Humanity does not have a good record when it comes to caring for signs of its past accomplishments. Napoleon’s gunners famously shot the nose off of the Sphinx, bombers in World War II destroyed many architectural triumphs, and ISIS fanatics have recently deliberately demolished priceless artefacts from Middle-Eastern civilizations. But this vandalism has largely affected remains of relatively recent civilizations, the past few millennia or centuries. But in Australia there are records from the longest-known sustainable societies, Aboriginal clans going back tens of thousands of years. These records are in the form of rock art, paintings and engravings preserved, often in shallow caves and sheltered spots, telling stories of secular and sacred life, and marking boundaries between clans. But this vast library, records of the society that was sustained for the longest period ever, is now threatened by resource exploitation. It is ironic that the death-throes of what is probably the least sustainable society of all time, scrambling after the last usable resources, can destroy this remarkable archive documenting a remarkable people.

Surely it is important to maintain as much of this rock art as possible and in the best condition. It is at the core of Aboriginal culture where visual and oral presentations are essential — they replace written language. Further, it provides spiritual support as well as practical visual information on the history, geography and biology of the sites. Some of the art is known to have survived for more than 35,000 years and naturally over time it has been degrading. Much damage has resulted from water erosion which is likely to increase dramatically if climate change increases rainfall and flooding. Damage also results from insect activities, especially nest building by wasps and trail construction by termites. When viewed in 2014, the Rainbow Serpent painting at Ubirr had four wasp species nesting on the paintwork. While some sites are protected by railings to prevent physical contact by visitors and by silica drip lines to divert rain water, most receive no care or supervision. We travelled together recently in Cape York and looked at many examples of Quinkan rock art, which prompted this discussion about how important it is to preserve rock art and how to facilitate its conservation.

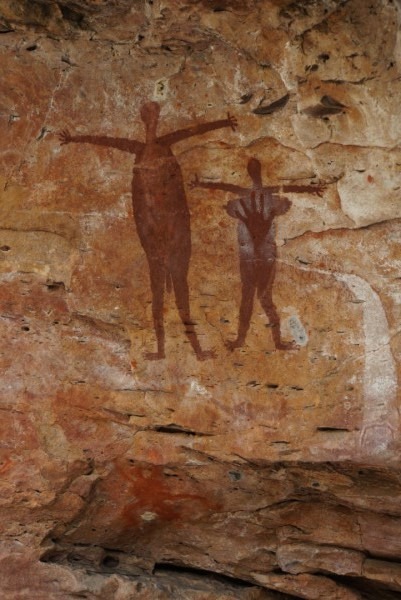

Quinkan paintings and engravings can be found in abundance in southern Cape York, the northernmost peninsula of Australia, on the massive boulder outcrops and caves scattered throughout the local savannah. Quinkan is a collective term for all of the different ancestor’s spirits which inhabit the landscape; the art includes them and secular figures of totemic plants and animals – the other organisms most important to the Quinkan people. While many of the paintings and engravings have been photographed and written about, it is certain that many others in the more remote regions await documentation. This is partly because of the prolonged separation of the original Aboriginal inhabitants and their rock art that resulted from their being chased from their land by the Palm River gold rush of the 1870s. It is thanks to a local landowner, Percy Trezise, that many art sites have survived. We were fortunate to be able to explore some of the Quinkan country of the Rifle Fish clan with his son, Steve, who is working to protect the rock art and maintain the interpretations and stories passed down to him by Aboriginal elders.

Much of the oldest Quinkan art now remains only as fragments of pigment, often below current ground levels. At Sandy Creek, for example, cultural deposits date to 37,000 years before present (BP) with fragments of ochre paints dating to 27,000 years BP. There are thousands of rock paintings that date to the early Holocene and while the reds and yellows may still be vibrant, other clay-based pigments have been degraded by water.

The Quinkan area is currently under consideration for World Heritage status and that is one major step forward. However, the practical maintenance of the art remains an issue. One question is whether rock art should be touched up as it fades. Redefining paintings is not unusual in areas where the original clans are still living and the stories portrayed in the art are still well known. This is the case with the world famous Lightning Man painting at Nourlangie which was last repainted in 1964 by Nayombolmi, a respected artist of the Badmardi clan. Problems arise where the original people have been displaced or the knowledge relating to the rock art has been lost. An ironic twist to the situation is that some visitors are disappointed if they find that paintings have been recently renewed and thus not untouched since the original work done millennia ago. This ignores that rock painting is a living process, so that some pictures are refreshed to retain the original information and others may be wholly or partially painted over in accordance with developments in the local Aboriginal culture.

Photo by Paul Ehrlich and Chris Turnbull

In parts of Western Australia some of these issues have been settled and close collaboration between Aboriginals and various other experts has led to the restoration and monitoring of critical sites. However, on a national scale, the areas over which rock art occurs is vast and it is often isolated, and the current number of sites is unknown, so the involvement of Aborigines, government agencies, academics and citizen scientists – plus serious funding – will be required to safeguard at least some modest fraction of the total. Finally declaring the Quikan area as a World Heritage Site would be very helpful.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/quinkan-art/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.