Bees are not ordinary wildlife. They have a special relationship with human society. For millions of years bees have evolved to perform an essential role in pollinating flowers and food crops on which animals and humans depend. So they are vital to our current and future food supply. However, driven inextricably by global overpopulation and the overuse of insecticides like neonicotinoids that are harming the bees’ immune systems, bees are dying today at an unprecedented rate.

In the three following posts to the MAHB Blog I will describe first how bees communicate by a set of fascinating dances —quite remarkable in the animal kingdom! I then list the fast disappearance of bees and how we can help. Finally, I look towards the future with new technologies such as self- pollination, synthetic biology producing new insecticide bacteria, and robot bees with Artificial Intelligence.

Social Organization of the Bees

There are three kinds of bees:

1. The queen bee lays up to 2500 eggs/day. There is only one queen in a colony, which may number 60,000 bees or more. Larva destined to become a queen bee is fed royal jelly for the entire larval stage. The queen only develops from fertilized egg in the largest cells in the hive and can live up to 3-4 years.

2. The worker bees take up different jobs throughout their lifetimes. Their main function are as foragers, collectors of nectar, pollen, water, and resin. But they are also in turn guards, builders, cleaners, nurses, heating and cooling technicians[1], and scouts. Eventually, after collecting their trove they are honey makers, pollen stampers. They build complex hives with beautiful honeycombs of perfect hexagons. They accomplish great feats of navigation. They see more colors and smell more scents than humans do. They even see and use the polarization pattern in the sky which we do not. And they communicate information in a complex symbolic language without match in the animal kingdom: the bee dance.

Worker bees are all female and make up about 85% of the bees in a hive. They may live up to few months and have three life stages during which they have specific roles to fill:

a. Young workers (1 to 12 days old) clean cells, nurse the young, and tend to the queen.

b. 12 to 20 days old workers build the comb, store pollen and nectar which are brought back by forager bees. They also ventilate the nest.

c. 20 days to 30 days old workers or more are primarily foragers who supply nectar and provide the enzymes needed for converting it to honey. But only a certain percentage become foragers. Forager bees can fly at a speed of about 24 km per hour and have been known to travel more than 15 km from home on a single

3. Drone bees are male bees developed from unfertilized eggs. Unlike the female worker bee, drones do not have stingers and are not foragers. A drone’s primary role is to mate with a fertile queen, and he dies after mating.

How Do Bees Communicate? The Dances

A worker bee becomes a forager when she leaves the hive and finds a source of nectar. The forager returns to the hive engorged with nectar and pollen on her body, communicating the find to those in the hive. Her dance begins when she has attracted the attention of enough bees in the hive. She begins by spending 30-45 seconds regurgitating and distributing nectar to bees waiting in the hive.

Four different types of bee dances have been identified:

Round Dances are used for food sources less than 25 -100 meters away from the hive. The forager bee turns in circles alternately to the left, then to the right. The pattern runs in a sickle shaped path. The richer the food source, the longer and more vigorous the dance. After the dance ends food is again distributed and the dance may be repeated three times.

The Waggle Dance replaces the round dance as the food source becomes more distant and more plentiful. During the waggle dance the bee waggles her tail in a zigzag fashion to the right and to the left.

The bee runs straight ahead for a short distance, returns in a semicircle to the starting point, again runs through the straight stretch, describes a semicircle in the opposite direction and so on in regular alternation creating a figure-eight pattern. The straight part of the run is given particular emphasis by a vigorous wagging of the body (rapid rhythmic sidewise deflections). In addition, during the tail-wagging portion of the dance the bee emits a buzzing sound.

The bee runs straight ahead for a short distance, returns in a semicircle to the starting point, again runs through the straight stretch, describes a semicircle in the opposite direction and so on in regular alternation creating a figure-eight pattern. The straight part of the run is given particular emphasis by a vigorous wagging of the body (rapid rhythmic sidewise deflections). In addition, during the tail-wagging portion of the dance the bee emits a buzzing sound.

The waggle occurs on a special dance floor near the entrance to the hive facilitating quick entry and exit of foragers so as to waste no time during the foraging period in the day. Only bees with news of highly profitable sources of nectar execute the dance. Arriving back at the nest, a bee with news immediately proceeds to the dance floor, where other bees waiting for news gather around her.

Important information is encoded in the waggle dance.

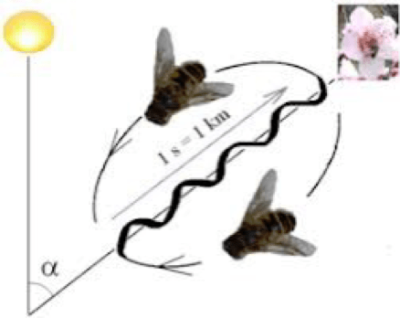

In waggling its tail following a figure-eight pattern, the bee uses the direction of the straight part of the run in the middle of the figure-eight to communicate the direction of the trove in relation to the sun. In general the hive lies in the vertical direction to the ground and the dance floor lies on a vertical plane. If the trove of nectar lies in the same direction as the midday sun, the foraging bee dances with the straight portion of the waggle dance facing the sun straight ‘UP’. If the source lies in the opposite direction of the sun, the bee dances with the straight part of the waggle dance straight ‘DOWN’. If the source, the flower, is to the right, the bee dances at the appropriate angle to the right. The angle is marked by ‘α’ in Figure 3. Modern beehives consist of a set of vertical boards enclosed in a wooden box. There is no sun and under these circumstances, gravity takes over as the sun.

The distance between the hive and this flower source is encoded in the speed of the waggle runs. The farther the target, the slower the waggle phase. For example: in 15 seconds, the bee may complete 8 to 9 circuits for a food source 200 meters away, 4 to 5 circuits for a food source around 1000 meters away, and only 3 circuits for a food source 2000 meters away. The farther the flower patch lies from the hive, the longer the dance lasts. For every additional 100 meters, the bee prolongs the dance by roughly 75 milliseconds.

The information on the richness of the source is conveyed by how long and how vigorously the bee dances through waggling of the tail and fluttering of the wings. In all cases the quality and quantity of the food source determines the liveliness of the dances. If the nectar source is of excellent quality, the forager will dance long and enthusiastically each time on returning from foraging. Food sources of lower quality will produce fewer, shorter, and less vigorous dances; recruiting fewer new foragers.

The larger the find the more excited the bee is about the location, hence the faster and longer it will waggle so as to grab the attention of the other observing bees waiting in the hive, and try to convince them. When excited she will flutter her wings to produce a vibration sound. If multiple bees are doing the waggle dance, there is a competition to convince the observing bees to follow their lead. Competing bees may even disrupt other bees’ dances or fight each other off. What a human like behavior! The longer the forager waggles –typically bees make between one and 100 waggle runs per dance– the richer the source.

The larger the find the more excited the bee is about the location, hence the faster and longer it will waggle so as to grab the attention of the other observing bees waiting in the hive, and try to convince them. When excited she will flutter her wings to produce a vibration sound. If multiple bees are doing the waggle dance, there is a competition to convince the observing bees to follow their lead. Competing bees may even disrupt other bees’ dances or fight each other off. What a human like behavior! The longer the forager waggles –typically bees make between one and 100 waggle runs per dance– the richer the source.

In general the forager bee stays on a given type of flower and returns to the hive to dump her find before going to another species of flower. In this way the scent of the source is preserved for the other bees in the hive, who sample it with their antennae. This is necessary in the case a larger contingent of bees is needed to go and collect the nectar, which may be plentiful for only a short period of time. It is useful for them to know the scent especially if the sunlight is dim.

When the bees are flying or rubbed together, they accumulate an electric charge. Bees emit constant and modulated electric fields during the waggle dance. Both these low and high-frequency components emitted by dancing bees induce passive antennal movements in stationary bees.

Arriving back from a good foraging run, a forager bee does the Shake Dance when nectar sources are so rich that more foragers are needed. The shake dance encourages these non-foragers to make their way to the waggle dance floor and observe the dances. The forager bee will move throughout the hive and shake her abdomen back and forth before the brood for one to two seconds before moving onto more non-foragers at a rate of one to 20 bees per minute.

Finally, the forager bee does the Tremble Dance when she has brought so much nectar back to the hive that more bees are needed to process the nectar into honey. Walking slowly around the nest, the dancer quivers her legs, causing her body to tremble forward and backward and from side to side. Lasting sometimes more than an hour, the tremble dance stimulates additional bees to begin processing nectar.

In the next two posts I will be sharing more information about bees. On Thursday, I will list the fast disappearance of bees and how we can help; and next week I will conclude with a look towards the future with new technologies such as self-pollination, synthetic biology producing new insecticide bacteria, and robot bees with Artificial Intelligence. Continue reading Part II and Part III.

[1] Author Note: The temperature of the hive is very carefully kept, between 32-35 ᵒC. Whenever the temperature in the hive is too high, the worker bees ventilate the hive by fanning the air out with their wings. When the temperature is too low, the workers generate metabolic heat by relaxing and contracting their flight muscles. The resulting vibration generates heat.

Gioietta Kuo has MA at Cambridge, PhD in nuclear physics, Atlas Fellow at St Hilda’s College Oxford and many years research at Princeton. She has written many environmental articles for World Future Review, and in Chinese –People’s Daily, World Environment, Magazine for the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection. She has published more than 100 articles in American and European professional journals. She can be reached at <kuopet@comcast.net.>

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/dance-bees/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.