Art as Catalyst For Pollinator Conservation

Butterflies are some of the most resilient insects on our planet. Charles Darwin once wrote that “evolution is written on the wings of butterflies.” They appeared on our planet nearly 150 million years ago and have since remained relatively unchanged. They play important roles in the ecosystem of our planet and are considered indicator species that can help provide insight into the health and biodiversity of their environment. Yet, despite their longevity, many butterfly species throughout the world are under threat of extinction due to climate change, habitat loss, and misuse of chemical pesticides. In the US, many butterfly species are experiencing an alarming population decline. Take the Western Monarch, which once existed in the tens of millions, and has now dwindled to a mere 28,000. Without immediate intervention, its trajectory toward extinction is certain. Currently, there are approximately 96 known butterfly species across the globe that are experiencing similar phenomena. To understand the climate crisis and find solutions for a better future, awareness is our first step. I am an artist at the emergence of that fight.

My paintings are strongly influenced by nature. Much of my earlier work consists of visual commentaries on the fragility of our ecosystems, often through the juxtaposition of heavily researched subject matter—a fawn with patches of a spring meadow growing from its rump, or a fox being lifted by a flock of warblers—to name a few. Despite many of these paintings depicting surrealistic events, my artistic process involves copious amounts of research. Ensuring my work is accessible to both a scientifically minded audience as well as an expressive one, consumes my thinking. I desperately seek to discover the harmonious sweet spot between these two worlds.

My thirst to reach these very different audiences took a major turn in the summer of 2013 when I tagged along with a tour group to visit the research collections of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science – an assemblage of millions of zoological specimens, unintended for public display; carefully collected and preserved awaiting future scientific study. As an artist, this was the ultimate playground. The series of paintings inspired by this visit, titled Still Life, calls attention to specimens found within the research collections. The title is a play on words nodding to the notion that my subjects have a new life to breathe after death and to reference the historic practice of painting immobile objects from observation.

While Still Life highlights a range of ornithology specimens from collections in Denver and across the US, hummingbirds are a recurring subject matter of the series. I am enthralled by their diverse morphology—a byproduct of their lifestyle as pollinators. Take, for example, the Sword-Billed Hummingbird, one of the largest species, with a beak spanning nearly twice its body length. It has coevolved with the Passiflora mixta, a type of perennial vine native to South America which has an unusually long corolla hiding the plant’s anthers and stigmas. Thus, the Sword-Billed is the flowers’ exclusive pollinator.

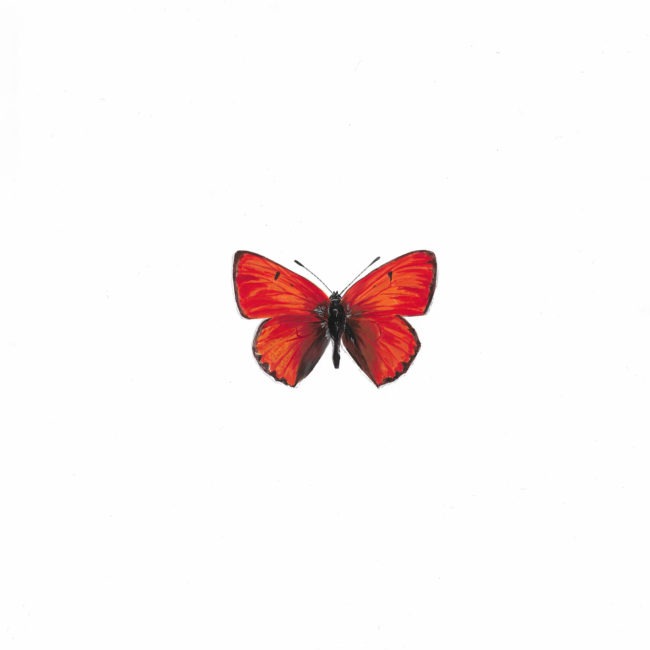

Although my first focus was on birds, my body of work has quickly expanded. Entomology collections with boundless assemblages of butterflies from around the world also intrigue me and research of my subject matter remains at the forefront of my artistic practice. I am captivated by their beauty, but also fascinated with their story. In 2020, my work experienced an emergence out of the realm of simple aesthetics and into environmental activism. In a joint exhibition titled At the Verge alongside Denver-based artist Faith Williams, we set out to tackle the crisis that pollinators across the world are facing due to climate change and other human-caused factors. The rise and fall of the Western Monarch is the ultimate tragedy, yet it is not the only species that faces extinction in the contemporary age. Sparking awareness with our audience has become a true priority.

Many of the resources that exist to document and detail species in peril fail to appeal to a wider crowd. A vast majority are conglomerations of academic terminology, often lacking the power of visuals. To the average individual, it is easy to pass over such important information, let alone connect with the scientific community on a common understanding. This presents a challenge – without a visual connection, conversations about climate change and its effect on our planet’s pollinators simply will not happen. My paintings aim to bridge that divide.

I paint butterflies swaying on either side of the brink toward collapse. Using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (ICUN) Red List of Threatened Species, I comb through an extensive list of individuals classified as either endangered or extinct. Once a selection is made, I scour museum databases for photographs of real specimens and paint each of them at life-scale on white-washed basswood panels. Some subjects, like the Western Monarch or the Florida Leafwing, are more familiar to a general audience, while others remain beacons of newfound curiosity. On the wall, I display these pieces in a grid-like fashion. Initially appealing to audience members through beauty and splendor, they soon become striking representatives of the realities of a human-caused environmental crisis.

I have also chosen to paint seven globally extinct butterfly species, each modeled after actual specimens found on the shelves of research institutions throughout the world. Only a handful of these rare insects have been preserved for study making them some of the only individuals of their kind in existence today. Introducing them into my painting practice has felt both like a privilege and a calling.

In addition, At the Verge has provided an opportunity to create real change. COVID-19 marks a time where many institutions are eager to digitally showcase artists and their work. I am the first non-South American artist to be featured by The Museum of the Institute of Agricultural Zoology (MIZA) in Venezuela. Through collaborations with organizations such as Creature Conserve, The Endangered Species Coalition, The Pollinator Project, The Chicago Field Museum, Moxie Writing Company, and many more, At the Verge has spread awareness of population fragility among pollinators and continues to provide a platform to fund conservation efforts around the world.

While pollinators face an uncertain future in the wake of climate change and human encroachment, there is still much we can do to combat it. Planting native flowers, reducing the use of chemical pesticides, and campaigning for better legislation to protect pollinators, like the Western Monarch, from further devastation are just a few of the ways how we can get involved. I hope to continue to bridge the gap between the worlds of biology and art. Most of all, I strive to invoke conversations about climate change and advocate for pollinators around the world within my work. We cannot protect what we cannot see.

Brandon Finamore was born and raised in Lakewood, Colorado, and currently resides in Broomfield with his wife, Hadia, and their dog, Bentley. In addition to his role as artist and conservation advocate, Finamore is also the visual arts teacher at Kearney Middle School in Commerce City, Colorado. His work can be found in collections throughout the United States and Australia. His work from At the Verge has raised hundreds of dollars for pollinator conservation and research.

ANIMAL GROUPS, An Exhibition Produced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C.

Pollinator paintings by Brandon Finamore are featured in ANIMAL GROUPS, a museum exhibition produced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C. The exhibition premiered over the July 4th weekend at The Dane G. Hansen Memorial Museum in Kansas to celebrate the opening of its newly renovated building and will travel to The Sternberg Museum of Natural History at Fort Hays State University in Kansas for display during the Fall Semester of 2021. The exhibit will feature 9 groups by 9 artists, each represented by five thematically related works to allow visitors to experience the breadth and depth of each artist’s treatment and expression.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org