The Sierra Nevada runs 400 miles north-to-south and approximately 70 miles east-to-west, and contains three national parks, 20 wilderness areas, and two national monuments. While the Sierra is populated with hundreds of lakes, the largest alpine lake in North America and the jewel in its crown is Lake Tahoe.

The spectacularly scenic environment of the Tahoe Basin is bordered on one side by the arid American Outback that is mostly Nevada and on the other by the Californian cornucopia measured by agriculture, industry, and technological innovation. Northern Nevada’s critical dependence on mountain reservoirs, the vast agricultural lands of California’s Central Valley, and the cultural mecca of the Bay area are inextricably woven within Lake Tahoe’s environmental history.

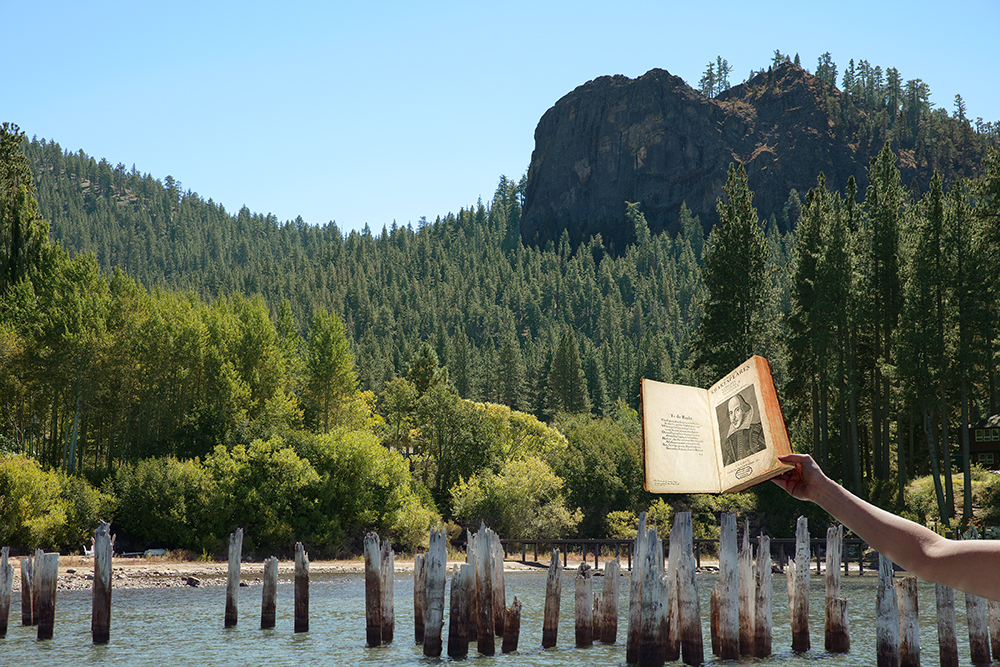

Shakespeare Rock, named in evidence of Euro-American colonialism, overlooking Glenbrook, Nevada. This is Glenbrook Bay, to the Washoe people, ʔát́abiʔ šámat, where the fish come from.

My introduction to Lake Tahoe was relatively late in the scheme of things; 1975, before I imagined living within the Lake’s lore. At that time, I was, as many before have done, passing through on my way to somewhere else. I was testing the climate of San Francisco, itself a beckoning mirage of tolerance, youthful thinking, energy, and flavorful living. Ultimately, I did move to the Bay a scant three years later. My personal tale was one of simple wanderlust; I had seen the limits of a regular, predictable life and wanted to pursue adventure and travel, first with a writer friend with whom I spent nearly eight months camping and gypsying throughout Central America. Such a trip would be nearly impossible today, folly at best and dangerously risky at worst. As Bob Dylan wrote in his first album of original compositions, The Times They Are-a-‘Changin’…the stark ballads captured the spirit of social upheaval that characterized the 1960s. The song’s title phrase is an anthem that reaches across the divide that separates us, whomever we have been or might be. The cultural landscapes of Mexico through Panama are forever changing, as am I, as are we all. These lands that Nevadans and Californians call home were once part of a larger Mesoamerican empire, although “empire” may imply a much more dramatic identity of infrastructure and control. The indigenous people, Sierra Miwok, Kawaiisu, Northern Paiute, Mono, and Washoe, were of the land, while others from regions far beyond the inland basin and range country, roamed and settled with various states of permanence. Immigrants arrived from the collective combine of the Columbian Exchange, which is a diffusion of Old and New Worlds, including but not limited to plants, animals, and bacteria. Change is not the exception, but the rule. The times may be changing, but they always have been, and yet the landscape is altered now more than ever.

Low water reveals the remnant of a boat’s hull near Emerald Bay Boat-In Campground.

The fabric of the history of Lake Tahoe is a complex weft and warp; pre-history merges ancestral Washoe identity with an ever-expanding narrative of conquest and settlement, extractive industry, exploitation, heroic adventures, mythic wilderness tales, frozen memories, iconic legacies, and grand vistas ready for consumption by a willing and eager public. On one level, Lake Tahoe provides a welcome respite from the rigors of industry, high-speed highways, sprawling suburbias, and a lifestyle that is defined by ever faster everything. But like the magical Land of Oz, living in the Lake Tahoe region, which includes Northern Nevada, is an experience in a kaleidoscopic kingdom of the Anthropocene. Nevada, Spanish for snow covered, has been a libertarian oasis for escapees from the progressive ideologies of inclusiveness and innovation, experimentation and tolerance. Protected landscape zones abound within the Sierra; not the kind with enclosed animals imprisoned within chain-link compounds, but the kind of landscape preserved for future generations to enjoy as a physical reminder when a more idealized geography was imagined to exist. The word imagined is critical herein because so much of the Tahoe Basin is subject to misunderstandings, exaggerated claims, reductive analysis, and presumptive ownership. Lake Tahoe’s legacy is on another level a private playground for the ultra-wealthy, from George Whittell, Jr.’s Thunderbird Lodge and his eleven miles of Nevada shoreline to the ‘Lucky’ Baldwin and the Pope Estates, to Lora Knight’s Vikingsholm, the Hellman-Ehrman Mansion, and today, to Larry Ellison’s multiple Tahoe properties that are evidence of Oracle’s success. In 2014, Ellison’s two and a half acre home along Snug Harbor Road sold for $20.35 million and in 2017, his Lawrence Investments acquired the Cal-Neva Resort and Casino, site of prohibition raids, tragic fires, numerous lawsuits, alleged fraud and deception, notorious mobsters, indeterminate Marilyn Monroe visits, secret tunnels, and glitz and glamour, promoted, of course, by Frank Sinatra’s tenure as majority owner.

Harold A. Parker’s postcard, The Lady of the Lake, Lake Tahoe, circa 1908, re-visited and rephotographed by the author’s team in 2016.

Lake Tahoe is the stage where Samuel Clemens, a la Mark Twain, inadvertently set fire to the shoreline forest and wrote about the beauty of flames reflected upon calm waters, where fanciful tales of perfectly preserved corpses float through eternity in watery depths, and where the Donner Party’s ghosts roam. Heralding Ski Lake Tahoe’s economic boom, John “Snowshoe” Thompson used rudimentary skis to carry the U.S. mail over a 90-mile trek from the Sierras down to the Carson Valley. Lake Tahoe is the theater for the saga and legacy of Duane L. Bliss, from lumber baron and progenitor of much of Glenbrook’s history, steamship Tahoe and the famed Tahoe Tavern, to the penultimate paternal figure memorialized in California’s D.L. Bliss State Park. The entire Bliss family, saluted by author Sessions S. Wheeler in his 1992 biography, Tahoe Heritage, has left their mark on Tahoe’s identity. A literal who’s who of the rich and famous, and well-known political figures from Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes, to John F. Kennedy graced Lake Tahoe’s shores, and that trend continues to this day. Lake Tahoe is also where Louisa Keyser, Dat-So-La-Lee, made baskets dance and John Steinbeck proclaimed after eight wintry months as a caretaker at Cascade Lake…that only lust and gluttony are worth a damn. Imagining his self-made fish-gut condoms suffices as proof of the seriousness of his proclamation. Lake Tahoe is the landscape that celebrated naturalist and environmental philosopher John Muir proposed as a National Park, a story encapsulated in the book’s chapter, To Be or Not to Be a National Park. Philosopher Bertrand Russell, in a retreat from his own complex struggles, and settling into a rustic Fallen Leaf Lake cabin, wrote while nude the classic Inquiry into Meaning and Truth. And lest Russell’s accomplishments reside only on the margins of Tahoe history, George Sessions, coauthor of the seminal 1985 Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered manifesto, credits Russell as an important inspiration. Summertide, the Crystal Bay estate, was once owned by aviator, business magnate, producer and eccentric Howard Hughes. Lake Tahoe is also where a landscape contractor from Fresno, California extorted Harvey’s Resort Hotel and Casino for three million dollars, resulting in a thousand pounds of dynamite exploding in a devastating mix of shattered glass, twisted steel, and pulverized concrete. These and numerous other interminable stories have become Lake Tahoe’s ethos; compelling, magical, illusive, unique, and paradoxical.

When all is said and done, from understanding the web that is the economic engine of the Tahoe Basin to the simple pleasure of viewing the Lake’s deep, crystal-clear waters, Lake Tahoe is the canary of the Sierra, a barometer of environmental health, of our national salvation, a limnological symbol whereby water is clearly the essential core of life, itself.

~~~

“The Nature of Lake Tahoe: A Photographic History, 1860-1960″, published in 2021, is available for purchase on the University of Mexico Press website.

Floating Earth Ball, encountered on a calm day on Lake Tahoe.

Peter Goin ~ A Visual Story Teller

First off the presses was Stopping Time: A Rephotographic Survey of Lake Tahoe and then Lake Tahoe and South Lake Tahoe Then & Now and then Lake Tahoe A Maritime History followed by Emerald Bay and Desolation Wilderness.

Peter Goin is not just a visual story-teller, but a writer, researcher, scholar, and photographer who spends extended time along the byways of Lake Tahoe’s flue trails, peaks, beaches, paths, Desolation lakes, and mostly now, on the water, from where the history of the Lake began. Embracing a lyrical and poetic vision of both place and books, Peter is an artist who bears witness to the evolving landscapes of the Sierra, Great Basin ranges, and beyond.

Peter is the author of books exploring paradigms of place, including but not limited to Tracing the Line: A Photographic Survey of the Mexican-American Border, Nuclear Landscapes, Nevada Rock Art, and Humanature and many coauthored books, from Black Rock to Time and Time Again: History, Rephotography, and Preservation in the Chaco World, and Dooby Lane and Colors of California Agriculture.

Peter’s photographs have been exhibited in more than fifty museums nationally and internationally, and he is the recipient of multiple awards from the National Endowment for the Arts to Nevada Governor’s Millennium Award for Excellence in the Arts.

Peter lives in Reno, Nevada.

Peter’s website: www.petergoin.com

This article is part of the MAHB Arts Community‘s “More About the Arts and the Anthropocene”. If you are an artist interested in sharing your thoughts and artwork, as it relates to the topic, please send a message to Michele Guieu, Eco-Artist and MAHB Arts Community coordinator: michele@mahbonline.org. Thank you. ~