Our unquestioning attitudes about dominion over the rest of nature are strikingly similar to the unquestioning attitudes held by dominant cultures throughout history about their dominion over the rest of humanity. –Speciesism in Biology and Culture: How Human Exceptionalism is Pushing Planetary Boundaries, p.11

Geoff Holland—In your book Speciesism in Biology and Culture you say, “Species are collections of twigs on the evolutionary tree of life that are considered different enough from other collections to be so designated—basically different ‘kinds’ of organisms”. If that’s how we’ve been designating and categorizing all the various lifeforms on Earth for much of recorded history, why do we need to rethink how we view nature and the biodiversity of life on Earth?

Brian Swartz–It will be helpful to contextualize the quote because it is part of a complete paragraph that goes on to say: “…species are arbitrary stages in a continuous evolutionary process.” Remember that for most of recorded history, biodiversity has been viewed through a creationistic lens (e.g., baramins, kinds, species, etc.). Using modern evolutionary tools, the question becomes: We often hear that biodiversity is about species, but are they uniquely real things in the natural world that are different from and more special than genera, families, kingdoms, etc.? What are the implications if they are not more special than other groups?

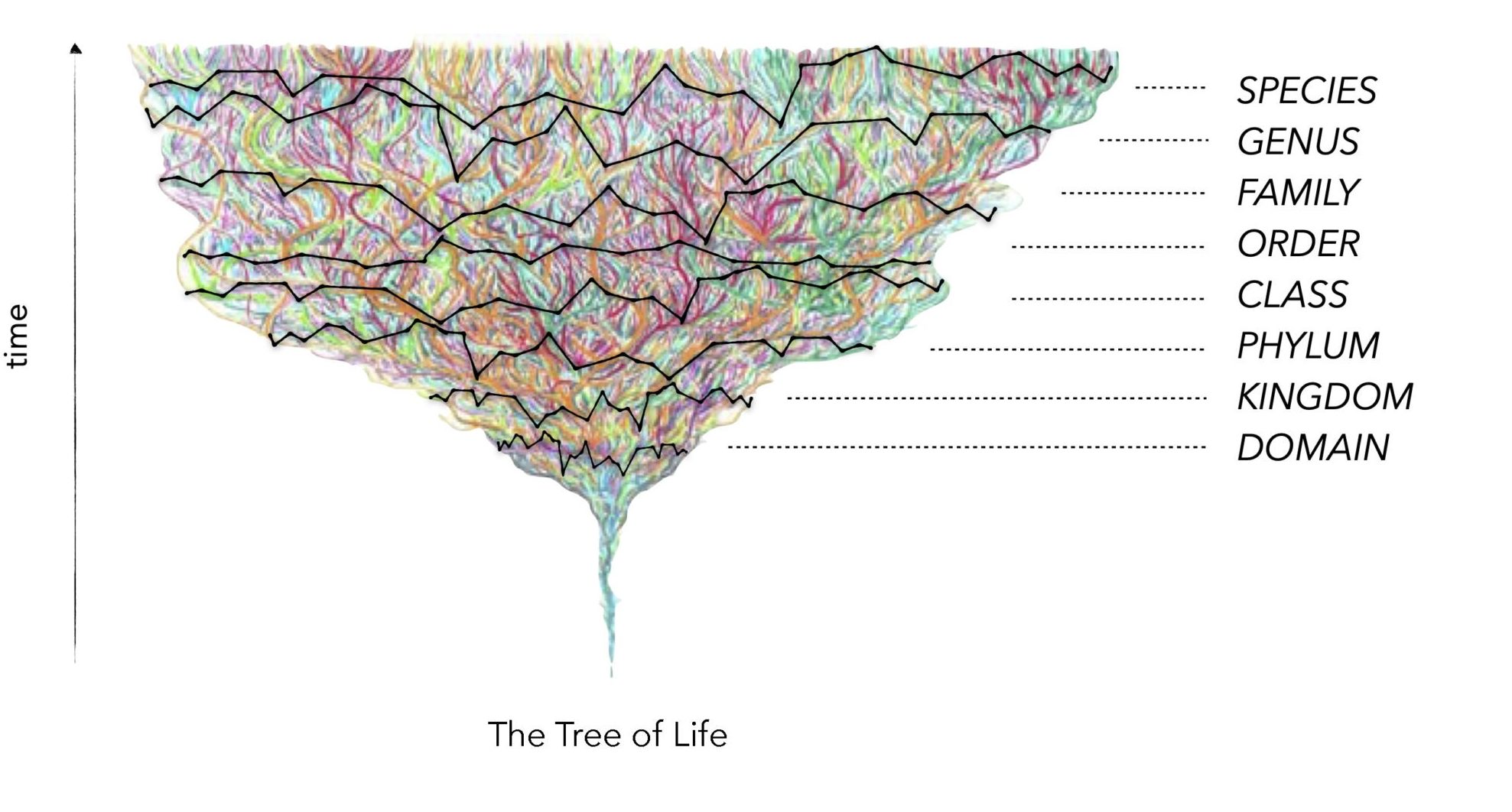

Species are arbitrary cross-sections at irregular depths that cut across the tree of life. See Figure 1: a species of amoeba means something different than a species of plant, animal, or anything else. Species are non-corresponding levels, like how genera and families irregularly transect branches. There is nothing uniquely real about the species level that transcends lineages. However, this inconsistency changes when you focus on lineages—ancestor-descendant connections united by space and time. The web of life comprises these ancestor-descendant pairs, and genealogical descent unites all lineages. A lineage of one branch means the same thing as a lineage of another, which differs from taking hedge clippers and inconsistently cutting branches while thinking that snipped tips of variable length (i.e., species) are equivalent.

The implications get us straight into speciesism, the dual proposition that a) species are uniquely real and b) one or more species are superior to all others. Each tenet falters under scrutiny. We just spoke about how species are human constructs. Regarding superiority, it is clear that most humans see themselves as undeniably superior to other forms of life. This worldview scales to a planetary ego and sets into motion much about how we behave. Things go bananas when we consider the consequences of this behavior. What problems on Earth are not downstream of those consequences? From climate change and biodiversity loss to pollution and the future of life, it all extends from human perceptions and behaviors as a globally dominant lineage.

Despite personal opinions, the proposition for superiority struggles on the evolutionary stage because single lineages are not superior as entities. Specific traits may be superior as trait-vs-trait comparisons (e.g., vision in eagles vs. humans, intelligence in humans vs. octopuses). However, evolutionary success is about diversity, the persistence of diverse lineages, and the environmental context in which this is relevant. A better “trait” (e.g., intelligence) does not necessarily correspond to diversity and persistence. Superiority, in an evolutionary sense, is a bit like financial investing. “Past performance does not guarantee future results.” Success is only as good as current performance in current markets. This is because adaptations are to prevailing environments, and lineages are affected by the harsh filters of a changing world.

A verdict on superiority is therefore premature. What does it mean to say we are better than other lineages unless calibrated by a record that exists independently of us? We can try changing criteria to scratch an egotistical itch, but the metrics unravel to reveal a construct deeply intertwined with human biases rather than grounded in evidence.

To claim superiority, one might point to our technological advancements, complex societal structures, or ability to manipulate the environment to our advantage. Indeed, we are the lineage that changes things! However, this is a narrow lens that fails to encompass the myriad ways in which other lineages excel. The sheer diversity of life on this planet and the panoply of adaptations and strategies all underscore a kind of excellence humanity does not monopolize. We differ in ways we think are important, which predisposes us to overlook “different” and subjectively land on “better.”

The notion of superiority is also inherently fluid, subject to the shifting sands of time and environmental change. In the grand scheme of history, humans are relatively new. Our perceived superiority, built mainly on the surge of mind-blowing technology, may not withstand stress testing.

You ask why we need to rethink how we view nature and biodiversity. The answer to “need” depends on the goals that we create for ourselves. Life and Earth are at a tipping point, and social narratives (self-perceptions, stories, and behaviors that result) will influence how we tip. It is certainly in our interest to prioritize humanity, but it is time to correct course. As an evidence-based narrative, stepping back from a naïve exceptionalism is a strategic path toward an abundant future.

For example, AI is upon us, and we are racing into the future of an exponential age, applying cultural tools and taking control of our evolution. We are leveraging AI to grant us superhuman abilities. With the likely arrival of artificial general intelligence (an all-purpose form of artificial intelligence) by the end of the 2020s, we will direct AI toward the most significant problems of our time. Pair this with the fact that you already have a brain extender (cell phone) and are increasingly merging with cultural tools, and it is clear that AI exists at the nexus of technology, culture, and biology.

For the first time in history, humanity is creating new lineages that are synthetic AND biological. We are further directing a form of superhuman intelligence toward conquering aging, pollinating space, and buttressing our resistance to extinction. If we get to a point where culture increases human diversity while decreasing the probability of death and extinction, we will have done something “successful” in the most objective biological sense.

In the natural world, the game is to diversify. The most successful lineages (e.g., insects, bacteria, etc.) have done precisely this. Yet there remains only one major branch on the human tree of life. It’s us. All the rest are extinct. If technology facilitates diversification and increases extinction resistance, you might think there is space in the human story for “better” and not just “different.” The problem is that we are among a spectrum of organisms who have already solved these problems. Other life forms can regenerate themselves at the cellular level, reprogram biological ages, and be globally resistant to extinction. Extinction resistance has been one of the most dominant evolutionary trends over the last 541 million years. Such groups accomplish these feats with cultureless biology, so if humans are successful, we will have done it with biology and culture together.

In essence, to say that humans are superior to other lineages ignores the complexity and richness of life. As we stand at a pivotal juncture in our evolutionary journey, we are poised to apply culture to direct our biological future. It is incumbent upon us to acknowledge the intrinsic value of other life and our interdependence with it. Moving away from a narrative steeped in superiority can be a pathway for achieving our collective goals.

GH—You also say, “Speciesism is to species as racism is to race. The tenets of both are baseless on all grounds.” Can you elaborate on that?

BS–This is a good question. To build it out, let’s recognize that speciesism analogizes with racism because species analogize with races. Each unit is a human construct. Specifically, speciesism is the view that a) species are uniquely real, and b) one or more species are superior to others. Racism similarly carries these precepts: a) races are uniquely real, and b) one or more races are superior to others.

Yet there is nuance we must acknowledge: species realism describes the view that species are uniquely real, whereas racialism sees races not as societal constructs but as branches on the human tree of life. One can be a racialist without being a racist (“races are uniquely real but none are superior”), just as one can be a species realist without being a speciesist (“species are uniquely real but none are superior”). However, like with speciesism, embracing *superiority moves you from being a racialist (“races are more than cultural constructs”) to being a racist (“at least one of these races is better than the others”). In this way, the speciesist and racist both accept the unique reality of each unit and the proposition that their units are superior.

However, speciesism and racism are indefensible for basically the same reasons. Broadly, species are irregular cross-sections of the tree of life, and races are not distinct branches on the tree at all. They are both cultural constructs. Similarly, no single construct is superior to a different one for all the reasons in the previous question.

Let us consider an example that puts the evolutionary piece in perspective. No branches on the human tree of life correspond to “Asian people’‘, “white people”, etc. Evolutionary trees are about lineages, from their tips to the base, which capture varying degrees of relatedness. The more closely in time you share a common ancestor with someone, the more closely related you are. Comparatively, cultural races are spread across various branches and fail to sample complete lineages. For example, by recency of common ancestry, I am more closely related to cousins in Morocco (non-white people) than I am related to other people who look white. We can create cultural groups with racial names, but this doesn’t mean those groups are lineages. In this case, someone who looks white (me) is more closely related to non-white members of the human population. If races are biological categories (lineages), why would someone more closely related to non-white people be in a separate group (white people) merely because their skin tone varies? The root point is about shared common ancestry. That is what determines relatedness, not the thousands of slight continuous variants that make us look, think, and appear similar or different.

Given this, skin tone is as much a distraction as hair color or texture in diagnosing group membership. Some traits may correlate for known biological reasons, but this doesn’t mean they adequately diagnose and distinguish one lineage from another. At this point, many traits become superficial to recognizing human lineages and, consequently, map to contrived cultural/social categories, not biological groups. From here, we can distance ourselves from the hypothesis that these social groups map onto the tree of life.

This distance reveals that races are social constructs and racism is indefensible. Given a) the fractal nature of evolutionary trees (groups nested in groups), b) the web-like nature of gene flow (lineages do not just split, they also merge), and c) the arbitrary boundaries around racial groups, the racist will eventually be more closely related to members of their outgroup than to members of their contrived ingroup. At this point, the racist must question their sense of superiority. How can hate be justified when discriminating against your kin based on noisy traits that weakly map across the tree of life?

People will always invent reasons to discriminate and justify ingroup/outgroup thinking, but the evidence does not support this based on perceived race.

Similar to races, species are cultural constructs. Like all other taxonomic levels, the species rank samples the tree of life and cuts across its branches at irregular depths. There is no evidence consistently applied to substantiate why this level transects one lineage at one length and a separate lineage at an equal or different length.

Whether it is reproduction, anatomy, behavior, etc., species concepts are about as variable as the traits visible across the tree of life. People think of species as lines in the sand that transect lineages at differing depths but lack a consistent unified process to substantiate this level in different groups. Comparatively, ancestor-descendant pairs (lineages) comprise the tree of life and capture the same root processes irrespective of the groups under consideration. A lineage of bacteria is a continuity of ancestor-descendant pairs, just as a lineage of plant, fungus, or animal.

Therefore, like the racialist, the species realist proposes that species are uniquely real biological things, more special than other levels of categorization. They acknowledge the arbitrary nature of higher taxonomic ranks yet hold onto the species rank as the one true level, like a fundamental unit of biology. The problem is that this view breaks down when you look across the tree of life. Variation among lineages forces us to move past our animal-centric concept of how biology and evolution work.

Irrespective of how cultural categories emerge, inconsistently sampling diversity creates a mismatch between the groups you think you’ve found vs. the lineages that actually exist. If you aim to move beyond social constructs and ground a worldview in an evidence-based framework, then focusing on lineages is the way to go. Mapping social groups onto the tree of life reveals the indefensibility of species and races as unique biological units while undercutting perceived superiority. At this point, each tenant for each “-ism” quickly falls into the background of an alternative biological presence. We are all each other’s relatives, none superior or inferior by proxy to external measures of diversity and persistence on an ecological stage.

GH—Humans have been a distinct lineage for something like 300,000 years. For about 95% of the time humans have been on Earth, we were nomadic hunter-gatherers, a.k.a. Stone Age cavers; clans whose survival depended on cooperation and caring for each other. How did humans view the rest of the natural world during that pre-historic era, and is that reflected by the indigenous people here now?

BS–For the majority of human history, we lived as hunter-gatherers. This lifestyle required a deep understanding and connection to the natural world. Our livelihoods depended on knowledge of animal behavior, plant cycles, weather patterns, and more. This relationship with nature fostered a worldview that saw humans as part of nature, not separate or superior to it. Many indigenous cultures today reflect this ancient worldview. They often deeply respect the natural world, seeing themselves as stewards of the land rather than its owners. Their practices and beliefs often emphasize the interconnectedness of all life and the importance of maintaining ecosystems.

Modern industrialized societies have largely lost this connection to nature. Most individuals no longer depend on a direct understanding of the natural world. Instead, we rely on complex systems of agriculture, industry, and commerce. This reliance has led to a sense of separation from nature and, in some cases, a belief in human superiority. If we see ourselves as superior, it’s easier to justify exploiting resources for our benefit. Recognizing our place within the tree of life can foster a more sustainable relationship with the world around us. To challenge speciesism and create a more prosperous future, we might look to our hunter-gatherer ancestors and indigenous cultures for inspiration.

GH—A warrior class emerged when humans began farming and living in permanent settlements. That led to cultural hierarchy and male dominance that spread with humans to every corner of the planet. How did those cultural changes impact how humans viewed each other and the natural world that provided their survival needs?

BS–With the advent of agriculture, humans began to settle in one place, leading to the development of larger, complex societies. The shift to agriculture fundamentally changed our relationship with the natural world. We began seeing nature more as something to be controlled and manipulated for our benefit. This shift allowed the accumulation of resources, facilitating complex social hierarchies and gender inequality. Inequality could lead to dehumanization, where individuals lower in rank were viewed as less valuable. These historical shifts have had lasting impacts that we feel today.

Modern societies still grapple with issues of inequality and our relationship with the natural world. Understanding our history can help us address these issues and work towards a more equitable and sustainable future. However, let us remember that humans are still social primates, and the nuances that connect social behavior with this psychology are an ongoing area of research. It would not surprise me if a global attitude of dominance extends from predispositions as social animals that scale to the planet writ large. As with all aspects of behavior, the best answer to how culture affects worldviews lies at the intersection of nature, nurture, timescale, and context.

GH—As the recording of history began during the agricultural era, new forms of organized religion emerged, structured on the male-dominant cultural model. Christianity and Islam are two very influential traditions built that way: men in charge, men making the rules, and women subjugated and reduced to a form of property. It’s still the predominant form in the 21st century. How has male-dominant religion shaped the dysfunctional world we see playing out 24/7 in the media these days?

BS–Many of the world’s religions emerged in patriarchal societies, and this is reflected in their doctrines and practices. These religions often promote a hierarchical view of the world, with “God” at the top, followed by men, women, other animals, and the rest of the natural world. This hierarchy reinforces the idea of male dominance and human superiority over other organisms. These religious traditions have had a profound influence on societies. We see this influence in many aspects of culture across law, politics, economics, education, social norms, and family life.

Male dominance in religious traditions often goes hand in hand with speciesism. If human men are superior to human women, then it’s a small step to viewing humans as superior to non-humans. This worldview can lead to toxic attitudes and behaviors that harm everyone. If we regard humans as the pinnacle of creation, it’s easy to justify the exploitation of other organisms for human benefit. This belief can—but need not—lead to a lack of concern for the welfare of non-human life or environmental health. Do you dominate the world, or are you a steward? Increasingly, many religious movements are highlighting the latter over the former.

The media often covers conflicts over religious beliefs, gender inequality, and human rights abuses that at least partly share parallels with the influence of male-dominant religious traditions. Yet media plays a crucial role in shaping public perceptions. It often focuses on conflict, controversy, and sensationalism, amplifying these issues’ visibility.

As best I can see, our ground truth is less dysfunctional than what the media amplifies. There are data, informed interpretations of data, and leveraged variations that target the emotional centers of brains to facilitate group thinking and undercut our mental faculties. Defending your prefrontal cortex from emotional hijackers is one of the most strategic options on our table. Seeing the world objectively and channeling this to inform decisions based on subjective goals is a powerful tool to change minds and influence behavior. What are the purposes we can rally around? That’s where story and narrative enter the picture. If we can agree on that (e.g., a sustainable future of abundance), navigating that trajectory is simply a matter of details.

GH—Our longstanding cultural dogma built on “blind faith” has left the majority of humans believing that we are above and superior to nature, that we should “go forth and multiply,” and that we humans are obligated to exploit nature with no concern for consequence. How is that revealed in how humans have long categorized and diminished other lifeforms with “culturally prejudicial” labels?

BS–Many cultural and religious traditions promote the idea that humans are superior to nature. This belief can be traced to religious texts instructing humans to “go forth and multiply” and have dominion over the Earth and its creatures. This worldview positions humans as separate from and superior to the natural world, which can lead to exploitative attitudes and behaviors. Yet challenging prejudiced labels and beliefs can foster a more effective relationship with the natural world.

The belief in human superiority can come through how we popularly categorize and label things. For example, we commonly label animals based on their usefulness to us (e.g., livestock, pests, pets, weeds). Labels are often a form of cultural judgment where we impose human-centric values and perspectives onto other things. Just as we’ve historically used labels to marginalize and devalue certain groups of humans, we also use labels to marginalize and diminish different lineages (e.g., animals, mammals, primates, and apes). Humans are members of each group, even though we react emotionally to being called an animal or ape. These are just lineages! Some animal groups are more closely related to humans than to other animals. This nested pattern of relationships (groups subordinate to groups) means that group names apply to all members within each subset of the tree of life. We may not like thinking of ourselves as animals or apes, but this reaction reinforces just how special we think we are. The tree of life is not a moral judgment of your character. It is a “what is” among patterns in nature, so we may as well celebrate being family instead of diminishing the value of other life forms.

GH—Please expand on the concept of speciesism and what your analysis says about how we should be viewing the tree of life– and what it tells us about how we should be relating to nature and all the other lifeforms with whom we share our home, planet Earth.

BS–“Should” questions are slippery propositions in a world based on evidence. For example, there are no right or wrong behaviors, such as telling someone their “behavior is incorrect.” What does incorrect behavior even mean, and what “should happen” instead? I realize that this language is often used in a moral sense, meaning that someone’s behavior is ethically objectionable or culturally inappropriate, even if not empirically false. Words become slippery when used imprecisely in a landscape of similar terms with different definitions when context varies.

This style of question slides effortlessly into the naturalistic fallacy, thinking that “natural is good” due to confusing “what is” vs. “what ought to be”. What ought to be is a very loud SHOULD. Such desires direct the theatre of human history, but how can we reflect on how the future “ought to be” we want to make? Within the framework of goals, we can say that we should or shouldn’t do something because our actions undercut desired results. However, if not grounded pragmatically, “should” thinking can quickly become ideological.

Suppose our goal is to guide humanity toward a sustainable future. In that case, we should view the tree of life as an evolutionary and ecological network that forms the basis of humanity’s life support system. It turns out that’s what it is. Suppose our goal is to dodge extinction, persist, thrive, and even diversify into the future. In that case, we should view nature and other life forms as something to curate, nurture, and establish healthy relationships with because our future depends upon this. The natural world is amoral and detached from human “shoulds.” It is the overarching “what is” that subsumes every anthropocentric “ought to be.” Nature will be here irrespective of us, even if we suffer alongside it. Given our goals, the character of this relationship should move us to “accept the things we cannot change, the courage to change the things we can,” and the ruthless drive to test our assumptions and critically evaluate the difference.

GH—Roughly half of all of humanity is gender female. Women have had little or no cultural voice for much of our written history. That all began to change in the 19th century with the suffrage movement. These days, women are claiming more and more of the natural equal rights to which all humans are entitled. As a biologist, does the likelihood of women having gender-equal voices in cultural scale decisions give you hope for a future where humans embrace their proper role as caretakers of the natural world we depend on?

BS–Gender equality is a matter of justice and diversity. In nature, (bio)diversity is a crucial driver of resilience and innovation. Similarly, diverse perspectives can lead to more innovative solutions and more robust decision-making in human societies. We can benefit from a broader range of experiences, ideas, and approaches by including more voices. For example, in many cultures, women are heavily involved in managing natural resources like water, forests, and biodiversity. Women also tend to express higher levels of concern for the environment and support for environmental protection. Therefore, gender equality could strengthen our collective capacity to care for the natural world.

The tension with speciesism parallels the struggle for gender equality. Both involve challenging deeply ingrained beliefs about hierarchy and superiority, and both require us to recognize and respect the intrinsic value of all beings. By including more women’s voices, we can bring new perspectives and insights to solve the most significant challenges of our time. We can better use our wisdom and creativity by ensuring women have strong voices in decision-making. This choice could develop more effective strategies for environmental and technical challenges. Harking back to the previous question, I can say that if our goal is to foster a more sustainable relationship with the natural world, promoting gender equality should be a crucial part of our strategy.

GH—Techcast is one of several blogs forecasting that the internet and social media will soon turn much of humanity into a form of “collective consciousness.” How could that impact the spread of a mote of understanding like your work defining speciesism?

BS–The internet and social media allow the rapid dissemination of information and enable people worldwide to engage in discussions and debates. If the concept of speciesism were to become part of our collective consciousness, it could lead to greater recognition of the values (even rights) of non-human organisms and to changes in law, policy, and practice. That would be a powerful tool for promoting a more equitable and sustainable relationship with the natural world. The exchange of ideas offers an opportunity to shift paradigms on global issues. We can foster a deeper appreciation and respect for our place within nature, nudging societies toward more effective practices.

By leveraging technology, our mote of understanding could then pave the way for more enlightened behaviors. In the digital age, the sphere of influence of such a mote can be immensely expanded. However, navigating the waters of online discourse requires a discerning approach to overcome the pitfalls of misinformation, polarization, and echo chambers. Here, the Dunning-Kruger effect presents a significant challenge; many individuals with limited understanding of complex issues tend to overestimate their knowledge and expertise, often propagating mis/disinformation.

Fulfilling a culture of humility, critical thinking, and evidence-based reasoning is imperative to counteract this. Educational initiatives, both formal and informal that emphasize the cultivation of these skills would encourage individuals to evaluate information and remain open to changing their perspectives in light of new evidence. It is okay to celebrate our ignorance, especially when it gets us on track in a landscape of evidence that informs effective decisions. Collaborative platforms that facilitate constructive dialogue and the exchange of ideas could serve as potent tools, bridging gaps in understanding while mitigating overconfidence and guiding actions amidst data that are always incomplete.

GH—Do you see a day when the longstanding cultural momentum that has defined speciesism will give way to a transformative era in which all life forms are accepted as valued parts of the web of life?

BS–This is a good question. I think we can get most of the way there. Humans care more about other organisms we identify with as animals because we are closely related. It is a direct proportionality because humans lack free will. There will always be bias in how we think, feel, and act due to our evolutionary and neurophysiological wiring. However, the question becomes how we can 80/20 this project and identify the proverbial 20% of inputs that create 80% of results. That will get us most of the way there because, with enough leverage, a 100% overhaul is unnecessary. The strategy is about creating a minimum effective dose that can begin to move the needle and effectively target our goals. There will always be outliers; not everyone will be on board with every issue. Yet suppose enough people see and behave in particular ways while rallying around a new story. In that case, we can engineer a vehicle that generates momentum and propels us to a future we envision. At the heart of this vehicle is an engine called “story” and “narrative” that people must want to create. Success is about moving beyond the myopia of a scarcity mindset. What does your abundant future look like, and how can you get there while creating a net positive world?

Dr. Brian Swartz is the lead author of Speciesism in Biology and Culture: How Human Exceptionalism is Pushing Planetary Boundaries, with Prof. Brent D. Mishler. Brian is a former postdoc at The University and Jepson Herbaria of the University of California at Berkeley (Department of Integrative Biology, Anthropology, History, Berkeley Law) and Stanford (Center for Conservation Biology, the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere). His research focuses on speciesism and the global consequences of human self-interests. This includes fostering positive social and environmental outcomes that support a prosperous future for life on Earth. To this end, he works with a diverse network of entrepreneurs, artists, inventors, and investors who hold a similar vision for the future. These collaborations reach across health, medicine, AI/ML, XR, quantum computing, ecology, and energy. His greatest asset is his ability to connect with others on a human level and cross-pollinate thinking with interdisciplinary teams. Brian was trained at Cambridge, Berkeley, Stanford, Harvard, Penn, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. His hobbies include biking and running mountains, and adventuring magically in Merino wool.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.