In this age of superior environmental awareness, when mass media and virtual reality are ostensibly supposed to make us smarter in our knowledge of the natural world, consider this paradox: One of the most famous and widely-circulated wildlife photographs ever made is an image that most members of the Millennial generation probably assume is a product of digital manipulation.

The truth behind Thomas D. Mangelsen’s iconic Catch of the Day is exactly the opposite and that’s precisely what gives it extraordinary cachet. Mangelsen’s photograph capturing the exact moment that a spawning sockeye salmon in Alaska leaps upstream into the awaiting jaws of a large hungry brown bear, is “all wild.”

The engaging masterpiece is not the result of keyboard legerdemain but painstaking old-school tradition. Here a noted American photographer methodically put himself in the right place at the right time—an exponent of Mangelsen’s life-long immersion in untamed and sometimes hostile environments.

Does it matter that nature photography reflect the truth of its subjects? Should a portrait of a real wild animal possess more potential meaning for a viewer than one which is artificially choreographed using a paid model and shot by a photographer who may not have had any tangible physical contact with nature? Indeed, at a time when “alternative facts” are running rampant, when science is under siege and art museums are struggling to remain relevant, can photography cause us to stop and think about the real state of planet earth?

These are just a few of the visual and philosophical questions that, by design, figure prominently into a new traveling museum exhibition, A Life in the Wild: The Photography of Thomas D. Mangelsen set to debut in 2018.

A Life in the Wild features more than 40 of Mangelsen’s large-format “legacy” images selected from a portfolio amassed over the last five decades and through his travels to all seven continents.

It’s a stimulating mix of imagery, spanning his signature pieces widely recognized by the public and his award-winning pictures singled out for elevating public awareness about topics ranging from the global poaching crisis, to animals perched on the edge of extinction, the consequences of climate change, and the dramatic tale of a famous grizzly bear mother dwelling in his back yard.

This summer as part of its 30 anniversary celebration, the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming—located near the boundary of Grand Teton National Park—is displaying the dazzling photographs of Mangelsen’s friend Joel Sartore, who, like Mangelsen, has contributed photographs to National Geographic over the years. Next autumn, in 2018, the same museum will feature Managelsen’s A Life in the Wild.

Adam Duncan Harris, the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s senior curator in charge of exhibition selection, says the work of each shooter complements each other and yet provides dynamic fodder for having a societal discussion.

In Photo Ark, Sartore’s images highlight the plight of species on the very brink of extinction. (A handful of species have even winked out from existence forever since Sartore’s traveling museum tour began). His artful animal portraits were created by having access to animals being safeguarded in zoos and captive breeding facilities.

Harris says that in some corners of the fine art ivory tower, there’s been longstanding biases against wildlife photography installations. Some have treated pictures as a lesser art form, compared to displays of paintings, sculpture and flashy experimental offerings, replete with special effects. Another prejudice is aimed at representational imagery (including wildlife imagery), which has been dismissed an illegitimate in the post-modern art world.

But the perception, he notes, is rapidly changing.

Far from passé, wildlife photography is, in some ways, avant-garde. With the proliferation of cameras in cell phones, photographic exhibitions actually have demonstrated broad appeal because the public innately understands the power of the medium. And, given the universal appeal of animals as icons, it is an art form that is accessible and one the masses can relate to.

“Engaging new, and this often means younger, audiences is something almost every museum I’m familiar with in the world is trying to do,” Harris says. “We intensively look for who is using animal imagery in thoughtful ways that speaks to old and new generations alike.”

The Mangelsen and Sartore exhibitions take nature photography to a new level, beyond that of Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter and Edward Weston who were the early pioneers of landscape photography. Photographers Mike “Nick” Nichols, James Balog, Paul Nicklen and others are making a profound difference too. They do what contemporary nature art ought to do: stir our senses and provoke discussion if not advancing awareness about environmental issues.

Harris adds that photographic exhibitions, in fact, have tended to produce both larger numbers of visitors and a higher volume of visitor comments. The National Museum of Wildlife Art has a renowned collection of priceless paintings and sculpture spanning centuries—works that would be considered treasures even in the Louvre. Several years ago, a small retrospective of Mangelsen’s work became one of the museum’s most popular in its history.

Jane Goodall, the legendary chimpanzee researcher who today is a global conservation ambassador is a close friend of Mangelsen and an ardent admirer of his work. “As I got to know Tom the man, I understood better the secret of the success of Tom, the photographer,” she said. “He portrays animals as individuals, complementing and bringing focus to the landscapes where they live. And he feels with his heart, as well as seeing with his eyes.”

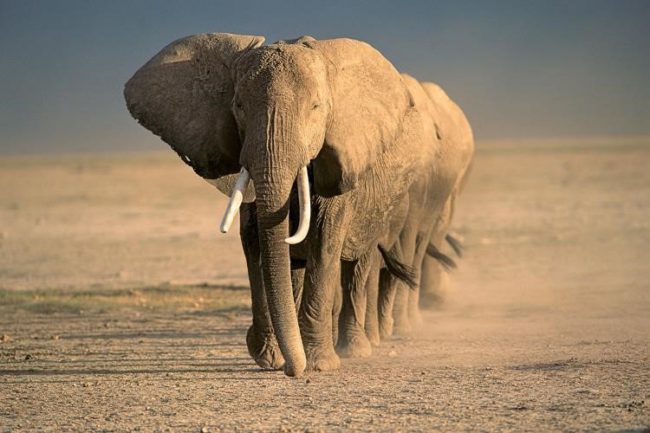

Sartore, nearly a generation younger than Mangelsen, told me he regards Mangelsen as a modern standard-bearer in validating wildlife photography as a vehicle for conservation and a way for collectors to declare their personal values on their walls. This spring in Los Angeles, an auction of 15 limited edition Mangelsen prints raised $165,000 to help combat elephant and rhino poaching in Africa.

“Tom Mangelsen has led the way with getting wildlife photography respected as fine art,” Sartore said. “If you go to a town where there’s a gallery with Tom’s pictures, it is a must-see.”

For his part, Mangelsen praises Sartore for daringly putting endangered wildlife at the forefront of public consciousness. It comes at an urgent time. Scientists say earth is entering the sixth major extinction episode; the only one caused by the proliferation of just one species—Homo sapiens.

As the name of Mangelsen’s exhibition implies, the photographs emanate from places he has spent his career exploring. Every single picture is “all wild”, notes David J. Wagner, the exhibition’s tour curator. “Some photographs picture pure wild places; other contextualize wildlife in their native habitats so that viewers understand subjects as an extension of setting.”

Were a young twentysomething to set out today trying to replicate what Mangelsen has done, it would be next to impossible because of the amount of time involved, the changes that have occurred in habitat, and the declining fortune of species, Wagner says.

“This is what adds to the mystique of Mangelsen’s legacy. Tom has borne witness to a wild planet rapidly being transformed right before our eyes,” Wagner adds. “As true reflections of nature’s beauty, his photographs inspire us to appreciate what’s still around us and to savor these other extraordinary beings that are part of creation. They force us to reflect on our own role as humans in being responsible stewards.”

Harris says the photography exhibitions at his museum, which are also traveling on to other prominent venues, stoke important societal discussions in a contemporary way.

“Both Joel and Tom have amassed their portfolios with a great deal of integrity and honesty about what they are doing. It doesn’t matter that Joel is taking photographs of thousands of animals in captivity because this is the only way, frankly, he can get shots of many critically imperiled species that are so rare in the wild and are in imminent danger of going extinct,” Harris says.

As for Mangelsen, his images are declarations of why wildness matters and how wild places are defined by the kinds of creatures inhabiting them, Harris points out. “Joel and Tom come at it from two different angles but the effect is the same: Their passion comes through. They open our minds and they cause us to care at a time when so many people in the world are disconnected from nature. You understand exactly where they are coming from in their perspective.”

A Life in the Wild also subtly hints at a controversy that’s been swirling among professional wildlife photographers for decades and it invites contemplation from anyone—which means all of us—who have cameras on our cell phones and take pictures of wildlife whenever possible, even at zoos.

As I’ve come to learn as an environmental journalist, most people who see nature photography online, published in books, magazines and appearing even in cinematography never question whether the photographs were actually created in the wild. If they did, they might be profoundly disappointed by the truth that a great many published images are shot at “game farms”—private facilities where captive wildlife rented out as models by owners of captive animal facilities.

Several years ago, Mangelsen and a group of leading nature photographers founded the International League of Conservation Photographers that has condemned the exploitation of wild animals by game farms, citing ethical, moral and animal welfare concerns. Another aspect of Mangelsen’s photographs is that they reveal only what he saw through the viewfinder and are not altered.

Digital manipulation of photography is not only rampant but it is an art form unto itself. Nowadays viewers don’t even know if the image in front of them came from a photographer actually spent time in the field observing his wild subjects or if the pictures are merely visual versions of music sampling.

“Nearly 50 years ago when I started my career, I wasn’t motivated by any notion that I was producing something special. I got up before dawn every day and stayed out past sunset observing nature because I loved being out there. The wild animals I’ve been blessed to see have been great teachers, often delivering humble lessons about our own place in the world,” Mangelsen says.

If his exhibition accomplishes anything, Mangelsen hopes it will encourage viewers, especially young people, to consciously make time over the course of their busy daily lives to just stop, dwell in the moment, take notice of other beings sharing spaces with them, let the natural world in as it reveals itself.

“Even if they can only be in a public park in the city with their cell phone cameras, use the lens to really see,” he says. “Don’t focus on your importance by taking a selfie. Put another sentient being in the frame and celebrate their presence. Our planet is a miracle in a dark cold universe. When it comes to nature, virtual reality is no replacement for the real thing.”

Thomas D. Mangelsen, who makes his home in Moose, Wyoming, has won numerous international awards for his fine art nature photography and has a legion of devoted collectors. His work has appeared in a number of prominent books and the pages of National Geographic magazine among others. Click here to learn more about Mangelsen’s A Life in the Wild exhibition.

Joel Sartore, like Mangelsen, a Nebraskan, has long been affiliated with National Geographic and is also counted the foremost wildlife photographers in the world.

Writer Todd Wilkinson has been an award-winning environmental journalist for 30 years and is a national authority on wildlife art. The author of several books, he also is a correspondent to National Geographic publications and the founder of a new online public interest journalism magazine, Mountain Journal debuting in August 2017 that focuses on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. He collaborated with Mangelsen on the recent book Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone that won a 2016 High Plains Book Award.

Thomas D. Mangelsen — A Life in the Wild, is a traveling museum exhibition produced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C. Museums, art, nature and science centers, libraries, universities, botanical gardens and zoos interested in hosting the exhibition are encouraged to contact:

David J. Wagner, Ph.D. | Curator/Tour Director

www.davidjwagnerllc.com | davidjwagnerllc@yahoo.com | (414) 221-6878

The above post is through the MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artwork processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems and contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the space.

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/creative-expressions/life-in-the-wild/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.