco, California.

“My knowledge acquired… allows me to use teaching not only as a platform for presenting the unprecedented challenges we collectively face as a society with regards to the environment, but also as a way to engage students in the depth, complexity, and urgency that come with these problems.“

Donald Swen, recent graduate of a 3-2 dual degree program with a B.A. in Physics from Willamette University, a B.S. in Materials Science Engineering from Columbia University, a Physics major (‘18) from Willamette University and an Engineering degree, Columbia University (‘19). Currently working on implementing water systems in Ait Bayoud, Morocco.

“Professor Petersen’s class…turned my amorphous relationship with environmental sustainability to one of active passion. She equipped me with a historical understanding that let me see how values and lifestyles can adversely shape the political, economic, and social decisions we make…..[and] gave us space to reflect on what sustainability means to us and to imagine our earthly stewardship.”

Jake Kornack, Economics major, History minor (‘19); currently Interim Board President, Our Climate

Jake Kornack, Economics major, History minor (‘19); currently Interim Board President, Our Climate

“Professor Petersen teaches her students that history is the product of human decisions that were anything but predestined, and that we all can — and should — take part in the decisions driving human welfare today….[Learning about] the long view provided by history gave me a greater sense of what my role could be in the world.”

Margaret Woodcock, educator and high school librarian with a B.A in History and English.

“There is an imminent need for change, and Professor Petersen helped me see that the necessary cultural revolution is happening in moments of listening, humility, joy, and tenderness.”

Clara Sims, History and Religious Studies double major (‘19), currently working in sustainable living, bio-regional food systems and wilderness education in Taos, New Mexico.

“Professor Petersen’s classes have been immensely impactful in understanding sustainability and my own agency as a historical actor embedded within both human and ecological landscapes. This pedagogical strategy fostered my ability to understand and access an empowering narrative of my own agency…[and] has allowed me to both face and take action to mitigate the grim prospects of our collective ecological crisis with a hope that goes deeper than optimism and is rooted in a historical understanding of the evolving dynamics and immense resiliency of life, both human and more-than-human”

Arabella Wood (‘20), born and raised in San Francisco Bay Area, currently a senior at Willamette University studying Environmental Science and interested in pursuing climate and food justice.

“Professor Petersen’s classes have influenced me in not only my interests in paths post-graduation, but also in how I interact with the world…I learned about the overwhelming complexity of our food system and the injustices it perpetuates.”

My [Bill Davis] WMU undergraduate BFA students were assigned to photograph light pollution in their communities. Because there is a strong need for artists to consider their impact, students were asked to track, as much as possible, their environmental, social, and economic activity perceived as both positive and negative– as both artists and consumers. Light pollution was the subject matter but creative practice was the cornerstone. More in depth research can be found in the upcoming MAHB blog. Some summarized answers follow.

“I do feel that we need to have more conversations about light pollution so that we can develop more empathy…..I would say that my overall health increased during this project because I experienced more. Photographing light at night is a kind of meditative process.” – Ian Webb – WMU Frostic School of Art Photo and Intermedia Major (2017)

“I must partake in this consumerist culture to gain financial independence so that I can later support my own prosperity” -Photo and Intermedia and Intermedia Major

“Hypocrisy cannot be removed from everything. It isn’t right to do things then tell others not to do those same things just as it is right to do things then tell others to not do those things.” –Sculpture Major

“I would like to see photography become more sustainable in the artificial lighting department. It can be more energy efficient. If an alternative could be developed in the mining of minerals for consumer-level production, then that could be a giant boom– not only to environmental sustainability but to human rights conditions. -Sculpture Major

“I would like to see more efficient infrastructure developments, such as improve battery technology and less resource-intensive printing methods in terms of resin coated papers and optical brighteners that produce hazardous waste.” – Photo and Intermedia Major

Summary and outlook

The invention of the lightbulb started brightening up our world more than 150 years ago. It now affects life on Earth so dramatically that it turns night into day, changing the natural rhythm of light and darkness. Bill Davis’ beautiful yet haunting images of the illuminated night sky expose what the natural eye isn’t supposed to see – instilling a battle between beauty and the forbidden and forcing us to consider the price tag for what is destroyed by artificial light.

Thomas Tunstall links upcoming scholars from different disciplines with a high-level but comprehensive “Big History Framework”, systematically looking at the course of events from the origins of the universe to where we are today, and exploring how we got there. This enables students to put their individual specialization into the bigger picture, engage in public policy debate, and to articulate thoughtful scenarios for the future.

Wendy Petersen-Boring acknowledges her students’ strong emotional response to environmental destruction. Her aim is to foster resilience and to nurture a sense of ‘creative possibility’. By developing her students’ inner resources and cultivating the qualities most needed for tackling the challenges ahead, emotions like climate anxiety and grief can be transformed into powerful catalysts for change: we have the power to re-invent what it means to be human.

The success of these highly interdisciplinary approaches was echoed in the students’ voices. Despite coming from different scholarly disciplines, what they have in common is a better understanding of the world, a changed perception of it and their place within, and the knowledge that creating a better world is possible.

With life on Earth at a tipping point, getting us out of this disastrous malaise requires systems thinking, interdisciplinary approaches and a unified way forward. There are no excuses; every discipline will have to examine our existing social, economic and institutional systems, and to radically rethink the encrusted belief systems that have led us to where and who we are. Education, therefore, has a crucial role in equipping tomorrow’s leaders with the full armory of tools and coping strategies – ready for facing the challenges ahead and forging new paths.

We presented three different methodologies on ‘teaching sustainability’ but the underlying theme is also about lost places: the dark night sky, landscape, a sense of being and belonging, our home. Recovering these places is integral to our physical, mental, and spiritual existence. Looking towards Mont Blanc in 1854, the English painter and scholar John Ruskin wrote: “Every day here I seem to see farther into nature, and into myself — and into futurity”. Perhaps our species will have to lose many more places before realizing what is gone. Perhaps, to appreciate light, we have to experience darkness.

An incredible THANK YOU to MAHB volunteers Dr. Sibylle Frey, Oscar De Uriarte and Jonathan Staufer for their support in developing this MAHB Newsletter.

Thank you to William Davis, Thomas Tunstall, Wendy Peterson Boring, Priscilla Trinh, Ilan Palacios Avineri, Matt Tschirgi, Montana Miller, Donald Swen, Jake Kornack, Margaret Woodcock, Clara Sims, Arabella Wood, and students from Western Michigan University. The MAHB greatly appreciates your contributions to this newsletter and the inspiring work you’re doing.

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.