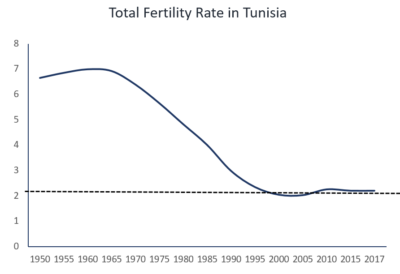

In the early 1960s, Tunisia became the first country on the African continent to significantly improve women’s status and launch a voluntary national family planning (FP) program. Today, Tunisia has some of the most progressive family planning policies in Africa, and it is the most progressive of all Arab countries in terms of gender equality and women’s rights. As a consequence, its fertility fell from 7 children/mother in the 1950’s to around replacement level by the early 2000’s, allowing Tunisia to harness the benefits of its demographic dividend.

Next in The Overpopulation Project’s ’Population Policy Case Study Series’, after Asia (Indonesia, South-Korea), the Middle East (Iran) and Latin America (Costa Rica), we turn to the continent characterized by the fastest population growth, Africa, and examine a small country in the Maghreb region.

Tunisia is one of the most progressive Arab countries in terms of women’s rights. Despite having limited natural resources, Tunisia’s recent growth and development performance have been notable relative to its geographic neighbors and other countries at similar levels of development.

Shortly after gaining independence from France in 1956, Habib` Bourguiba, the leader of the independence movement and new president, began his authoritarian regime. His undemocratic one-party rule continued for 28 years with little political opposition (1). What should we expect from a strong nationalistic president, in terms of women’s rights and modernization?

Surprisingly, Tunisia’s almost entirely Arab and Muslim population experienced rapid development in almost every area under president Bourguiba. Shortly after independence, he began a remarkable liberalization of the law, inducing social changes outstanding at the time, especially for a Muslim country. The president, educated in Paris, recognized that empowering women was essential for the development of the country. He gave women the right to vote, to remove the veil, and to divorce. Uniquely in the Arab world, he forbade polygamy and child marriage. In addition, Bourguiba made female sterilization and abortion legal (for personal reasons after the fifth child), altogether considerably improving women’s legal status in a very short period of time (2). These measures, including limiting government subsidies after the fourth child, are considered the first modern population policies in the Arab world and on the African continent. Bourguiba’s unique legislation was based on a modern interpretation of Islam, the writings of Tunisian reformers in the 1930s, and the pronouncements of Tunisian religious leader Sheikh Fadhel Ben Achour. According to these doctrines, his legislation was not contrary to the precepts of Islam; and consequently, it was generally well received by religious leaders and the public (3).

In 1962, Tunisia’s national Economic and Social Development Plan recognized the need to reduce population growth in order to achieve economic and social improvement. With the help of the Population Council, and after meeting with Asian and American FP experts who had helped set up successful programs, an experimental FP program began in 1964. National surveys from that year show that there was a strong demand from women to limit their family size, but knowledge and use of contraception were low.

The program was based on training doctors and midwives in contraceptive methods (mostly IUD and the Pill) in order to offer them in clinics and hospitals; first in the cities, then later in the countryside using mobile units. The reaction was generally positive, without significant opposition (2). Overall, this experimental phase between 1964-66 first introduced the concept of FP to the population and to health care workers, and set the stage for the national program to come.

During the fully developed national FP program begun in 1966, hospitals continued to offer free FP services, focusing on the IUD, but including the provision of oral contraceptives, sterilization, and abortion as well. In rural areas, where the health infrastructure was weak, the program relied on mobile family planning teams, later complemented by educational teams. The abortion law was further liberalized in 1973, removing earlier restrictions (limiting abortion to women with a minimum of five children). This liberal abortion law is still unique in the Arab world. The first Muslim woman physician in north Africa, gynecologist Tewhida Ben Sheikh, led the new Tunisian Family Planning Association and actively supported the program.

Despite some fears of aging at the beginning of the national FP program, the program did not change its direction. President Bourguiba did say in one of his speeches: “We must have children if we are not to become a nation of old people” (2). Still, the national FP program was extended during the following authoritarian regime of president Ben Ali, and continues today. In 2014, Tunisia had the second strongest FP effort in Africa (after Rwanda) in terms of policies, access to contraception and services, and evaluation (4).

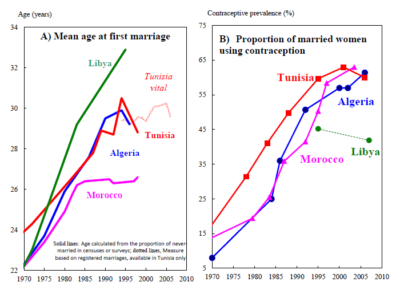

As a result of its population policies, including the focused FP program, Tunisia’s contraceptive prevalence grew from 12% to 60% in 23 years, and is the second highest on the continent today (after Morocco). The country’s unmet need for contraception is the lowest in Africa, 10.5% in 2015 (5). The total fertility rate fell from 7.2 children/women at the time of independence to replacement level in the 2000’s. One analysis argues that the majority of this decline was due to raising the legal age of marriage, to 17 for women and 20 for men in 1956 (6). The increase in contraceptive use contributed less to fertility decline, accounting for less than one-third of the decline between 1964-1969 (6). Indirectly, the improved status of women and the expansion of women’s and men’s education likely contributed substantially to the decline in birth rates.

This success served as a model, and influenced other African countries’ population policies. Tunisian family-planning experts set up four mobile teams in Niger at the request of that country’s government in the 1960’s, and held trainings in hospitals in Tunis for other African health workers. The most obvious early influence was on neighboring Morocco, with whom Tunisia exchanged senior officials, leading to the launch of the Moroccan FP program in 1966.

In recent years, Tunisia has been actively pursuing social change in an attempt to benefit socially and economically from its declining birth rates. Still, the exploitation of the demographic dividend is far from perfect. The unemployment rate of the large working age population is high, around 15.5% since 2015. There are also shortcomings in the implementation of reproductive health policies, and more to be done to achieve gender equality. For example, discrimination against single women seeking contraception and abortion is still common, largely due to societal taboos around extramarital and premarital sexual relations (8). The latter is a widespread issue, as we pointed out in the case of Indonesia, and must be addressed.

Tunisia now has a chance to take advantage of slowed population growth in addressing its environmental issues. The major problem in Tunisia, as in the rest of northern Africa, is desertification. Overgrazing, along with deforestation, soil erosion, and overuse of limited freshwater supplies, all drive desertification. The same factors drive salinization and siltation of the soil, as well. Halting population growth and the associated human pressure on the land would aid in the fight against desertification and the related decrease of arable land.

How did a “dictator” such as Habib Bourguiba develop such a far-sighted population policy? The president’s answer to this question in 1966 was: “J’ai de baggage dans ma tête” (“I have got a lot of brains”) (2). It is hard to say from this answer what his actual motivation was. Maybe his education in Paris inspired his support for empowering women, maybe the successful Southeast Asian FP programs that catalyzed economic development inspired him – we don’t know. But whatever the reason, we hope that there are many more leaders in countries undergoing rapid population growth who “have got a lot of brains” and recognize that unsustainable population growth undermines social, economic and environmental sustainability. The Tunisian example illustrates that the right population policies, such as increasing the legal age of marriage and access to free contraception, can effectively reduce fertility rates, thus limiting population growth while empowering women at the same time.

References

- Derradji A-R. Tunisia: Form Bourguiba’s Era To The Jasmine Revolution; Fall of Ben Ali. ADAM Akad Sos Bilim Derg. 2016;1(2). https://dergipark.org.tr/download/article-file/230570.

- Robinson WC, Ross JA. The Global Family Planning Revolution : Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs. World Bank; 2007.

- Richard H. Curtiss. Tunisia’s Family Planning Success Underlies Its Economic Progress. Washington Report On Middle East Affairs. https://www.wrmea.org/1996-november-december/tunisia-s-family-planning-success-underlies-its-economic-progress.html.

- Track 20 Project. Family Planning Effort Index (FPE). http://www.track20.org/pages/data_analysis/policy/FPE.php. Accessed July 13, 2019.

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Trends in Contraceptive Use Worldwide 2015 United Nations.; 2015.

- Lapham RJ. Family Planning and Fertility in Tunisia. Demography. 1970;7(2):241. doi:10.2307/2060414

- Ouadah-Bedidi Z, Vallin J. Toward replacement level : unexpected recent changes in maghrebian fertility. In: XXXVII IUSSP International Population Conference; 2013.

- Amroussia N, Hernandez A, Goicolea I. Reproductive Health Policy in Tunisia: Women’s Right to Reproductive Health and Gender Empowerment. Helath Hum Rights J.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org