Geoffrey Holland – You are an art historian focused on nature and wildlife art. What drew you to those genera as the focus of your life’s work?

David J. Wagner, Ph.D.[1]– My work as a writer is dwarfed by my work as an arts administrator, but important because research and writing have grounded me in historical knowledge and philosophical thought. These were essential for writing my book, American Wildlife Art, and the occasional exhibition I have had the good fortune to curate. My first interest in nature and wildlife art can be traced back to my childhood. I was reared in a family of hunters and fishermen. Like them, I was a hunter and a fisherman, though I grew away from hunting as an adult. As a young boy, I enjoyed the romance of outdoor sportsman magazines, their stories, and the illustrations.

My junior high school biology teacher steered me to join The Izaak Walton League and attend Trees for Tomorrow Camp in Wisconsin’s north woods. In high school, I worked at The Wisconsin Youth Conservation Camp (akin to FDR’s CCC) for two summers, and then went off to attend the University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point, which is well known for its College of Natural Resources. I didn’t excel in the sciences, so I fell back to my natural ability and enrolled in The School of Fine Arts. While working a summer job in northern Wisconsin following my freshman year in college, I spotted an ad for an art show at a gallery in Minocqua. It featured work by Owen Gromme. Some would say he was the dean of wildlife art in this state. It was his work that introduced me to wildlife art. In graduate school, I majored in arts administration and focused on museum management. Upon graduation, I was offered a job at the ridiculous age of 24, to be the director of a new art museum in Wausau, Wisconsin. The founders of the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum who hired me had an interest in a subset of wildlife art—bird art. So much so that it was the chief focus of the museum, and that’s where my career really began. In my 20s, I was able to work with leading A-list wildlife artists of the day and get to know them personally, and exhibit their work. The list includes Owen Gromme, Roger Tory Peterson, George Miksch Sutton, Guy Coheleach, Don Eckelberry, Arthur Singer, J. Fenwick Lansdowne, Peter Scott, Keith Shackleton, Kent Ullberg, and an up-and-coming artist named Robert Bateman.

Early on, I started organizing tours of the museum’s exhibits. One of the first venues I toured for the museum’s annual bird art exhibit was The National Collection of Fine Arts (since renamed the Smithsonian American Art Museum). Other venues followed throughout the lower 48 states, Alaska and Hawaii, and overseas including The Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh;The British Museum (Natural History), now The Natural History Museum, London; and The Beijing Museum in China.

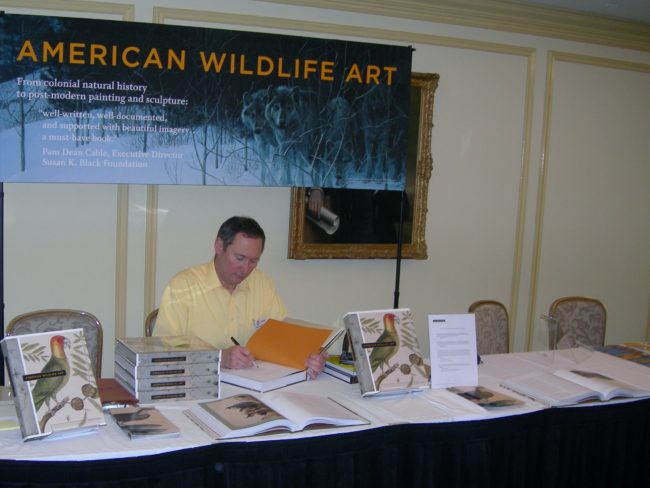

During these formative years, I realized that I didn’t know much about the subject that I was so involved in. So, I decided to go back to graduate school to learn all I could. While I was a young museum director, I enrolled in the American Studies Ph.D. program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, which I felt was the best academic fit for my subject. The Board of Directors of The Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum supported me by generously giving me release time and paying my tuition. I felt a real-life connectedness between my pursuit of a Ph.D. and my professional career. So it was natural for me to write my dissertation on the history of wildlife art, wildlife art prints to be exact. Over the years, I got to know the founders of The National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Bill and Joffa Kerr. Thanks to them, the William G. Kerr and the Robert S. and Grayce B. Kerr Foundation funded a sabbatical for the research and writing necessary to transform my dissertation into my book, American Wildlife Art. Later, James E. Parkman, founder, and Chairman of the Susan K. Black Foundation, generously funded the production of the book itself.

Of course, I have also conducted research and written as a curator of museum exhibitions produced by my company over the years, including America’s Parks, American Birds, American Wildlife Art, Andrew Denman: The Modern Wild, Animal Groups, Animals in Art, Art and the Animal (from the Society of Animal Artists), Art of the Dive / Portraits of the Deep, Art of the Rainforest, Biodiversity in the Art of Carel Pieter Brest van Kempen, Blossom ~ Art of Flowers, Brian Jarvi’s African Menagerie, Cory Trépanier’s Into The Arctic, Crocodilian Scratchboards by John Agnew, Endangered Species, Flora and Fauna in Peril, Environmental Impact, Feline Fine: Art of Cats, Cultivating the Dutch Tradition in the 21st Century – Jane Jones’ Hyperrealist Floral Paintings, John James Audubon, Kent Ullberg: A Retrospective, LeRoy Neiman, On Safari, Mick Meilahn’s Primordial Shift, Paws and Reflect: Art of Canines, Robert Bateman – A Retrospective, Sandy Scott: A Retrospective, Sayaka Ganz: Reclaimed Creations, The National Geographic Society Outdoor Sculpture Garden, The Horse In Fine Art (annual exhibition of the American Academy of Equine Art), The Sea of Cortez, The Art of Robert Bateman, and Thomas D. Mangelsen: A Life in the Wild. These exhibits and others have toured and continue to tour to venues throughout the US and in Canada under the auspices of David J. Wagner, L.L.C.

That’s essentially the story of how I became focused as a historian on wildlife and nature art.

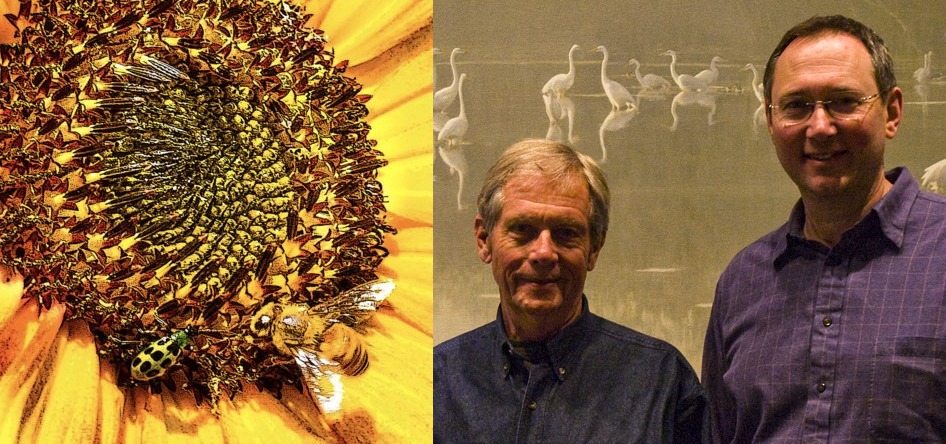

GH – The Bee Project is a current exhibit curated by you. Can you talk about what is involved in steering an idea like that to a worthy public presentation?

DW – The Bee Project was developed by artist Elena Smyrniotis while she was a Grant Wood Art Colony Fellow at the University of Iowa (UI), in collaboration with the UI Office of Sustainability and the Environment. Elena is a Russian immigrant, who like Rudolf Nureyev comes from Ufa (NB: the capital of the Republic of Bashkiria).

For scientific content, Elena partnered with UI Professor Emeritus Steve Hendrix, who earned his Ph.D. at the University of California – Berkeley and subsequently focused on plant-animal interactions, including reactions of plants to herbivores, and pollination ecology of prairie plants. Elena was recommended to me by Japanese artist Sayaka Ganz, whose Reclaimed Creations exhibition I tour, and who, like Elena, resides in Fort Wayne, Indiana. After acquainting myself with Elena’s oeuvre, I thought her bee project had the best chance of succeeding in the marketplace of traveling museum exhibitions because of its timely mission and potential to engage audiences. The mission of The Bee Project is first to make a positive contribution toward a sustainable future for pollinators; second, to encourage the protection of fragile ecosystems; and third, to engage broad and diverse audiences, particularly children. When I was introduced to Elena, she had staged The Bee Project locally in Iowa.

My concept was to export it nationally. I therefore guided her in the creation of a prospectus that my company distributed to a massive mailing list of museums and other art, cultural, and scientific institutions such as nature and art centers, botanical gardens, and zoos. I am pleased to say that institutions in Connecticut, Kansas, New Jersey, and Tennessee signed up to host the project. More are pending, which gives me a sense of satisfaction. The Bee Project is an outdoor, site-specific installation of modular structures resembling beehives populated by bees creatively and often lovingly made by participants from recycled materials, mostly plastics and metals. The project’s beehive structures are fabricated from carbon steel mesh in the shape of hexagons and painted yellow to resemble a honeycomb. They vary in height from 3 to 6 feet and can be placed in any number of configurations, considering the contour of the landscape, buildings, trees, and paths of human traffic.

GH – Another exhibit series you have curated is a celebration of the remarkable work of wildlife photographer, Thomas Mangelsen. Can you talk about the process and commitment that is reflected in Mangelsen’s work?

DW – In 2016, Todd Wilkinson (author of Science Under Siege: The Politicians’ War on Nature and Truth, Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet, and Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek: An Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone, among others) recommended me to the management team of Thomas D. Mangelsen, to produce and manage a traveling exhibition of his photographs. Mangelsen himself was already familiar with my work through traveling museum exhibitions I previously produced for two mutual friends, Canadian painter Robert Bateman, and Swedish-American sculptor Kent Ullberg.

Mangelsen’s exhibit was quick to take off. To date, two simultaneous national tours of his A Life In The Wild, each running for over 4 years, have been displayed at about two dozen venues, with more to come.

But I did not “curate” the exhibit per se. Its forty photographs were personally selected by Mangelsen as legacy photographs, meant to showcase his best work so far. My role as a curator has been to ensure that the exhibition and its management comply with museum best-practice standards. Thomas Mangelsen has traveled to the most far-flung, wild places for over 40 years in pursuit of wildlife and their habitat, and produced a body of work second to none. In today’s digital age, A Life In The Wild stands as a testament to his achievements and the rewards that can come to those, like him, who get close to nature.

Photographs in the exhibit feature American bison, Arctic fox, bald eagle, Bengal tiger, black bear, bobcat, bohemian and cedar waxwings, brown bear, coyote, elephant, flowers including poppies and lupine, giraffe, great gray owl, grizzly bear, ground squirrel, kestrel, king penguin, landscapes such as the 10-foot wide Alaska’s Denali range and the Great Smoky Mountains, leopard, lilac breasted roller, moose, mountain lion, polar bear, Sandhill crane, silverback mountain gorilla, groves of trees including redwood and aspen, western tanager, and zebra.

Photographs that the public will generally be familiar with are those of polar bears, including Polar Dance (1989), and certainly Catch of the Day (1988), which captures the exact moment that a spawning salmon, trying to leap over a waterfall along Alaska’s Brooks River, soars right into the waiting jaws of a massive brown bear. About Catch of the Day, Todd Wilkinson wrote that it is not only one of the most widely circulated wildlife photographs in history but also a monumental achievement in photography because it occurred before the advent of digital cameras and involves no digital manipulation. And I might add, it has been widely mimicked. One of the most prolific nature photographers of our time, Mangelsen has been described as a spiritual descendant of pioneering nature photographers such as Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, and Edward Weston. Bill Allen, retired Editor-in-Chief of National Geographic, considered Mangelsen to be one of the most important nature photographers of his generation. In addition, Thomas Mangelsen is as much a conservationist as he is an artist. He was named the 2011 Conservation Photographer of the Year by Nature’s Best Photography, placing his work in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. He was named one of the 40 Most Influential Nature Photographers by Outdoor Photography, and one of the 100 Most Important People in Photography by American Photo magazine. The North American Nature Photography Association named him Outstanding Nature Photographer of the Year, and the British Broadcasting Corporation gave him its coveted, prestigious award, Wildlife Photographer of the Year.

GH – You have a long relationship with Robert Bateman, who many regard as the greatest wildlife artist of all time. Can you talk about what makes Bateman’s artwork so compelling?

DW – Robert Bateman was born in 1930 in Toronto, the son of an electrical engineer, and homemaker. The mother introduced her son to wildlife art when he was eight by enrolling him in the Junior Field Naturalists Club at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum. There, he learned to make field sketches under the instruction of watercolorist Terence Shortt. As a high-school student, Bateman took painting lessons from Gordon Payne and spent summers working in Algonquin, the largest and oldest Provincial Park in Ontario. This experience enabled him to observe animals in the wild and to sketch and paint landscapes in the park just like his beloved members of Canada’s Group of Seven began about two and one-half decades earlier. After high school, while majoring in geography at the University of Toronto, Bateman took extracurricular evening courses in drawing from Carl Schaefer who taught the method of Kimon Nicolaïdes, which emphasized draftsmanship, especially for figure drawing (The Natural Way to Draw: A Working Plan for Art Study, Houghton Mifflin in 1941).

It not only grounded Bateman in traditional fundamentals of art but many of his generation: “He taught us to work with boldness, to have power and rhythm in the main structure of the painting, and brushwork that showed vitality.”[2]

After graduating from college, Bateman set aside the lessons he had learned from Terry Shortt and Carl Schaefer, and the influence of Canada’s Group of Seven, to struggle with other idioms of artistic expression. This resulted in a body of work over the next ten years that Bateman himself characterized as eclectic and trendy: “I became interested in the work of Picasso and Braque and I found myself using these techniques of perspective and distortion to depict my own world. During this whole period, though I painted in many different styles, I generally chose subjects in nature, as opposed, say, to wine bottles or the interiors of rooms . . . My admiration for the way Oriental painters could capture things in a few strokes led to my excitement with the work of Borduas and some of the abstract expressionist painters of the New York School in the 1950s—people like Franz Kline, who is one of my great heroes, and Motherwell, Rothko, and Clyfford Still. . . . In a sense, I didn’t know who the real me was . . .”

An end to his search for an artistic identity came in 1963, when, after attending a retrospective exhibition of the work of Andrew Wyeth (born 1917) at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, New York, Bateman rediscovered the possibilities of representational painting, so much maligned by the art world in the 1940s to 1960s.

Andrew Wyeth possessed a style that had evolved not from the genre of American wildlife art but from literary illustration—a style taught to him by his father, N. C. Wyeth, a renowned book and magazine illustrator who had apprenticed in Wilmington, Delaware, with Howard Pyle, one of America’s earliest and most influential illustrators. By adapting Wyeth’s style and technique for the portrayal of nature, Bateman would go on to produce a body of work that I would characterize as “classic Robert Bateman”. This endeared him to admirers and collectors in Canada, The U.S., and The U.K. from the mid-’70s throughout the ’80s and beyond. After Bateman found his artistic identity, he advanced the story of American wildlife art in yet another way.

By the end of the 1980s, Bateman had also aligned his art with the Environmental Movement. An early example of this integration is Mossy Branches—Spotted Owl, painted in 1989 and published as a print for a wider market by Mill Pond Press in 1990. The spotted owl had become a potent symbol in the Pacific Northwest because a traditional cornerstone of economic life in the region—logging—was not only affected by but actually impinged upon the bird’s status under the Endangered Species Act.

As portrayed by Bateman in Mossy Branches, the owl is on one hand a portrait of a seemingly benign bird in its native habitat; on the other hand, it is a powerful symbol of a highly charged issue for a region in which logging threatens old forests and images of spotted owls are themselves threatening to loggers. To convey the interdependence of the owl and its habitat, Bateman backlit the bird with raking sunlight and used this compositional device to set off rich mosses that, like the owl itself, rely on the ecosystem of old-growth forests for sustenance. A still background of dense forest darkened and flattened through a scrim of gray fog, provides contrast. Although Bateman hid the owl behind branches heavy with mosses, he also placed it front and just left of center for compositional impact. To heighten this effect, Bateman cropped the composition tightly, giving it the appearance of a snapshot and the shy owl an enigmatic expression that begs interpretation.

Taking advantage of the opportunity that his commercial success brought him, Bateman pushed the limits of wildlife art even further by creating controversial paintings such as Carmanah Contrasts. It grew out of a collective effort by artists who gathered on Vancouver Island in British Columbia in 1989 to document the clear-cutting of the Carmanah Forest, an old-growth area. They agreed to collectively publish their work and create awareness and resistance. And it contrasted old-growth and clear-cut forest imagery in a style that foreshadowed a new stylistic movement in wildlife art known as postmodernism. The first in what Bateman called his “environmental series”, Carmanah Contrasts consisted of contrasting images in contrasting styles layered in meaning. At one level, Carmanah Contrasts portrays imagery representationally; at another, it overlays traditional representational style with an abstract style known as color-field painting, which had its roots in the 1960s in the part of the abstract art movement known as minimalism. As its name suggests, color-field painting consists of large fields or blocks of color. As such, it was conceived to focus the attention of viewers on art elements and principles purely for their own sake. Many more avant-garde paintings by the artist followed. For my Ph.D. dissertation, I conducted a survey of wildlife artists to track the influence of one artist upon another. Robert Bateman was said to be more influential than any other at the time.

Robert Bateman became North America’s most influential living wildlife artist because his aesthetic went beyond the didacticism of natural history image making, impression, and illustration, and also because it was purposefully integrated with the ecological ideology of environmentalism.

[1] The first half of my career was as a museum director. The second half has been as President of David J. Wagner, L.L.C., a limited liability corporation established in the state of Wisconsin for the principal purpose of producing and managing traveling exhibitions for display at museums and related art, cultural and scientific institutions in North America and abroad. I have also occasionally served as adjunct faculty at several colleges and universities.

[2] Ramsay Derry, The Art of Robert Bateman (New York: The Viking Press, 1981) p. 21

Continue reading the full dialogue by downloading the PDF from the link at the top of the page.

David J. Wagner is the founder of David J. Wagner, L.L.C., a limited liability corporation established in the state of Wisconsin for the principal purpose of producing and managing traveling exhibitions for display at museums and related art, cultural and scientific institutions in North America and abroad. He earned his Ph.D. in American Studies at The University of Minnesota and previously served as a museum and art center director for 20 years. His book, American Wildlife Art, grew out of his Ph.D. dissertation thanks to a Post-doctoral Fellowship funded by The Robert S. and Grayce B. Kerr Foundation, and publication funding from James E. Parkman, Chairman, Board of Directors, Susan K. Black Foundation, with additional support provided by The Newport Wilderness Society, Inc. from a grant from the Peninsula Art Association and the Wisconsin Arts Board. In addition to having served as President of his own company which he began in 1998, David J. Wagner has conducted lectures and book signings, served as consultant and guest curator, and adjunct faculty at several colleges and universities. Further information is available at: davidjwagnerllc.com

Find out more:

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.