Biocapacity and the Built Environment in the Kenyan Landscape.

Photographer: Cecilia Wandiga, Executive Director, Centre for Science and Technology Innovations.

Images Clockwise: 1. Landscape view along Narok Road near Mount Suswa Conservancy. 2. University of Nairobi Buildings and City view. 3. Giraffes at Haller Park, Mombasa. 4. Emerging young scientist holding a microchemistry kit. 5. Clay architecture concept structure at University of Nairobi School of Architecture. 6. Base Titanium Kwale IUCN Red List tree nursery. 6. White sands and clear evening skies at Diani Beach.

WEBINAR Wednesday, July 21st, 8:00 am Pacific time

SEE ANNOUNCEMENT HERE

REGISTER HERE

The American astronaut Neil Armstrong’s space photograph of July 20th,1969, presented the first complete picture of the planet Earth which left everyone in awe. From then on, the planet became, ‘our’ planet. In the subsequent years, we began to witness an unprecedented metabolism outpacing the planet earth’s regenerative capacity in which the fast-growth countries were recording an increasing trend in their individual wealth accumulation. This trend birthed many of the global challenges we have today, like human inequality, climate crisis, and /or waste problem among others.

Numerous experts believe we are living through or on the cusp of, a mass species extinction event, the sixth in the history of the planet and the first to be caused by a single organism – us. This event serves as a red warning light for our societies and the planet.

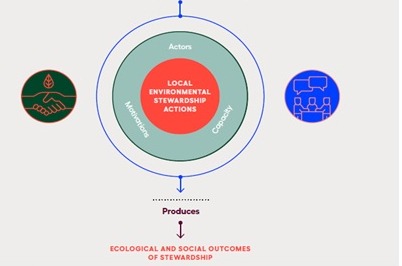

To solve these problems, efforts aimed at establishing sustainable practices that target to restore ecosystems for people, nature, and climate are underway. These efforts have, for example, seen a steady decline in extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is however not feasible to continue using the West’s growth yardstick because of the inherent dissonance between the expected ideals and actuality. This provides the central theme of this article aiming to tap from African environmental ethics. Many will agree that a new normal is coming. Covid-19 is the tip of the spear. Africa can adopt Bennett and others 2018’s conceptual framework for local environmental stewardship to establish her biocapacity measurement method in which social accounting is embedded into the ecological footprint metrics (see Figure 1).

In the broadest sense, social accounting is the requirement for those who produce goods from natural resources to explain and take responsibility for their choices and actions. At the core of it, every activity will aim for local environmental stewardship where people and nature become partners.

Knowledge of the ecological footprint measurement is familiar to everyone. The Global Footprint Network releases National Footprint Accounts (NFA) annually as an open-source database, including for African countries. Integrating the idea of a socially embedded eco-industry is novel thinking but relies on indigenous knowledge about the connection with the environment and the building of local resilience. The big question then becomes, how can production systems adopt a circular bio-economy? As an illustration, there are ways a society can adapt to new norms. In 2006, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) discussed the Mapping of climate vulnerability and poverty in Africa.

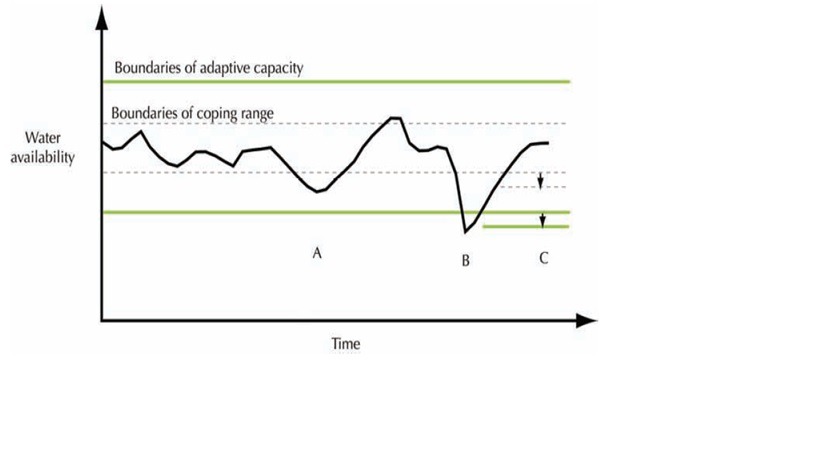

In Figure 2 they explain the representation of vulnerability, coping range, and adaptive capacity of a society. The figure shows the variation in water availability for a region with a limited coping range. At point A, the coping range is exceeded, but water availability is still within the adaptive capacity, and impact can be avoided provided that anticipatory and reactive adaptation mechanisms operate. At point B, the adaptive capacity is exceeded. Ideally, following hazard exposure, the region will learn and be able to expand its adaptive capacity for future situations (at point C). If the long-term ability of the region to expand its adaptive capacity is exceeded, then impacts cannot be avoided.

Africans are historically linked to their environment to which they attach great value. This then means that embedding a social accounting system in the local production framework will require the use of local assets like the Kiswahili language to pass on information. The same knowledge is transferred intergenerationally.

In addition, the innovation agenda should mostly be inspired by nature. For example, the UNESCO-associated Centre for Science and Technology Innovation, CSTI, the consortium anchor for Climate Change & Sustainability Basics CC&SB, is currently promoting a sustainable cities approach through Earth-Architecture in Kenya’s nascent bio-blue circular economy. This can bring great results especially if the social thinking in green production is embedded in the legal framework of all African nations, as Kenya has done it.

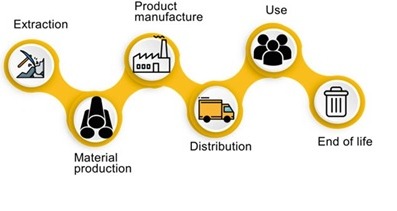

In 1947, C. S. Lewis wrote, “Everything connects with everything else, but not all things are connected by the short and straight roads we expected”. In other words, if we hope to meet the challenges of providing sufficient freshwater, food, energy, housing, health, and education to the world’s 9 billion people while maintaining ecosystems and biodiversity for future generations, we must all act together. This requires that we abandon the linear system of production shown in Figure 3 as is being promoted by the Ellen Macarthur Foundation.

In the search for alternative solutions to bring about more sustainable economies, the circular economy (CE) concept has become a popular model in many parts of the world. The CE model strives not only for rational usage of resources but also to minimize their need. By reusing those resources they promote wealth creation. Within this framework, this replaces the linear economic end-of-life concept with new circular flows through re-utilization, restoration, and renovation in integrated and systemic processes. In advocating the decoupling of economic growth from increasing resource consumption (a relationship otherwise perceived as inexorable), a CE redefines the functional flows of production chains and calls into question the hegemonic model characterized by wastage and disposal. This comes at a time when the industrial symbiosis system of Kalundborg in Denmark – a model of an eco-industrial park – received only low adoption.

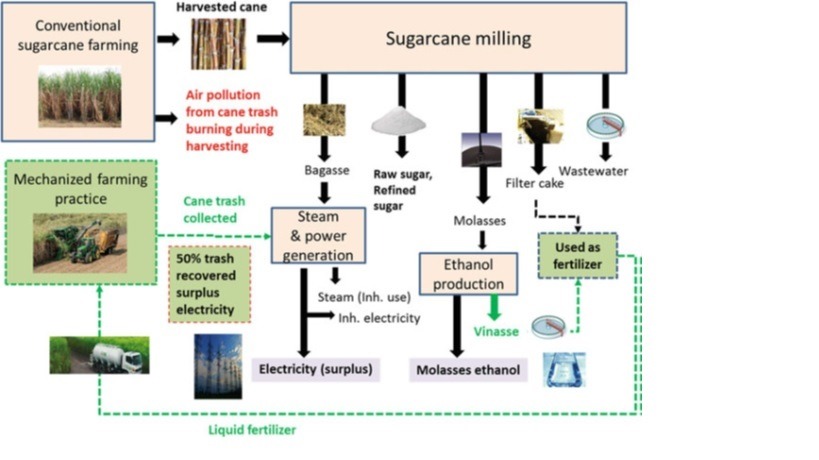

A life cycle analysis (LCA) of a circular economic model can measure biocapacity in an integrated manner including both ecological and social impacts. For example, an LCA for a sugarcane biorefinery system (Figure 4) showed that by changing production processes, impacts on climate change, acidification, photo-oxidant formation, particulate matter formation, and fossil depletion can be significantly reduced, including the trade-offs from increased energy and material use for mechanized farming, transport, and fertilizer production.

Africa, it is said, is in a rising mode. Her growth journey must be within her ecosystem’s biocapacity which is also in tune with the targeted social outcome. This can be possible if Africa adopts a bio-circular economic model powered by an African-Centered Ecophilosophy and Political Ecology. In this manner, biocapacity measurement for Africa will result in sustainable growth and hopefully, Africa may socially inspire other regions of the world to follow her path to return our planet’s ecological health.

Dr. Eng. Elisha Akech Ochungo has over two decades of practical experience in the transportation engineering sector. He has been extensively involved in highways and traffic studies. Now focused more broadly on the emerging circular bio-economy, Dr. Ochungo is the founder and principal of Climate Change & Sustainability Basics, a biocapacity measuring outfit in Kenya.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org