An externality is a positive or negative consequence of an activity experienced by unrelated parties. In many situations, society applies rules to reduce negative externalities or incentivize positive externalities. Taxes or regulations penalize pollution, subsidies pay for vaccinations. These ideas and policies are generally accepted until we come to childbearing decisions. Even people highly concerned about overpopulation tend to believe:

- Childbearing is a fundamental human right

- Society has no business telling couples to have fewer or more children

- China’s “One Child” policy and India’s 1970s family planning programs were immoral

But we are social animals. Positive externalities from other people are keys to human survival. Other people’s children have enormous impacts on my children. Division of labor means your child grows food for my child, a doctor saves my child’s life. Other people’s children provide friends, lovers, colleagues, inventions and so on.

Under other circumstances, where there are too many people and not enough resources, your child might negatively impact my child. The planet is heating up because of other peoples’ consumption of fossil fuels and clearing rainforests. Too many people drive up food prices until children starve in poor countries. Your child could bully or outcompete my child. Your child might get the admission to college or a job that my child applied for. At crowded tourist attractions, my child stands in line behind your child. Your kids are why I’m stuck in traffic. Housing costs more because your child pushes up demand. At humanity’s worst, other people’s children torture or kill others with murders, wars or genocides.

Garrett Hardin, in his 1968 article “Tragedy of the Commons,” pointed out that individually rational decisions to have another child could lead to collectively unacceptable outcomes—poverty, pollution, overpopulation, wars, species extinctions; all negative impacts on each other and the planet’s “global commons” that parents may not consider.

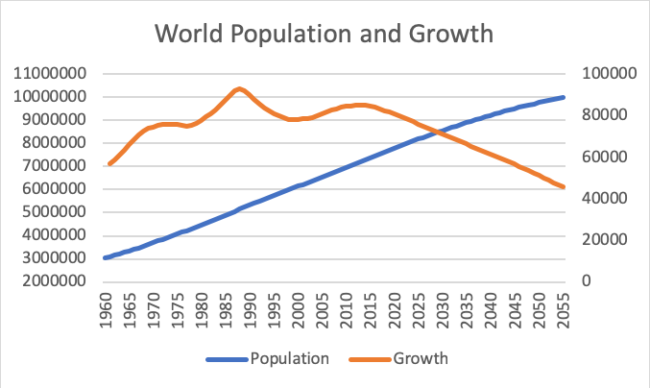

The taboo about even talking about using public policy to fix externalities of childbearing and resulting overpopulation doesn’t make economic or ecological sense. At present, individual decisions are increasing population by a billion every 12 years. Climate, soil, fossil fuels and species diversity are running out. Global population will grow from 3 billion in 1960 to 10 billion by 2055 (UN projection). Scientists calculate long run sustainable population at 1-2 billion.

Source: UN Population Prospects 2017 Revision

Note the optimism: Decline projected despite continued growth at 80 million/year so far. Future changes are conditional on future policies and fertility outcomes. Fertility decline has slowed to near zero.

Nobody decides how many children to have in a vacuum. Every society regulates reproduction in powerful ways. People learn fertility norms (ideal family size) from their culture, parents and peers. There are laws and social norms concerning marriage, child support, inheritance and many other institutions that influence childbearing decisions. Pro-natalist and anti-natalist economic incentives include tax deductions for children, public education of children, old age pensions (so we don’t need kids to support us) and so on. Almost nowhere do women come close to bearing the maximum biologically possible number of children.

A two-child policy is common sense—the planet isn’t getting bigger, why should population keep growing? Two parents, two children, stable, sustainable. After half a century of further increase due to “demographic momentum,” as children grow up, have children and age, population could then begin a slow adjustment down to long run sustainable population. Wherever women have been liberated and societies modernized, fertility rates that reached replacement levels (about 2.1 children/woman) have continued downwards, often to 1.2 to 2.0.

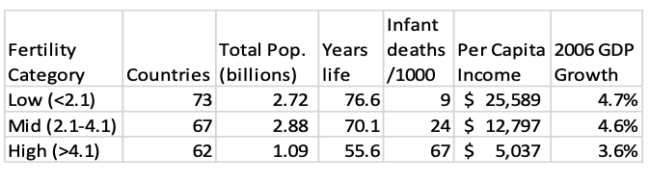

If you say, “unacceptably coercive,” remember that the smartest, most educated and prosperous women in the world freely choose, on average, less than two children. Why not re-imagine small family size as liberating and empowering for women and a path to sustainable prosperity for all? Data shows much better income and health outcomes in low fertility countries. The table shows five times higher incomes and 58 fewer infant deaths per 1000 births in low fertility countries compared to high fertility countries.

Source: U.N & World Bank 2006-2008 figures (table from Kummerow 2009)

Ken Boulding, author of an essay on “spaceship earth,” proposed endowing everyone with equal limited child bearing rights and making them tradeable. So, people who really wanted more children could buy childbearing rights from those who would accept fewer, without increasing the total population burden. (A cap and trade system). Much less radical programs emphasizing improving status of women, education and provision of family planning health care services have been enough to reduce birth rates in dozens of countries. Optimum population and how to get there humanely should be one of the main political debates and marketing campaigns of the 21st century. If marketers can sell us everything else, they can also sell the benefits of low fertility rates. Public relations campaigns like “two is enough” have been effective in some countries.

The first step towards rational, life enhancing policies would be wider awareness of the consequences of overpopulation. At some stage, we will learn to think like people in a lifeboat. In a lifeboat, space is scarce. If too many climb aboard, the boat will sink. Climate change is literally sinking our lifeboat as sea levels rise. A “sixth extinction event” is wiping out species, destabilizing ecosystems we rely on. David Attenborough has begged us all to “talk about population.” Organizations and individuals concerned about the many problems caused by overpopulation—from traffic congestion to climate change—should gather the courage to address this fundamental issue. Mass media, in the U.S.A. and elsewhere, could do a better job of covering the ongoing developing story of too many people sinking lifeboat earth.

Having children endures as a fundamental human right, so morally defensible policies on reproduction must apply equally to everyone. China recognized the principle of equal rights for all by charging people heavy fines for extra children. A couple who had extra children were being selfish, using more than their fair share of overpopulated China’s limited resources.

Before science, human populations were automatically regulated mainly by ‘density dependent mortality.’ A woman could have a dozen births or more and several miscarriages. She might die young from complications of childbirth. Half the babies born died of infectious diseases or malnutrition in the first year of life. Diseases, famine, and war regulated populations.

Human population grew very slowly for 400,000 years then growth accelerated. Current world population growth (80 million per year) equals about 8 times total world population (10 million) in 10,000 BCE. Now that most babies born live to adulthood, we have found more humane paths to population regulation through family planning—choosing to regulate fertility rates so women have fewer births and we all live longer.

But we haven’t yet implemented reliable institutions to promote equality of childbearing opportunities and regulation of overall world population to levels the planet can support. Possible futures look grim to scientists who study ecosystem services and limits to growth. History shows dozens of cases of population overshoot and collapse in past civilizations. Ancient Rome’s population peaked at over a million then fell to less than 50,000. The march of folly continues with short run rewards motivating individual childbearing decisions despite long run costs to us all.

Humane institutions to adjust fertility preferences include education, tax incentives or subsidies, family size norms, child protection services, laws and easy access to affordable birth control, abortion and sterilization. Although some of these may sound onerous, a less crowded world leaves us more free, less stressed, richer and more peaceful. Social justice and good government also become easier in a world of abundance. Policies recognizing the external costs of our children on others would help protect everyone’s fundamental rights to live well on a healthy and recovering green planet shared with an interdependent community of life.

Negative externalities, problems caused by other people’s children, have not been solved or even widely recognized. Until individuals experience the full costs their children impose on the rest of us and policy deals with the collective “tragedy of the commons” due to overpopulation resulting from individual decisions that don’t take account of the full costs of overpopulation, I doubt the world will find a path to population stability and lasting prosperity. Country average fertility rates currently range from about 1.1 to 7. Divergent fertility drives migration from poor high fertility countries to rich low fertility countries and perpetuates population growth, poverty and environmental destruction. None of us can escape these global problems. How will voluntary individual choices reduce births by 80 million per year?

Decisions to have children should weigh negative effects on others and on ecosystems. Individually rational utility maximizing decisions can accumulate to irrational negative outcomes for all. Other people’s children do determine our children’s fate on a crowded planet. Some rights, even the most fundamental human rights, must be limited to protect those same rights.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.