This article originally appeared in Patterns of Meaning, a blog that explores the patterns of meaning that shape our world.

There was a resounding tone of history being made in Paris. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon was close to tears as he declared: “We have entered a new era of global cooperation on one of the most complex issues ever to confront humanity.” President Françoise Holland told the representatives of 186 nations:

You’ve done it, reached an ambitious agreement, a binding agreement, a universal agreement… You can be proud to stand before your children and grandchildren.

And it wasn’t just our political leaders who declared victory. The Guardian boldly proclaimed “the end of the fossil fuel era.” Prominent environmental organizations such as Climate Reality Project joyously announced: “This is the turning point… We won!” Even progressive grassroots organizations are delighted. “Today is a historic day,” writes 350.org. “We did it!”cheers Avaaz, “A turning point in human history.” How justified is this sense of triumph?

Much of the jubilation stems from the contrast to the mess of the Copenhagen summit six years ago. At that time, all attempts at an agreement collapsed in disarray, leaving the environmental movement in a state of deep depression. Since then, much of the planning around COP21 has been to avoid a rerun of that fiasco. Instead of calling for commitments from countries, the UN merely asked for intentions. Instead of targeting a realistic trajectory to save our civilization, the parties merely noted that much more needs to be done. If you set the bar low enough, even the smallest step feels like success.

In fact, not everyone has joined the ovation. Prominent climate scientist James Hansen – the first to bring awareness of the climate crisis to Washington –called it “a fraud really, a fake.” Other groups, particularly those focused on the needs of the global south, agree with his take. In this alternative account of the Paris Agreement, 186 countries arrived at an emissions plan that puts the world on a trajectory for more than a 3° C rise in temperature by 2100. They’ve all agreed this plan is woefully inadequate, but decided to do nothing about it for another five years, when they will re-examine their targets. Their agreement made no mention that the vast majority of fossil fuels are unburnable if we are to prevent climate catastrophe, contained no discussion of the huge contribution to global warming made by industrial agriculture, and ignored crucial issues such as deforestation and indigenous rights. In spite of the consensus among prominent economists around the world on the need for a worldwide price on carbon, the deal avoided any mention of that idea.

There was no mention, either, of reducing the $5.3 trillion spent every year on worldwide subsidies to fossil fuels. Even though the wealthy nations have emitted 60% of the carbon in the atmosphere, they agreed only to “mobilize” $100 billion per year of the $1 trillion per year it will take to develop a fossil-free economy, mostly to be spent by developing nations – an amount they won’t review for another ten years. Meanwhile, the developing countries most vulnerable to climate disruption, desperate to get the wealthier nations to agree on a global temperature rise goal of less than 2°, were forced to give up their right to seek compensation for the present and future devastation caused by the developed countries’ pollution.

But, in spite of its gaping shortcomings, I do believe something important and historic emerged from COP21. It’s not so much the size of the step the world has taken, as the change in direction. Until now, the world has failed to agree even on the target we need to achieve. At Copenhagen, the parties merely noted the scientific consensus that a 2° C rise in global temperature above pre-industrial levels would likely lead to runaway feedback effects, and since then that number became the de facto objective. Yet, out of the blue, in the early days of COP21, a so-called High Ambition coalition of countries began talking about a 1.5° target, which, given that we’re already at 0.9° increase, is a truly aggressive goal. And although the 1.5° number didn’t quite make it to the final agreement, the countries did agree to aim for a temperature rise far below the 2° level, along with a goal of net zero carbon emissions by the second half of this century.

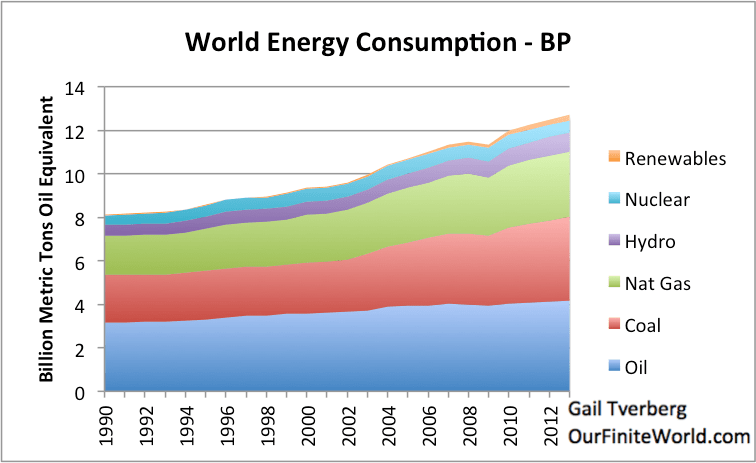

These new targets create a stark contrast between where the world agrees we need to go and where we’re currently headed. In fact, I would call it a chasm. Currently, fossil fuels account for 86% of the world’s energy, and that has barely changed over the last ten years. At the current rate of emissions, even according to Shell’s own climate advisor, we’ll be passing the threshold for a 1.5°C temperature rise by as early as 2028. Drastic changes will need to be made to every aspect of our economy – and fast – if we are to have any hope of reaching the Paris Agreement’s goal.

It is that very chasm, though, between target and current reality that gives cause for hope. As a result of it, we can expect far more talk about unburnable carbon. Divestment from fossil fuel corporations’ stock will become widespread as their market valuations are seen to be based on fantasy. The growing grassroots movement to “Leave It In The Ground” will become ever more unstoppable. A worldwide price on carbon, placed on it as it comes out of the ground, will soon become part of the public discourse. The renewable energy transformation, already under way, will burst into mainstream awareness.

The point is, as 350.org observes, that “Paris isn’t the end of the story, but a conclusion of a particular chapter.” It’s a chapter that has demonstrated clearly the power of the citizens’ movement. When Christiana Figueres, head of the climate talks, gave her closing speech to the summit, she emphasized the importance of the popular movement in forcing politicians to accept a new reality. “When in 2014,” she said, “hundreds of thousands of people marched in the streets of New York, it was then that we knew that we had the power of the people on our side.”

Citizen power was in evidence throughout COP21, in spite of the ban on public demonstrations. From the thousands of shoes placed in Place de la Republique before the conference began, to the golden sun painted ingeniously by Greenpeace around the Arc de Triomphe, the politicians in the Blue Zone knew their discussions were being closely watched by millions of citizens around the globe. Avaaz tells how, after the Indian Finance Minister came out against 100% clean energy, activists projected films of Chennai under water on a screen inside the talks along with messages from across India. The next day, India’s official position had changed.

Environmental organizations combined forces to focus the calls of millions of people worldwide for real action at COP21. On the last day of the conference, we the people had the last word, with over 15,000 of us ignoring the earlier ban on public gatherings to congregate on the road leading to the Arc de Triomphe, holding long red strips of cloth to symbolize redlines that we won’t allow the global corporate power structures to cross.

One of the key principles of the Paris Agreement is that the nations will continue to meet every five years to strengthen their emission cuts until they reach adequate levels. It is as though the politicians, recognizing their own inability to solve the problem themselves, are inviting the people of the world to put further pressure on them in the coming years, to make sure those emission cuts finally get to what we need. And the climate movement is ready to take them up on it. In the words of 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben:

For the next few years our job is to yell and scream at governments everywhere to get up off the couch, to put down the chips, to run faster faster faster. We’ll fan out around the world in May to the sites of all the world’s carbon bombs; we’ll go to jail if we have to. We’ll push… Think of us as a pack of wolves. Exxon, we’re on your heels. America, China, India – that’s us, getting closer all the time. You need speed. It’s our only chance.

There has never been a more important time to be part of the movement. A leading environmental analyst, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, surmised that this moment “is a turning point in the human enterprise, where the great transformation towards sustainability begins.” Whether his hopeful words become a true prophecy depends more than ever on each of us, and our own commitment to drag our politicians to a world they seemingly cannot get to by themselves.

Jeremy Lent is an author and founder of the Liology Institute, which is dedicated to fostering a worldview that could enable humanity to thrive sustainably on Earth.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/COP21-is-jubilation-warranted/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.