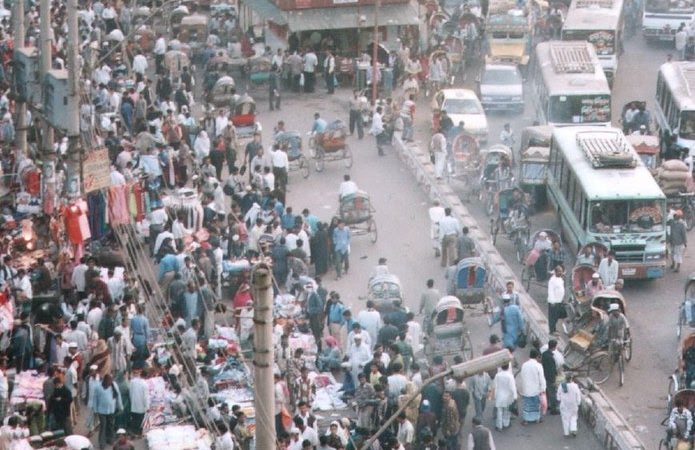

The news that primary students in Uttar Pradesh were given salt with Roti (bread) as a midday meal sent shock waves across India last year. Uttar Pradesh has a population of 200 million people, it has more people than Brazil and Nigeria. More than a quarter of the state’s residents (60 million people) live below the poverty level. When it comes to food security, population has become a liability for India — with only 2.4 percent of the world’s total land area India has to support 14 percent of the world’s total population. India is set to surpass China as the world’s most populous nation by as early as 2024. In a country where 50 million people live on less than $2 a day, and 194.4 million people are undernourished the growing population will only make food security situation worse. One of the underlying causes of malnutrition is poverty and poverty is far from being eradicated. The government has large food security and anti-poverty programmes but there are critical gaps in terms of inclusion and exclusion errors.

India may be thriving economically, but it is still dogged by poverty and hunger. In the Global Hunger Index, India ranks 102nd out of the 117 qualifying countries. Forty-six million children in India remain stunted and 25.5 million more are defined as “wasted” — meaning they do not weigh enough for their height. India’s child wasting rate is extremely high at 20.8%—the highest wasting rate of any country. It is usually the result of acute significant food shortage and/or disease. Among countries in South Asia, India fares the worst (54%) on the prevalence of children under five who are either stunted, wasted or overweight. In India, poor supply chain management practices have led to as much wastage as the United Kingdom consumes. Research suggests that $1 spent on nutritional interventions in India could generate $34.1 to $38.6 in public economic returns, three times more than the global average.

Too often, new mothers are adolescents. The malnutrition of Indian children often starts in the womb. A staggering 75% of them are anemic and most put on less weight during pregnancy than they should – 5 kilograms on average compared to the worldwide average of close to 10kgs. Malnourished adolescent girls cannot deliver healthy babies, thereby perpetuating the intergenerational cycle of under-nutrition. Malnutrition caused 69 percent of deaths of children below the age of five in India.

A growing population will exacerbate climate change effects and further stress food insecurity. Climate change affects malnutrition in a myriad of ways. Climate change reduces agricultural yields and the nutritional value of staple crops, and it increases the prevalence and spread of diseases. Projections show that climate change will increase stunting by 30 percent to 50 percent by 2050. These and other effects are closely linked with malnutrition in poor communities. Currently, 49% of India’s land is under drought. During a drought, millions more are at risk for falling into poverty and food insecurity. Multiple years with droughts creates chronic poverty to hundreds of millions. High consumption and a growing population are inextricably linked to global warming and climate change and India stands to be one of the nations most significantly affected by climate change. One of the biggest issues confronting Indian agriculture is low productivity. Indian agriculture, and thereby India’s food production, is highly vulnerable to monsoon variability. After all, about 65 percent of India’s cropped area is rain-fed. Because large parts of the country already suffer from water scarcity and depend on groundwater for irrigation, further droughts and changing monsoon seasons impact the systems millions of people depend on for their basic needs.

A study by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) summarizes this serious situation in India: population explosion has exceeded agricultural growth rates in the post independence period and unequal distribution systems make it difficult to ensure everyone has access to food.

India needs to take immediate steps to address this problem, access to reproductive health services has to be made available to men and women. Among developing countries, India has the highest number of women — 31 million with an “unmet need” for contraception, according to RAND survey research. The ability to decide when or whether to have children is not only a basic human right; it is also the key to economic empowerment, especially for poor women. The longer a woman waits to have children, the longer she can participate in the labor force, thereby helping to improve the economic health and prosperity of poor communities. Investment in human capital produces immediate gains for developing economies. If these women are provided access to contraception, millions would come out of poverty and the rate of educational attainment would also improve. For every dollar that is invested in reproductive health services around the world, $2.20 is saved in pregnancy-related health-care costs.

Organisations like Family Planning Association of India (FPA India) are working to improve the health services among women. FPA is a social impact organisation delivering essential health services focusing on sexual and reproductive health in 18 states of India. FPA India creates awareness among marginalised and vulnerable women on sexual and reproductive health. FPA India was instrumental in making India the first country in the world to have a family planning programme after independence. FAP India has provided health services to 3.5 million people and operates 117 clinics with 106 doctors and 62 health services.

In Jharkhand which is the second most resource-rich state in India, 39 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. The Jharkhand government worked with Georgetown University’s Institute for Reproductive Health to offer Cyclebeads as a free contraceptive option on all of the state’s districts. The program led to an increase of contraceptives in many villages all over the state. Extending this program all over India will have a positive impact on the reproductive health of people.

India’s biggest challenge still remains ensuring food and nutritional security to its masses. India experiences food shortage which results in chronic and widespread hunger amongst a significant number of people. Big initiatives have to be taken to improve food security as India faces supply constraints, water scarcity, small landholdings, low per capita GDP and inadequate irrigation with burgeoning population. Workers in India need to be educated in farm efficiency and technological advancements. It also makes it easier to train and acquire new skills and technologies required for productivity growth.

Urgent steps need to be taken by the government to tackle climate change, alarming rates of groundwater depletions and increasing environmental and social problems pose acute threats to people all over India. NITI Aayog, a research institute affiliated with the Indian Government, claims that ‘India is suffering from the worst water crisis in its history’.

The contraceptive usage rate, which was 56% in 2015-16, has remained little changed from the previous survey done in 2005-06. The government needs to improve access to all contraceptive methods as other progressive Asian countries did decades ago. Late marriages and spacing between two kids need to be incentivised. Bureaucracy needs to work with the local village heads so couples are enumerated, tracked, counselled and helped to use the contraceptive of choice.

To tackle food insecurity, India needs a holistic approach that would work on the ground level and build partnerships with different stakeholders.

Javaid Iqbal is a management consultant and a Global Fellow at Brandeis University.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.