Geoff Holland – If you were an omniscient observer watching over life on Earth at this moment, what would you see?

Jelani Cobb – I would see a tragic redundancy, a tragic repetition of previous patterns. Despite all that we’ve learned, or have the ability to learn. We have a failure to apply what we’ve learned. A frustrating inability to prioritize long-term objectives over short-term profits. That’s why we see things like climate change and a return to threats of using nuclear armaments. We would also see millions, hundreds of millions, billions of fundamentally good people, people who would do the right thing, people who would help each other, if they had the opportunity, but haven’t been empowered to change the world in ways that would be beneficial.

GH – The cultural clouds looming these days are uncertain at best. When you look at the big picture of our Earth, what troubles you the most?

JC – Climate change…climate change and the frustrating, halfhearted efforts to address it. There are still too many people trying to protect fossil fuels in the context of climate change. Another big problem is population growth. We’re not devoting the attention required to provide a decent living standard for every child born on this planet. Basic access to food and clean water. Every person is owed that much.

GH – As a seasoned journalist operating at the human cultural leading edge, what are the factors currently at play that could swing the human culture in a life-affirming direction?

JC – After World War Two, the planet grappled with the implications of war in a way that we had never done before. And, you know, we created the United Nations and eventually created international regulations on nuclear arms and other challenges so that they could be managed properly for all the right reasons. Sometimes movements will arise – religious movements, social movements – that focus the attention of a great number of people on a single problem. That’s a way to create positive change. And then sometimes, we have the advent of a technological change; a development that makes it possible for you know, penicillin for instance, which is medical, not technological, but a huge good can come out of nowhere, and no one anticipated it.

GH – These days, there is so much cultural dysfunction on a global scale. How important is it for journalism to rise to the needs of our time?

JC – It’s crucially important for journalism to rise to the needs of the moment when we are navigating in the dark. We have seen an unprecedented level of misinformation and disinformation promulgated on a global scale. Social media has made it possible for us to communicate with people across the globe and interact and be aware of current events in ways that we couldn’t imagine before, but that’s also made it possible to mislead people on a scale that would have been difficult to achieve previously. We need journalism to step into the void there. And we need to have really accurate, really serious, really efficient work that the public can place its faith in. Worthy journalism is one of our best options for navigating the situation we’re in right now.

GH – The public and social media are awash in content intended to mislead and misinform. What is legitimate journalism’s remedy for that?

JC – I don’t think that the remedy for that necessarily comes from journalism. I think that journalism has the job, the responsibility, of putting out as accurate, as fair, as complete an examination of every single issue that we cover, and as much as is humanly possible. But that doesn’t completely answer the problem of misinformation and disinformation. Some of that will require regulation, so there’s less production of misinformation and disinformation. As it stands, I think there’s no incentive for tech platforms to do that. We should change that. There should be more incentivization that encourages clearing out the misdirection and cleaning up the media platforms.

GH – The Partnership Way is a cultural course with women, men, and non-binary humans standing together, sharing equal rights and responsibilities. Does ‘partnership’ and cooperation offer humanity the best chance of getting past the worst in us?

JC – Yes. I think that’s so. Throughout human history, there’s been a terrible capacity for destruction, isolation, and individualism. But, we also have a great capacity for help and cooperation, and benevolence. I think that we really can only hope that we can marshal enough of those skills and traits to navigate the increasingly treacherous environments in which we find ourselves.

GH – Young people are tuned in to every kind of public and social media. What are the best media pathways for journalism to inform all humans, and particularly young people in all places, about the powerful cultural forces at work in our world?

JC – I don’t know the answer to that. I think that’s a question that journalism is grappling with. We don’t know what the delivery mode of information will be. Some people think it’s a tech platform, an app, or a website, but we really don’t know, and it would be wrong to kind of surmise that this is what we think will be. That’s the question that confronts journalism. That’s the question we’re trying to figure out. The playing field is changing constantly, so it’s hard to get a handle on that.

GH – What are the cultural trends you see that make you optimistic about our human future?

JC – I think we have a broad sense of the landscape of peril that we confront. We have the advantage of having reached a point where we know what the problems are, or what the pressing issues are. We’re no longer really trying to convince people that climate change is real. There’s much more that the public understands. So, that gives me hope. I also think that throughout our global history, there’s always been, at least some community of people who aspired toward a greater and more peaceful existence. And we see those movements around the world. I take inspiration from them, whether they are the women in Iran, the young activists fighting against climate change, or the journalists who are risking their lives to expose the atrocities in Ukraine.

GH – Given so much planetary-scale uncertainty, and the pace of change accelerating, will we humans transcend and find our way to a worthy future?

JC – I mean, it’s possible. The thing I think about is that today when I give talks, I have the optimism of a boxer in the late rounds. And what that means is, if you’re still on your feet, if you haven’t been knocked out yet, then you have a chance to win. And so, we haven’t been knocked out yet. We do have a chance at creating a better future.

GH – What does the best kind of human future look like to you?

JC – I’ve thought about this a lot. Let’s start with free access. By free I mean open, affordable access to medical care, globally recognized health care should be a human right. Let’s have every child born into a community have free access to clean water. Let’s have a world in which someone’s options and possibilities for an education and a future are not contingent on their gender. Let’s shape a world in which women are completely and totally empowered to live as full a life as any man; a world in which we’ve tackled and addressed the needless blight of poverty, which is entirely a product of greed. I think those things, along with eliminating the worst of our tribal selves that result in things like racism, anti-semitism, islamophobia, and misogyny. Once we’ve tackled climate change, that’s kind of a starting framework for what a better world would look like to me.

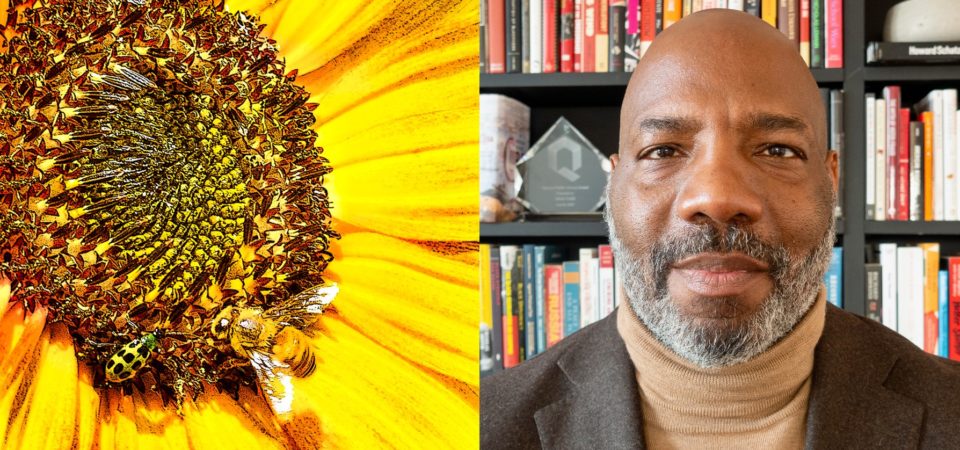

Jelani Cobb is the Dean of the Columbia University School of Journalism, where he is also Henry Luce Professor of Journalism.

He has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 2015. He received a Peabody Award for his 2020 PBS Frontline film Whose Vote Counts? and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Commentary in 2018. He has also been a political analyst for MSNBC since 2019.

He is the author of The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress and To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic. He is the editor or co-editor of several volumes including The Matter of Black Lives, a collection of The New Yorker’s writings on race, and The Essential Kerner Commission Report. He is a producer or co-producer on a number of documentaries including Lincoln’s Dilemma, Obama: A More Perfect Union, and Policing the Police.

Dr. Cobb was educated at Jamaica High School in Queens, NY; Howard University, where he earned a BA in English; and Rutgers University, where he completed his MA and doctorate in American History in 2003. He is also a recipient of fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the Fulbright Foundation, and the Shorenstein Center at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.