You walk in and find your friend already seated at a bar table near the back of the room. As you approach you note that they have gone ahead and ordered some glasses of wine and beautiful shrimp cocktails. You pull up a stool and prepare to dig in, but notice something unexpected –a large installation on the wall is playing a video. As you watch, you realize the video is showing the process of shrimp trawling in the Gulf of California. The process behind the shrimp so elegantly displayed before you. A process so rarely considered, shared, or depicted –something it has in common with many of our food systems.

The bar table described above is actually a piece of a larger exhibit showcasing the transdisciplinary work of Eric Magrane and Maria Johnson. Their work illuminating the shrimp trawling fishery of the Gulf of California is part of the 6&6 Collaboration. Forged by the Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers network (N-Gen, www.nextgensd.com), 6&6 is a collaboration between artists and scientists to explore the patterns and processes of the Sonoran Desert and Gulf of California. Through this collaboration Johnson and Magrane chose to use the case of shrimp trawling as an example of the disconnect between ourselves and the systems and practices that supply use with food. Through this work they pose challenging questions about extractive practices and the value we place on non-human life. They have found collaborating between the arts and sciences enables them to dig into these questions that often reside on the peripheries of a given field of study.

In addition to collaboration with each other, both Magrane and Johnson represent art and science working in synergy at the individual level. Magrane has a background as a poet and creative writer, but also as a geographer. On paper, Johnson is labeled as the scientist in the collaboration, with extensive experience researching the marine ecology of shrimp trawling bycatch in the Gulf of California. Johnson is also an illustrator. Magrane has found their ability to play multiple roles in the project very rewarding and feels that it has helped them in the collaborative process, “because neither of us firmly fits into those ‘artist’ and ‘scientist’ categories and neither of us is defending our discipline or way of seeing things.”

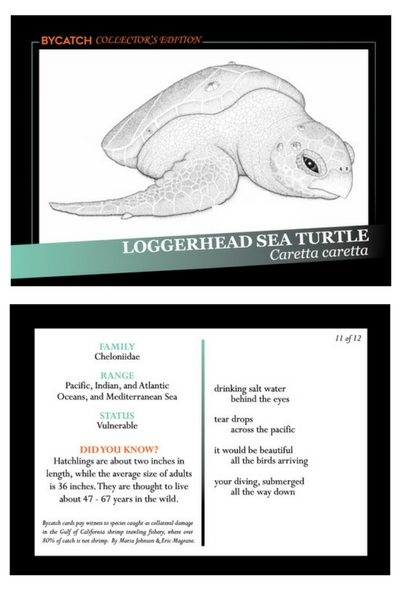

They have successfully tapped into their wide range of interests and abilities to create an array of creative outputs. Magrane describes the early stages of the project, “We started writing, doing poems and illustrations addressed to specific individuals and species that are caught as bycatch, which is 85-90% of what’s caught in the Gulf…” Magrane recognizes that writing poems to fish might seem absurd, but they have found it is a good way to prod people to reflect on “what respect we give that non-human other, and what does it imply regarding how we use the project to model empathy in the world for other species and each other.” Johnson and Magrane carry the question of how we value non-humans forward through a set of trading cards featuring species that often make up trawling bycatch. Johnson explains, “Each pack has 13 cards and on one side there’s an illustration of the species and on the other a poem excerpt and information about the species.” Magrane adds, “They’re like baseball cards or trading cards that give value in a certain way to these species that don’t have value as bycatch.”

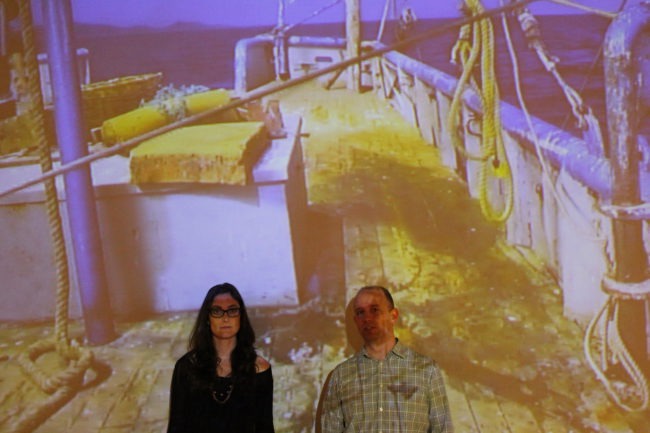

From February through April of this year, Johnson and Magrane shared their initial work at the University Of Arizona Museum Of Art through the exhibit Bycatch. They brought the illustrations, poetry, and cards together with video footage from their trips aboard shrimp trawlers along with a fully-set bar table. “There’s a nice bar table with finely folded, cloth, shrimp-colored napkins, wine glasses and fake, but very realistic, shrimp cocktails.” And then “There’s this big video installation of what’s actually happening behind catching the shrimp to get it there.” Magrane describes the video, “[The nets] get dropped on the deck of the boat and there’s this writhing mass of sea life. Some of it is alive, some of it is already dying…You look at this pile of fish and you don’t really see shrimp. They’re just maybe 10% of the catch there,” which he explains raises the question, “How did we get to the point in our current economic and food systems that this is the way that this happens?”

For people viewing the exhibit, Johnson explains, the video is “something that catches their eye and gives them a little background on how the people are interacting with the species and what the pile of bycatch looks like. It allows them to have context for the words and the poems and the species on the walls.” Johnson sees the video as the piece that “provides structure for everything else –the poems and illustrations and cards and table– to interact with.”

It is a combination Johnson admits she would never have anticipated: “You picture something in your mind before having a conversation about it but then it grows and changes and shifts and it becomes something else. The cards, table, video I never pictured that as part of an exhibit so I felt a slight hesitation because it was unfamiliar territory to me.” However, as they worked to share the complexities and juxtapositions of the trawling fishery they found that multiple media were needed. Magrane describes the moment where people walk into the exhibit, “they don’t know what they’re getting into and they see this real-looking shrimp cocktail and then see this video of this traumatic pile of fish on the boat and making that juxtaposition is part of the critique that the art is doing. The way that the exhibit works is through the conversations between the different forms and materials of the exhibit.”

Guiding these conversations is critical. Johnson explains:

“Something I feel challenged by is trying to communicate the topic of shrimp trawling in a way that highlights all the pieces of it, especially in thinking about our show at the museum. People walk in and stay for 10 to 15 minutes and they walk away with an idea of what that industry looks like. I think it’s really important that they walk away with a holistic understanding of what happens in the industry and why. Everyone has a different interpretation of what it means to them and what they do with that information. It’s such a complex issue and I feel it’s important to consider how to effectively talk about it or depict it in a way that people get the full picture.”

Magrane expands on this to clarify:

“We didn’t want anyone leaving our exhibit thinking we were simply saying that Mexican shrimp trawlers are bad. We were quite explicit in terms of critiquing that, but also this extractive mindset that’s the same mindset that plays out in narratives of fear and control… We want to connect the Gulf of California trawlers to broader forces in the world… to prod people to think about food systems, systems of consumption, and human-environment relationships in a different way.”

They recognize that this goal might leave people visiting the exhibit, along with Johnson and Magrane themselves, with more questions than answers. Following a presentation they gave during the UAMA exhibit, Johnson and Magrane received “a number of questions about ‘What do we do?’ And that’s a really tricky question.” Johnson explains, “It’s such a challenge to really understand what’s happening in a fishery, there’s so much hidden from us. Even if you’re trying to educate yourself it’s so hard to know what’s actually happening below the surface. More and more we learn about the social justice side of the fishing industry and how a lot of fishers are spending their lives and what challenges they go through, in addition to the environmental impacts. We’re trying to illuminate the reality of this fishery the best we can and let people make decisions from there.”

Combining art and science allows Magrane and Johnson to share far more aspects of this reality and its complexities than would be possible through a single lens. It also allows them to connect people with that reality in an emotional and thought-provoking manner. Magrane concludes, “The exhibit really works by the spaces in between the different aspects of it. In the same way arts-science collaboration works –in those edges, the spaces in between, in the eco-tones between disciplines or between ways of thinking, between ways of trying to make sense of what is happening in the world and represent it or critique it in some way.”

This project is part of the 6&6 collaboration introduced at the end of April. You can find out more about 6&6 here. The MAHB will be featuring additional scientist-artist partnerships from the collaboration in the coming weeks.

The above post is through the MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems and contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the space.

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/creative-expressions/bycatch-complextities/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.