This article was originally published in Environmental Health News on August 13, 2018

The challenge is undeniably enormous. Huge economic pressures continue the exponential growth curve of plastic production, with no solutions capable of dealing with the problem at scale.

I spent two days at a Swiss ski resort at the end of July thinking with a group of experts on different pieces of the plastic problem, especially plastic in the ocean.

Ironic, I know. Alps vs. oceans. But the Alps once were ocean floors, so perhaps that is the circular economy.

The meeting was organized by the Klosters Forum, which describes itself as “a new platform that brings together disruptive and inspirational minds to tackle some of the world’s most pressing environmental challenges.”

The group they gathered included unquestionably “disruptive and inspirational minds” and it most certainly focused on one of the world’s “most pressing environmental challenges:” The nano, micro and macro plastic flowing off land into fresh and salt water.

(PS: It’s a problem on land too… more on that in another essay).

Health implications

Here at Environmental Health Sciences we knew this was a problem.

I gave a TED-style talk about it in 2016 in London’s famed Abbey Road Studio, at an event organized by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation just before the Brexit vote.

My emphasis was on the possible health implications. But it’s too easy to think about the atomized pieces (microplastics?) of this without seeing the full picture. That full picture emerged at the July Forum, because of the range of deep expertise that was present and because the sheer enormity of the challenge utterly resists any simple solutions.

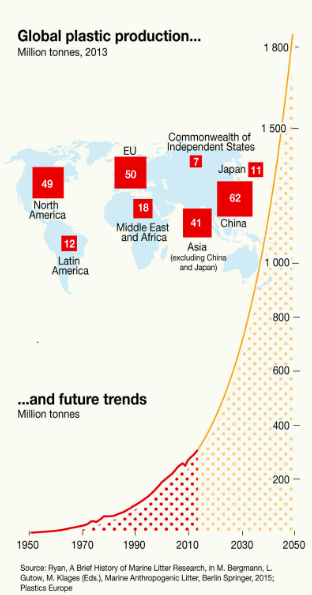

Plastic production trends are quintessentially exponential.

A headline-grabbing study published in 2017 concluded that half of the plastic ever produced was made in the last 13 years.

Above is a graph of the trajectory of plastic production predicted by the plastics industry. Some of that may be wishful thinking, but this trend is today driving investments in production capability by the world’s major plastic producers. It’s bad enough already.

Plastic debris even in the bottom of the Mariana Trench? A paper published in Sciencein 2015 concluded that “without waste management infrastructure improvements, the cumulative quantity of plastic waste available to enter the ocean from land is predicted to increase by an order of magnitude by 2025.” A ten-fold increase in just 10 years (now but 7 years away).

Scale of the problem

Peter Flynn, program director of the Klosters Forum, set the tone at the outset of the meeting when he led with a litany of plastic facts that had been compiled by Isabella Marinho, an undergraduate in Environmental Studies at the New School and an intern at Klosters.

Here it is (reprinted with permission):

Statistics on plastics and plastic related pollution

- 15 million tons in the 1960s to 311 million ton in 2014 and is expected to triple by 2050, when it would account for 20 percent of global annual oil consumption. (Antoine Frérot, CEO, Veolia) (World Economic Forum Report, The New Plastics Economy, 2016)

- The ocean is expected to contain 1 ton of plastic for every 3 tons of fish by 2025 and, by 2050, more plastics than fish (by weight). (World Economic Forum Report, The New Plastics Economy, 2016)

- Studies suggest that the total economic damage to the world’s marine ecosystem caused by plastic amounts to at least $13 billion every year. (United Nations Environment Programme)

- Each year, at least 8 million tons of plastics leak into the ocean – which is equivalent to dumping the contents of one garbage truck into the ocean every minute. If no action is taken, this is expected to increase to two per minute by 2030 and four per minute by 2050. (World Economic Forum Report, The New Plastics Economy, 2016)

- Plastic packaging generates significant negative externalities, conservatively valued by UNEP at $40 billion. (United Nations Environment Program)

- Packaging represents 26 percent of the total volume of plastics used. (World Economic Forum, Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey & Company)

- In 2016, the global production of plastics reached 335 million metric tons, with 60 million metric tons produced in Europe alone. (Statista)

- In a business-as-usual scenario of unchecked plastic-waste leakage, the global quantity of plastic in the ocean would nearly double to 250 million metric tons by 2025. (Ocean Conservancy and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment) Researchers estimate that more than 8.3 billion tons of plastic has been produced since the early 1950. About 60 percent of that plastic has ended up in either a landfill or the natural environment. (UN Environment)

- More than 99 percent of plastics are produced from chemicals derived from oil, natural gas and coal — all of which are dirty, non-renewable resources. If current trends continue, by 2050 the plastic industry could account for 20 percent of the world’s total oil consumption. (UN Environment)

- Only 9 percent of all plastic waste ever produced has been recycled. About 12 percent has been incinerated, while the rest — 79 percent — has accumulated in landfills, dumps or the natural environment. (UN Environment)

- Five countries – China, Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand – together account for between 55 percent and 60 percent of the total plastic-waste leakage. (Ocean Conservancy and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment)

- The use of plastic in Western Europe is growing about 4 percent each year. The potential saving of 80 million tons of plastic waste equals 1 billion barrels of oil or €70 billion. (Plastics Europe, October 2013)

- The amount of municipal waste produced on average by each European citizen is projected to increase from 520 kilograms in 2004 to 680 kg by 2020, an increase of 25 percent. (Paola Lettieri, Sultan M. Al-Salem, in Waste, 2011)

- Over 150 million tons of plastic waste in the ocean today. Without significant action, there may be more plastic than fish in the ocean, by weight, by 2050. (Ocean Conservancy and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment, Stemming the Tide: Land-based strategies for a plastic-free ocean, 2015).

- According to Valuing Plastic, the annual damage of plastics to marine ecosystems is at least $13 billion per year. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation estimates that the cost of ocean plastics to the tourism, fishing and shipping industries was $1.3 billion in that region alone. (S. Jennings et al., Global-scale predictions of community and ecosystem properties from simple ecological theory, Proceedings of the Royal Society, 2008, and in line with Stemming the Tide)

- In the United States and Europe, even with advanced collection systems, 170,000 tons of plastics leak into the ocean each year. (J. R. Jambeck et al., Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean, Science, 13 February 2015)

- Today, 95 percent of plastic packaging’s material value, or $80 billion to $120 billion annually, is lost to the economy after a short first use. (World Economic Forum Report, The New Plastics Economy, 2016)

- The recycling rate for plastics in general is even lower than for plastic packaging, and both are far below the global recycling rates for paper (58 percent) and iron and steel (70 percent to 90 percent). (World Economic Forum Report, The New Plastics Economy, 2016)

- In 2013, the industry put 78 million tons of plastic packaging on the market, with a total value of $260 billion. (Transparency Market Research, Plastic Packaging Market: Global Industry Analysis (2015)

Recycling won’t work

So the scale of the challenge is undeniably enormous. There are huge economic pressures at play to continue the exponential growth curve of plastic production. There are no solutions in hand today prepared to deal with the problem at scale. Lots of small stuff, often feel-good stuff, but nothing capable individually or collectively of solving it.

Recycling is simply incapable of managing this onslaught.

As Jane Muncke, director of Zurich’s Food Packaging Forum (Full disclosure: I am on FPF’s board) and an expert on plastics pithily observed “recycling is the fig leaf of consumerism.” It allows us to imagine our efforts are adding up to a solution. In reality they don’t even come close.

But it gives us psychological permission to continue on the current path – to continue with single-use plastics. And the problem will only become worse as we follow industry’s projected growth curve.

Don’t bet on bioplastics

If today’s bio-based plastics were to grow to a scale commensurate with the problem, they would have huge consequences for land management and food production.

They also almost invariably contain plastic additives necessary to achieve the material characteristics that manufacturers need. Many of those additives are linked to health problems.

And then there are the “Non-Intentionally Added Substances”, the NIAS, that plague all plastic production because the feed stocks aren’t pure and air pollution interacts with the plastic during manufacture to add unknown molecules to the mix.

There are new efforts to design plastics that break down on demand. These aren’t ready to go to scale and it would take a long time, if ever, for them to be produced at a volume sufficient to have meaningful impacts.

Today’s commodity plastics are simply too cheap. Plus, break-down plastics are still experimental. They might not work.

They, too, may become fig leaves.

Exponential growth is our enemy

I left the meeting with three inter-related thoughts:

First, simple solutions about recycling ocean plastics do not take into account the scale of the problem: how much is really out there, how much is macro vs. micro and the toxic dimensions of the problem as it relates to recycling toxic materials. They allow us to feel good but distract us from the problem.

Second, recovery from the ocean of micro and nano plastics is impossible, but increasingly we understand that this is where the problem lies, especially the toxicity issues.

Third, exponential growth is our enemy, and that’s what’s happening today and tomorrow.

Any solution that ignores current and future growth is, as Muncke puts it, “a fig leaf.” We will feel good as consumers, but our actions will not have measurable impact on the problem. And we can go on being feel-good consumers with single use plastics, adding to exponential growth.

Stay in the know with our newsletter

The enormity of the problem has led EHS to launch its new weekly newsletter, “Into the Plasticene” (free subscription here).

The newsletter, like our flagship “Environmental Health News” (EHN.org), aggregates media coverage in English from around the world.

Into the Plasticene will put stories in your inbox every Monday about the scope of the problem, efforts to develop (and scale) solutions, impacts on biota, and health implications for wildlife and people, as well as efforts by vested interests to distract and dissemble when they find their ox about to be gored.

Whatever we find that can inform your work on plastic, we’ll send to your inbox. Please give it a read.

Unlearning how to waste

American Beauties, Jan Staller

In the essay “American Beauties,” writer and sociologist Rebecca Altman traces the problem of plastic to a pivotal moment:

“The future of plastics is in the trash can,” the editor of Modern Packaging magazine, Lloyd Stouffer, argued in the mid-1950s to a group of industry insiders.

Stouffer had advocated for the industry “to stop thinking about ‘reuse’ packages and concentrate on single use. If the plastics industry wants to drive sales, he argued, “it must teach customers how to waste” (emphasis added).

Mr. Stouffer, you have created a global monster. May your descendants live in peace with its consequences. Or not. We’ve clearly learned Stouffer’s assigned lesson, abetted by the abiding cheapness of plastic. Now we have to unlearn it.

My reaction?

My head is in a vice as I peer into the Plasticene. And yes, my glass frames are plastic, as are the lenses.

Pete Myers is the founder and chief scientist of Environmental Health Sciences, publisher of ENH.org and DailyClimate.org

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.