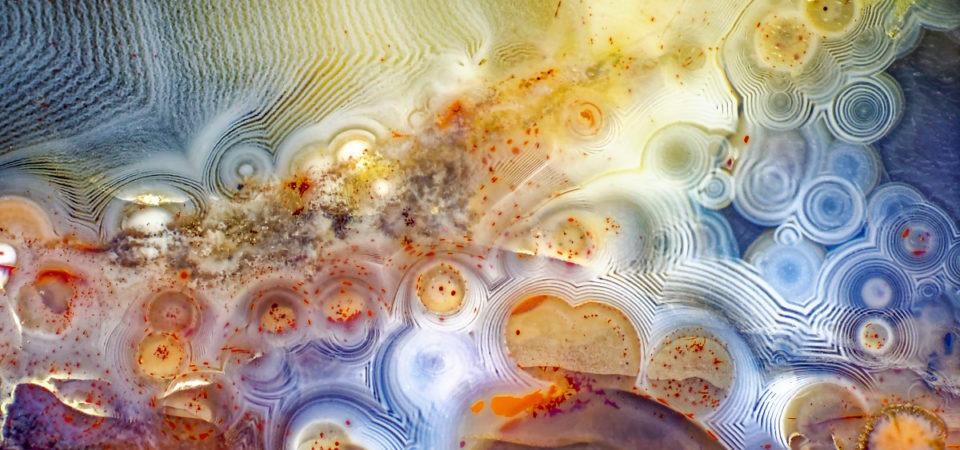

Joe Cantrell – Berber agate (detail) – Joe Cantrell © 2021

This is the third piece of four interviews in the series

Disclaimer: I do not support the tokenization and extraction of Indigenous knowledges and people. Upholding ways that respect and honor Indigenous knowledges and people is of the utmost importance. Every Indigenous interviewee and artist has given me their consent to share their words for this piece.

Cameran Bahlsen

Spoken Interview with Sweeney (Hawk) Windchief

Cameran Bahnsen: What are the defining aspects of how Indigenous people view the Earth?

Sweeney (Hawk) Windchief: I would say the defining aspects are to not see the Earth as a resource, but from multiple indigenous perspectives, to see the Earth as a relative, and I think it’s couched in language. To the best of my knowledge, the Quechua language in Guatemala and in South America, as well as the Aymara language in Bolivia, both refer to the Earth as “Pachamama” which means “Earth Mother”. The same is true for Indigenous peoples in North America, it’s often referred to as “Mother Earth”.

CB: What traditions or stories have shaped how you view and treat the Earth?

SW: I think ceremonial traditions shape how I view and treat the Earth. Everything is directional, so again, it’s cosmological. When we think about the Earth, we see ourselves and the Earth as a part of something much larger, as opposed to the Earth being the center. We are a part of something bigger. I think that it comes in terms of the directions, and the entities that sit within those different directions. We certainly have beings that represent the Earth, the sun, the moon, the different directions. They’re not all human, some are human and some are represented by different animals and different beings. For us, the word “deity” or “god” doesn’t really explain it very well, that’s a western framework.

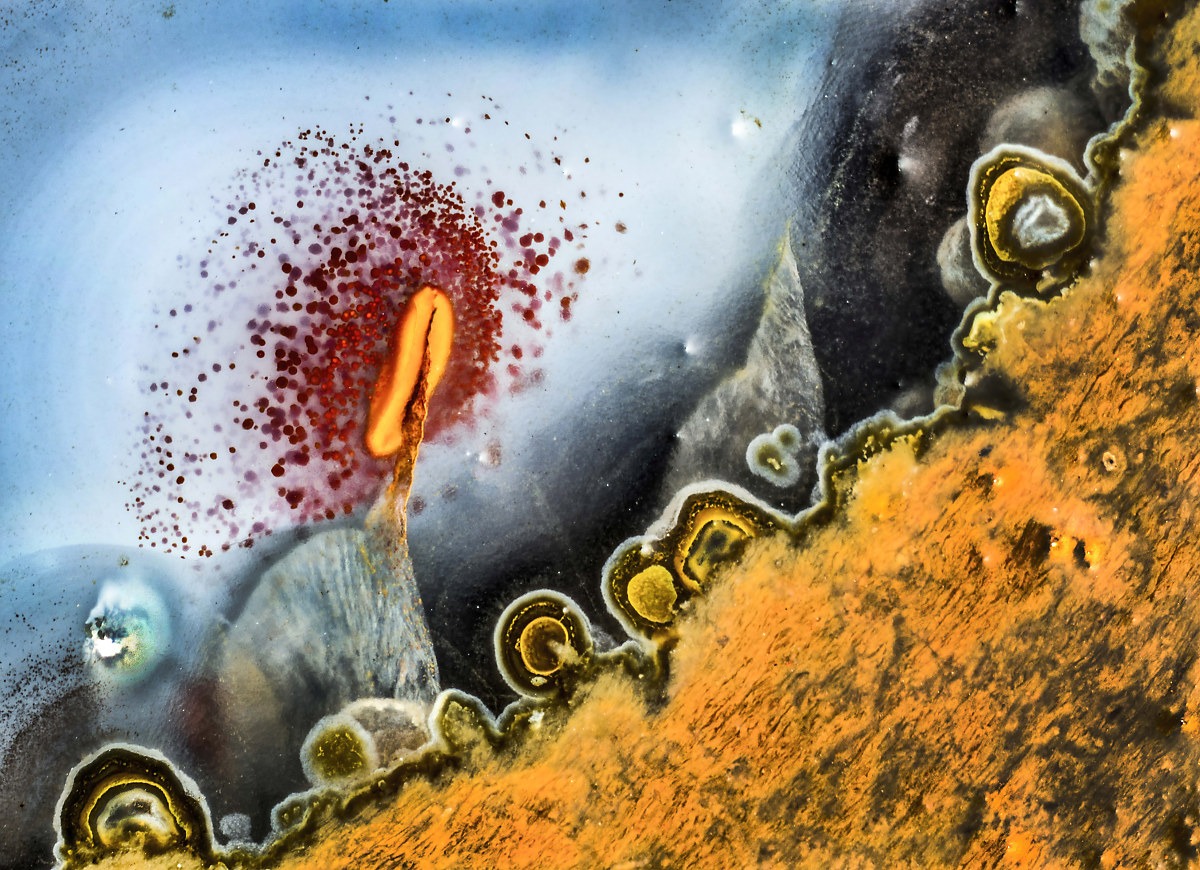

Joe Cantrell

This image appeared to me as a reddish-looking smudge in a sliced thunderegg I found in a flea market. It did NOT look in any way spectacular but the stone was cheap, I bought it, put it under my lens and found this. I regard it as the rock showing us a pictograph of ourselves. Nature joking back is part of the stereotype smashing.

CB: What do you think Western cultures can learn from Indigenous people when considering global environmentalism?

SW: I think it goes back to question one. Western cultures can learn from Indigenous people to treat the Earth as a relative, as opposed to something that can be resourced.

CB: What does the current climate crisis, often understood to include ecosystem/habitat loss, depleting natural resources, loss of biodiversity, and changing climates, mean to you?

SW: I think it shows that we’re dependent on the Earth Mother- she is not dependent on us. We need to understand that there has to be some sort of balance in this whole thing. Science will show, and has shown, that the climate crisis is a human phenomenon. In the big picture, she’ll (Mother Earth) recover, but we might not. Years from now, when we’re all gone, all those highways, interstates, pipelines, dams, all of those things, are going to go, they’re going to fade. Those are all human constructions that will not recover. But grass will recover through concrete. In the big picture, it reflects how we’re dependent on the Earth, not the other way around.

CB: How can Indigenous ways of understanding the environment allow us (humans) to change our relationship with the Earth?

SW: As Indigenous peoples move forward in this 21st century context, it’s important for all of us to understand that place-based knowledge is important. Indigenous peoples have a millennia of relationships with the Earth, and those relationships construct the way of life for those communities. To learn about environmentalism, from multiple Indigenous perspectives, we can’t practice those same things and be good inhabitants of the Earth. If we’re in the Pacific Northwest or American Southwest, where the landscape is different, the knowledge is different. So there is place-based knowledge that needs to be considered if we’re actually going to do a good job of taking care of Earth Mother.

Joe Cantrell

This image is Turkish agate, again, illustration of the joke of Persey Byshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias, King of kings, look on my works ye mighty and despair.” Dude, look what chemistry did without your messing it up!

CB: Is it important that the global citizenry activate Indigenous ways of knowing?

SW: If we want to live, yes. If we don’t want to cease to exist as people, the global citizenry has to pick up on place-based knowledge.

CB: Is it possible/appropriate to bridge the gap between traditional Indigenous environmental approaches and scientific knowledge to contribute to a more sustainable future?

SW: I think it is possible, but I think the hard part of it is an internal shift on behalf of people. I think that in order to bridge that gap, people, particularly those in places of influence, have to hurt first. I think people are incentivized by being able to live this high-quality lifestyle with as little sacrifice or work as possible. Say, for instance, we have to start paying huge amounts of money for water, then all of a sudden people are going to say “I remember when we could just turn on the tap”. I do think that can be avoided. Until that happens, I think we are going to have to hurt a little bit before we can make that shift.

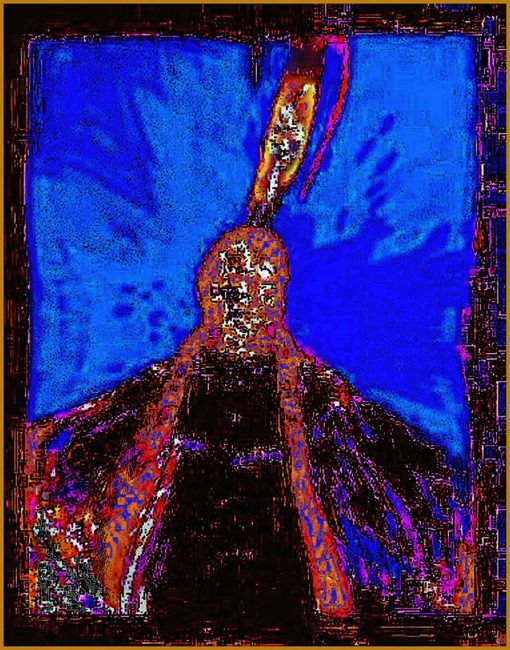

Joe Cantrell

This image is from the mid ’90s, my interpretation of many people’s concept of Indians. 1) Primitives on screens wearing feathers 2) John Wayne can mow them down for any reason he likes, from a running horse with pistols at 200 yards and he needs to because they are savages 3) The “pixelization” (it’s not) is from projecting a tiny reproduction of a painting of Red Cloud on a 1995 computer monitor. I photographed that tiny image with a medium format film camera, blew it up, played with the colors as I made a photographic darkroom print of it, and there you see it.

CB: What are some community approaches to addressing the fact that Indigenous communities are often disproportionately affected by climate change?

SW: I think it’s research of Indigenous knowledge within those communities, that would be one approach. To live as a community in a way that people understand we are part of the Earth. But at the same time, we are competing with the twenty-first century media and what we are being taught about that, so people are probably feeling conflicted about it. Another community approach is activism, such as #NoDAPL water protectors- this concept of blocking people’s extraction of the Earth’s resources in some way.

Joe Cantrell

This image is Comet Neowise, summer 2020, North Plains, Oregon, the Big Dipper on top and an aircraft’s lights in the landing pattern for Hillsboro, Oregon’s airport. At the bottom in the fir trees, The Rice Museum of Rocks and Minerals. Because pictographs happen in the sky too.

CB: What do you see as the largest barriers to enacting the change we need to see in order to live more sustainable lives and protect the Earth’s resources?

SW: I think the largest barriers are that we’ve been conditioned to live in a way that’s not in alignment with Earth’s traditional laws or ways. I’ve heard stories about particular ways to treat the Earth in an old-school context, and because we live the quality of life we do and have become used to it, we just expect that the water, and the infrastructure that supports water, is going to be there. When the light goes out and the tap runs dry, who knows what is going to happen. I mean, it’s hard to think about it. It’s also a little bit hypocritical of us to say that, when I drove my truck to work, or we’ll all go to this global environmentalist conference, and how many pounds of jet fuel did we all burn to get there? The economy has a huge part in this. I can go to the grocery store and get avocados in Montana. I like avocados and dig guacamole, and I don’t even have to think about it, I just go to the store and buy some. I do think that those barriers are the lifestyle we’ve learned to live thus far. If all of a sudden, we have to have regional diets based on a more sustainable way of food production, that would be something where everyone would need to make a lifestyle change that was in accordance with that. And I don’t think we’re ready to do that, because I like guacamole and live far away from my job. There are also the little things we take for granted.

CB: What support do you and/or your community need to better address some of the challenges and problems we’ve discussed today?

SW: I think the best example that I can give, as far as support, is the success that we’ve had at Fort Peck in reestablishing bison. I say that because a man named Jason, who lives in Wyoming and was a student at Montana State, runs the buffalo program down in Wyoming. I went to his Master’s thesis presentation on how bison affect the flora of the areas they live in. They are finding that where they reestablished these traditional bison herds, there are plants, traditional Indigenous flora, that are growing back. There are medicines that are dependent on bison being there. They have been dormant for years, but now because of the reestablishment of these herds, the biodiversity is coming back to where those buffalo live. Those animals have an innate sense on how to operate within nature’s laws. Two years ago, we were on a buffalo hunt, and I was talking to a person who was managing them [the buffalo herd], and he said it was kind of strange because there was all this grass, and feed that the bison can eat, but for whatever reason they (the bison) are not going there. People don’t know why the buffalo won’t go to certain places where the food is plentiful. But they also resist overgrazing. I think that if there is support that communities need to better address these challenges, I think it’s about reestablishing traditional food systems and water systems, and to develop a connection, and not take for granted the things we have. There are all sorts of good examples. There is salmon in the Pacific Northwest, problems that hydroelectric dams created there, there’s examples in American Southwest of uranium mining that’s a really big problem for the Navajo and Hopi there, there’s examples of it in any Indigenous community. A really good example of how global climate change affects Indigenous peoples was told to me by a lady from North Alaska, and she said there was no traditional word for ”dragonfly”, which is kind of crazy, that animal is moving so far North to a place where it didn’t used to live, to me is a signal of global climate change. It’s kind of a candy-coated version, she also told me that the polar bears there are starting to cannibalize each other. So not only does it affect humans, it affects all living things on Earth. Like bees for instance, and their connection to food production, genetic modification and putting patents on nature’s products is super problematic. There is this really cool story that talks about corn and traditional farmers of corn. Corn needs people, and people, in order to live, need corn. I remember hearing somebody reframe it and said maybe we’re not the ones who are changing corn, maybe corn is changing us…so it can live.

Joe Cantrell

Berber agate showing almost miraculous-looking organization, such perfection, pictograph of our own Universe and our place in it, on the dumber end of the scale.

Afterthought: I want to thank both Hawk and Joe for selflessly and humbly sharing their knowledges and time with me and the MAHB community. Hawk is my super rad uncle, and I look up to him and all he is doing for our people and the Earth. He has always kept his humor and relaxed manner throughout his work, which helps remind me that I can do the same while also enjoying life for what it is. I met Joe through Crow’s Shadow, and his kind spirit made me feel very welcomed. I admire his courage, commitment to Indigenous peoples, and his perseverance through everything life has thrown his way. I hope I can be just as selfless and helpful to the next generation as Hawk and Joe were to me.

Cameran Bahnsen

Disclaimer: The words and art of the featured interviewee and artist are independent of each other and only reflect their own viewpoints and opinions. They are not reflected through each other in any way.

Sweeney Windchief

Sweeney Windchief

Sweeney (Hawk) Windchief is a member of the Fort Peck Assiniboine Tribe in northeastern Montana and serves as an Associate professor at Montana State University. He earned his Doctorate of Education in Ed. Leadership and Policy at the University of Utah in 2011. His research interests fall under the umbrella of indigenous intellectualism to include indigenous methodologies in research, tribal college leadership, and indigenous student persistence in higher education. His teaching privileges include critical race theory, Indigenous methodologies in research, law and policy in higher education as well as other courses in the Adult & Higher Education program. He and his wife Sara have two sons who help keep things in perspective.

MSU photo by Kelly Gorham

Cameran Bahnsen

Cameran Bahnsen

Cameran Bahnsen was raised in Ventura County, located in Southern CA. She is part Assiniboine (Fort Peck Reservation, Montana) and currently attends the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is pursuing a B.S in Environmental Studies with a minor in American Indian and Indigenous Studies. At a young age, she grew up beach camping with her family, which inspired an early love for the outdoors. Her love of nature, coupled with her cultural connection, continue to drive her aspirations of working within resource management, environmental education, interpretation, tribal relations, and conservation. She enjoys hiking, camping, backpacking, cooking, listening to music, and spending time with friends and family.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

This article is also part of the MAHB Arts Community‘s “More About the Arts and the Anthropocene”. The MAHB recognizes the value and importance of learning and listening from Indigenous people. In an effort to honor Indigenous voices, if you are an artist that identifies as Indigenous and you are interested in sharing your thoughts and artwork, as it relates to the disrupted but defining period of time we live in, please contact michele@mahbonline.com