All photographs © Stephen Gorman

“Everything is connected through our common atmosphere, not to mention our common spirit and humanity. What affects one affects us all…The future of Inuit is the future of the rest of the world — our home is a barometer for what is happening to our entire planet.”

— Sheila Watt-Cloutier, Nobel Peace Prize Nominee and former chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference

Inuit family Traveling Over the Sea Ice, Qaanaaq, Greenland, 2017.

©Stephen Gorman 2017

Inuit call the vast Greenland Ice sheet Sermersuaq, which means “The Great Ice.” When The Great Ice melts, it will raise worldwide sea levels by more than twenty feet, adversely affecting the entire planet and dramatically changing the lives of every person on Earth.

The melting of The Great Ice is well underway and may be irreversible. As the Arctic warms and the sea ice disappears, the effects are already being felt, and its inhabitants – both human and animal – confront a precarious future.

Everything in the Arctic food chain, from microscopic invertebrates to marine mammals to human beings, depends upon the continued existence of the ice. Yet scientists warn that the entire ice-dependent ecosystem will collapse if the melting continues. Without sea ice, seals can’t rest, eat, and bear their pups. Without ice, polar bears can’t hunt seals, and they face extinction. And without ice, Inuit hunters cannot travel in search of game.

Monument to Infinite Growth, Kaktovik, Alaska, 2017.

©Stephen Gorman 2017

Indigenous people across the Arctic – the Inuit of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland – still depend heavily on subsistence hunting to put food on the table. In a region where imported food prices are exorbitant, climate change has made subsistence hunting less reliable and more dangerous. Once-stable sea ice is now breaking apart under the feet of Inuit hunters and their sleds.

For thousands of years, the Inuit have lived with a deep and sensitive understanding of their frozen environment. To this day, hunting remains central to Inuit identity not only by providing food security but also by strengthening community and interpersonal relations and by maintaining the powerful bond between the people and their surroundings. The Inuit culture evolved in an Arctic ice environment, and without sea ice, without the means to travel and hunt, and without polar bears and seals, traditional Inuit life faces tremendous challenges.

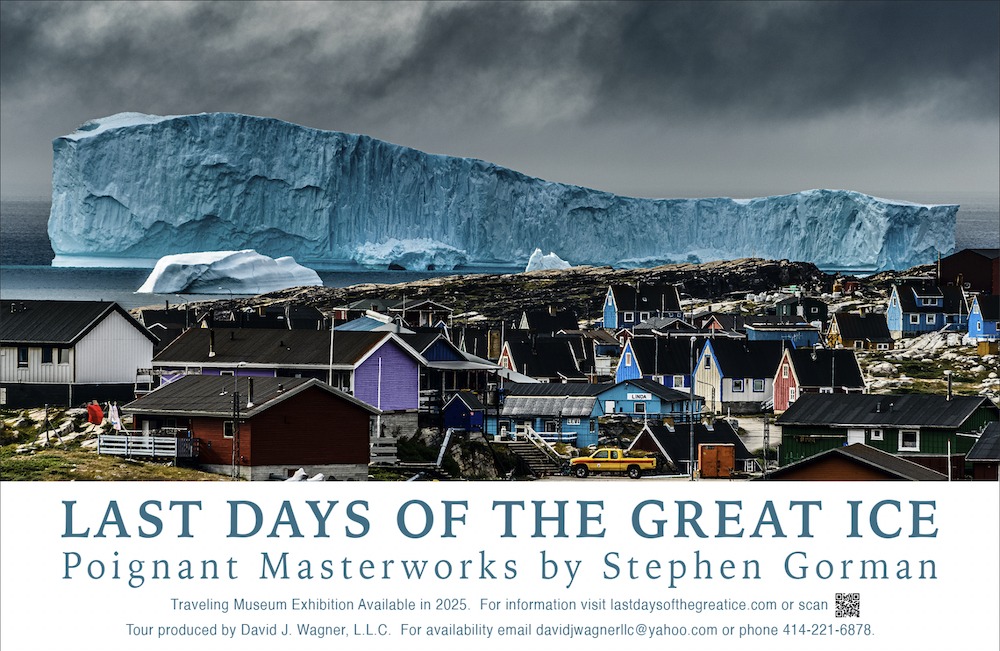

Massive Iceberg Looming Over Qeqertarsuaq, Greenland, 2014.

©Stephen Gorman 2014

As we enter what may be the last days of The Great Ice, the powerful, amorphous forces causing the collapse of the Arctic ecosystem seem unstoppable. The industrialized world has all but severed its ties with the natural world – has lost the intense affinity we once had with our life support systems – and the resulting lack of personal as well as cultural knowledge about nature undermines our ability to take any meaningful action to save the planet and save ourselves. Those of us in the industrialized world are committed to a way of life that assumes perpetually increasing consumption of finite resources forever supported by new – though increasingly unknown – technologies. We proceed in the blind faith that modern science and techno-wizardry will enable us to defy physical limits. It is clear that this model is unsustainable and has led to our current environmental crises, including the last days of The Great Ice, but we don’t know how to change course.

Ironically, after centuries of exploitation, modern industrial society must now turn to traditional indigenous peoples to show us how to save ecosystems critical to the earth’s health and how to defend undeveloped portions of the planet from the developed world’s insatiable appetites.

Avoiding the last days of The Great Ice will require industrial society to make a rapid behavioral pivot. Like the Inuit, we must find a way to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It will be hard, but we have trusted guides to show the way. We aren’t required to actually become Inuit to take advantage of their wisdom and knowledge. We simply need to follow their example.

Inuit presents us with an alternative view of the natural world, together with a different concept of humanity’s proper role in the environment. We can adopt the Inuit connection with nature and their understanding of the relationship between all living things – the belief that humans are tied to the earth in a circle of reciprocity. Like the Inuit, we can once again see ourselves as a part of nature, not separate from it.

Terminus – The End of the Frontier Myth, Kaktovik, Alaska, 2017.

©Stephen Gorman 2017

For millennia Inuit have thrived in the most challenging environment on earth by strictly observing traditions and rules of conduct and by maintaining a responsible attitude towards the use of natural resources. For thousands of years, their very cultural and physical survival has depended upon sustaining and nurturing the biodiversity and productivity of their home. The rest of us can do the same. In their arctic homeland, the Inuit show us what must be done, no matter where we live or how far from the ice we are.

For the Inuit, the Last Days of the Great Ice cannot be summed up as a crisis of misguided laws, or failed environmental policies, or feckless administrations; and it will not be solved by politicians, scientists, technical innovators, or governments. The Last Days of the Great Ice is a cultural predicament that can only be managed by all of us acting together, making a monumental shift in our most deeply held beliefs so that we can see the world as Inuit do – not as a storehouse to be raided until the riches run out – but rather as a precious home to be nurtured and cherished and passed on undiminished to future generations.

Stephen Gorman on Expedition at the Bylot Island Floe Edge in the Canadian Arctic 450 Miles Above the Arctic Circle.

Stephen Gorman is an internationally recognized photographer and best-selling book author. His work focuses on how cultural values and national mythologies shape our relationships to the world we live in and the diverse societies with which we share it. Gorman is the author and photographer of books including The American Wilderness: Journeys into Distant and Historic Landscapes, and Northeastern Wilds: Journeys of Discovery in the Northern Forest. Arctic Visions: Encounters at the Top of the World was commissioned by the Inuit of Nunavik and won the Benjamin Franklin Award. Throughout his career, Gorman has worked on cultural and environmental assignments for leading periodicals such as National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Audubon, and Sierra. His latest exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum, Down to the Bone, was a collaboration with beloved The New Yorker artist Edward Koren, and was a response to the global environmental and climate crisis.

LAST DAYS OF THE GREAT ICE – Poignant Masterworks by Stephen Gorman is a traveling museum exhibition comprised of 30 iconic, large-format photographs depicting Arctic people, built environments, snow and ice, landscapes, seascapes, and wildlife, taken by photographer Stephen Gorman between 2005 – 2018, to document the impacts of the global environmental and climate crisis. The exhibition is available for display in 2025 (the 35th Anniversary Year of ICARP, iasc.info).

LAST DAYS OF THE GREAT ICE is circulated by David J. Wagner, L.L.C.

This article is part of the MAHB Arts Community‘s “More About the Arts and the Anthropocene”. If you are an artist interested in sharing your thoughts and artwork, as it relates to the topic, please send a message to Michele Guieu, Eco-Artist and MAHB Arts Editor: michele@mahbonline.org. Thank you. ~