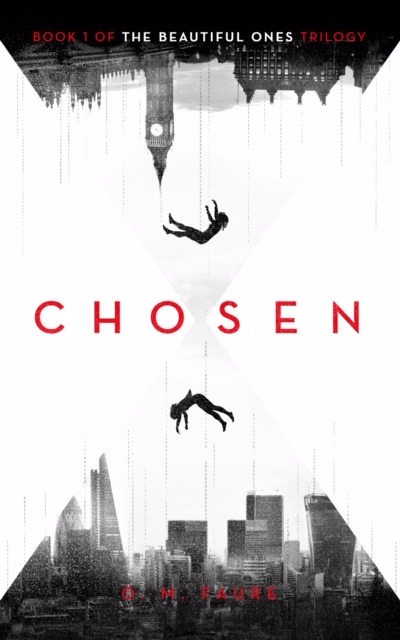

GH – You have written a fiction trilogy titled, The Beautiful Ones, that features human overpopulation as a central story element. What motivated you to write fiction that sheds light on the population issue?

Olfa Meliani-Faure – Back in 2016, I came across a UN report that said there could be 16 billion human beings on earth by the year 2100. I had a vague memory from high school geography classes of being told that fertility rates were capping at 0.8 children per woman and that generally speaking there wasn’t enough of us (Generation X) to finance the retirement of Baby Boomers and that the system would collapse if we didn’t make more children. But these half-remembered high-school days memories didn’t reconcile with what I experienced every day, as a Londoner: Tube corridors crammed full of commuters, huge crowds everywhere and a sense that there wasn’t enough to sustain us all, especially when Earth Overshoot day came earlier every year. So I started looking into overpopulation and realized that the number of humans on Earth had nearly doubled since the year of my birth. Something didn’t add up.

I researched the topic, reading articles and books like Life On the Brink by Philip Cafaro and Eileen Crist and I became convinced that overpopulation is in fact one of the root causes of the climate change emergency; everything we do is amplified by our numbers. The more I delved into overpopulation, the more I realized that environmentalists are aware of the issue but that it’s too complicated, emotional and sensitive to address, so it’s left out of the conversation. Fertility touches on such delicate areas of the human soul; the love of our children, our biological imperative to survive as a species, our religious beliefs. So, I can see why people would want to avoid talking about population as one of the factors of climate breakdown.

What motivated me to talk about it anyway was that overpopulation impacts on everything: the reason why there’s only 3% of wildlife left in the world today is because the 30% of mammal biomass on land are us and the 67% remaining are the cattle that we rear to feed ourselves. The reason there’s so much plastic in the oceans is because there are 7.6 billion of us using ‘just one straw, just this once, surely it won’t matter.’ Our rate of population growth are simply not sustainable and if we don’t discuss the impact our numbers have on the climate crisis, than we cannot begin to address it.

GH – As the 21st century unfolds, we are facing a perfect storm of existential threats that make human advancement and survival ever more uncertain. What part of this emerging scenario troubles you the most?

OMF – It’s hard to choose one, that’s probably why I decided to write about all the futures that worry me. The Cassandra Programme series will explore five scenarios:

- Overpopulation

- Catastrophic climate change

- World War III

- A viral outbreak

- Out-of-control capitalism

In a way, all these scenarios interact with each other. For example, overpopulation makes climate change worse. Catastrophic climate change causes wars. The rising temperatures and humidity increase the likelihood of diseases spreading. And out of control capitalism makes the poorest, more vulnerable to all these situations.

There’s a feeling of powerlessness and discouragement that takes over when you realize the size of the task ahead and the interconnected nature of all these challenges. You pull a thread and realize that the whole ball of yarn is attached to it and it’s a Gordian knot that’s become hopelessly complex over generations. To solve practically any issue, you must fix the system and changing a system is so hard that sometimes, people give up. That’s what troubles me. The sense of doom that takes over, making us feel like have no power to avert the terrible things that are coming. That’s why I create stories that involve time travel. I felt that straight-up dystopias were too grim. I wanted the readers to follow a person into the future with whom they could identify. Not a disenchanted, blasé character who’s always lived in a terrible future but rather a person from our own time period, who would be surprised by the awful turn of events and who would constantly challenge why things turned out the way they did.

So by introducing the time travel element, I hoped to create a sense that yes, in 2081, it will probably be too late to fix most of the issues I describe. But good news! It’s actually still 2019 and so there is still time to avert the worst. My hope is that the reader will close the book and think: ‘Right, what can I do today to prevent this future from happening?’

GH – How do we put humanity back on a course that is life affirming and worthy of our species?

OMF – Frankly, at this stage, I’m not entirely sure that our species is worthy anymore. We have done so much damage to the world around us. Part of the issue is that we think we are at the top of the pyramid, that the Earth belongs to us to do with as we please. This toxic belief is based on religious mythology, which depict the Earth as a gift bestowed on Man by God. So for millennia, we’ve behaved as if we own this planet, as if it’s a thing for us to exploit.

In reading James Lovelock, I have come to understand that we are part of a whole, we are only one species among many and that the Earth is in fact the life-support system that sustains us. And we’re suicidally poisoning it. We need to shift that obsolete narrative, change the story in order to change the course of events. If we can change the story we tell ourselves about the role humans play in the fabric of Earth’s ecosystems, our behaviors will follow.

GH – Is that vision possible as long as public policy favors profiteering over people and planet?

OMF – Sometimes achieving systemic change can seem impossible. Watching the news or reading about the state of the world, it can feel overwhelming and dispiriting. For example when you see a country like Canada declare a climate emergency in June 2019 and the very next day approve an oil pipeline. It can feel like we live in an absurd world where governments have forgotten that they’re supposed to protect the well-being of their citizens.

The social contract as defined by Hobbs, Locke and Rousseau is broken. Citizens consent to being ruled as long as the state looks after the interest of its people and works towards the greater good. With climate change, the question of whether our leaders respect the social contract has literally become life or death; will our governments choose climate action and the continued survival of their citizens over capitalism, power and money? At the moment the answer is not looking good; we’re seeing politicians who put their careers ahead of the country’s interests, states who capitulate to a handful of multi-national corporations, governments who surrender to a few powerful lobbies for money. This cannot work, in the long run. If the social contract is broken, if the state doesn’t even prioritize our continued survival, then citizens will no longer consent to be ruled by such governments. I think that’s why we’re seeing a rising tide of demonstrations across the globe. If things keep going as they are, with foreign meddling, dark campaign financing, heads of state flouting of the law, we may be the last generation that can still vote them out. Tomorrow, elections could become meaningless. There is a fascinating TED talk by Carole Cadwalladr which explains this in no uncertain terms.

We’re at a delicate juncture in history. We could be witnessing the death throes of democracy and an inexorable slip into authoritarianism. But equally, we could be the ones who change the course of events. We still have the power to vote for governments that can restore the social contract and save our democratic institutions.

GH – Jane Goodall says that to get to the heart of an issue, you have to put it in the context of a story. What is your take on this?

OMF – There’s a story I like which goes something like this: In the middle ages, an architect was walking along his construction site and asking the stonecutters what they were doing. The first one answered: ‘Are you blind? I’m chopping down chunks of stone with my chisel.’ The second one answered: ‘I’m making a living, I need money to feed myself.’ And the third one answered: ‘I’m building a cathedral.’ Clearly, the intent and the story of how you understand your life is going to make a difference to whether you do things, how you do things and how much effort you put into them.

I’ve worked for twenty years in change and transformation as a project manager and time and time again, I’ve seen dozens of corporate projects which try to change a process, a way of working, an operating model but it never works unless people believe in the change you’re proposing, unless they buy-into the narrative that surrounds the need for change. Yuval Noah Harrari touches on this in his excellent book Sapiens. In it, he explains that humanity evolved the way it did because we were able to create narratives that allowed us to work together towards a common goal. If we all believe in a story we invent together, then we are able to work as a group, within the mental blueprint created by that narrative.

That’s why, to me, the most important aspect of bringing about change is to win over people’s hearts. You can do that with stories because you can paint a vision of the future not with statistics and numbers but with emotions and situations that readers can project into. The question shifts from ‘Is it really 30% or is it in fact 32%?’ to ‘Wow, what would I do if this were my life and I had to make that choice to save my kids?’

That’s why I write fiction and not essays and articles: in order to touch people’s hearts. If I can change one person’s views or generate a debate or make readers aware of something they didn’t know before reading my books, then I will feel like I have accomplished my objective.

GH – Is there a story or a fictional character that resonated with you and encouraged you to ‘be the change’ in the course of your own life?

OMF – I became a feminist after reading Margaret Atwood in the early 2000s. I remember particularly reading The Edible Woman and Handmaid’s Tale and it’s always stuck in my mind as an example of how fiction can transform people’s understanding of the world. I also like stories where a person triggers change even though no one would have thought they could. I still have the stub of my ticket to see Eddie The Eagle pinned to my cork board where I can see it every day. I loved its message of ‘you fall down, pick yourself off the ground and try again until you succeed.’ And although I’ll out myself as a nerd, I have to admit that I love the Lord of the Rings and it’s message that ‘even the smallest person can change the course of the future’.

What I love the most though is when you see this message in the real world, in the awe-inspiring accomplishments of Greta Thunberg, Leah Namugerwa, Boyan Slat and Autumn Peltier, just to name a few. When I lecture at the university, I talk about these teenagers who are making a difference, in order to inspire my students to contribute to the change themselves. Yes, we are only one snowflake, only one tiny, fragile person but together, we will be an avalanche.

GH – What kind of stories do you believe we need to be telling given the uncertainty of the era we are living in?

OMF – I asked that question to Naomi Klein when she came to speak at the Southbank in London last year and I also had a really interesting conversation with an associate director at RAND at King’s College and both of them made a really good point that has stuck with me; they both said that we need stories that help us to imagine a better future.

When I was growing up, the future felt like a place of hope, a place of progress that would surely be better than the present. I lived in Germany when the Berlin Wall fell and it was a time when everything felt possible. We had grand declarations about the end of history, Mandela was freed and Apartheid ended. Surely we would solve world hunger next, bring about peace, conquer space, get flying cars?It was a naïve view of course, perhaps it had to do with the fact that I was young or perhaps it had to do with the stories we told ourselves then: about our countries being beacons of human rights, about the UN bringing peace through military operations, about the US being a land of opportunity that always had Right on their side. Surely the good guys had won the Cold War.

Then, somewhere along the way, we lost the sense that history should progress towards improvement, we stopped believing in the Manichean fairy tales we told ourselves. Military interventions turned out to be about oil, not human rights, the UN became impotent in an age of realpolitik, the US became the country of Trumpism, the NRA and Lehman Brothers. We removed the pink-hued glasses and perhaps we did need to mature and see the world like it really is. But in the process, we traded a narrative of perpetual self-enhancement, progress and good triumphing over evil for a narrative of cynicism, self-interest and mediocrity.

Now history feels cyclical, the future seems to be a place where everything we ever took for granted will be lost. So I think what we need are new narratives of hope; stories that bring back a vision of the future as somewhere that’s worth travelling to, books that rekindle in us our faith that we can change things for the better. Once I am done writing the Cassandra Programme Series, I will think about how to write utopias.

GH – Is gender equality a critical part of achieving a sustainable future?

OMF – As a woman and a feminist, I care deeply about gender equality and I think that women and men are just two sides of Homo Sapiens, equal in intelligence, capabilities and potential.

I believe that the gender-specific limits we put on ourselves are the result of millennia of narratives accreting on top of us like layers of dust and grime. Why should a woman not be able to do this or that? It makes no sense and we’re simply self-limiting ourselves because of traditions, religions, gender customs and other archaic views of the world. It’s clearly time to change this and liberate fifty percent of humanity’s potential, leverage fifty percent of our species’ abilities. We need to harness everyone’s skills if we’re going to make it through the 21st century alive.

That being said, I don’t think just putting women in charge in a patriarchal system is going to work. When you look at British female prime ministers for example, you realize that they were perhaps trying outman the men. We can’t just assume that a woman will be better than a man just because of her gender either. And similarly, I wouldn’t want to exclude the best person for the job just because of their genitals, so I’m uncomfortable with women-only initiatives, it seems to me that women have had enough gender discrimination for a lifetime, there’s no reason to do it to men now.

Perhaps the answer lies, once again, in a systemic change. The system we live in now is based on building blocks that have led us here. Those building blocks are all interlinked and they are what needs changing: patriarchy, out-of-control-capitalism, the narrative of man as owner of the Earth, these blocks have built the world we inherited. Rather than trying now to have a woman in charge in the system unchanged, what we need, I think, is to have the best person in charge in a system where the building blocks are: gender equality, sustainability and a narrative where humanity is part of an ecosystem.

GH – In many different instances, characters in your book must learn to move past their differences with others in order to ensure their survival. How do you think we as individuals and communities can do a better job of this in present day society?

OMF – All around the world, wherever we live, we are all noticing a rise of more self-centered political movements; there’s currently a return of nationalistic movements that want to exclude the other, the foreign, the “not us”. But the other side of this coin is also a rise of identity politics. I can see how groups who have been historically harmed and discriminated against would want to protect themselves and rise up. As a woman and a person of mixed ethnic background, I feel that need for change. At the same time, we are now, more than ever, facing extinction-level threats that demand that we all act together to tackle worldwide issues. For example bringing down CO2 emissions can only work on a global level if we all work together, rich and poor, Caucasian and People of Colour, men and women alike. The air we breathe won’t care about your sexual orientation or your religion when it asphyxiates you.

So yes, I write about characters overcoming their differences and coming together to fight life-threatening issues as a team. I think that we need unity and a common purpose, we need to start thinking at planet-level if we are to stand a chance of survival.

GH – Do you have plans to write more fiction? What is your current inspiration for this?

OMF – Yes, I’m currently writing the next three novels in my series: The Anthropocene trilogy. These books will tackle catastrophic climate change as a central theme. When I write, I take my inspiration from the ambient mood and current events. The wave of climate protests currently rippling through the world is a powerful muse. I march, talk to demonstrators, subscribe to the newsfeeds of climate protest organizations and I read non-fiction to inform myself about the consequences of climate change, for example, I am reading the IPCC report and excellent analyses such as This Changes Everything (Naomi Klein), The Uninhabitable Earth (David Wallace-Wells) or Six Degrees (Mark Lynas). When I do my research, I try to imagine what it will be like to live in that future, a future where we have done nothing to change course and we have to face the consequences of inertia.

Sometimes, I wish I could un-know the things I learn and go back to just enjoying life in ignorant bliss. There’s a sense of powerlessness and despair that take root, when you realize the gravity of the situation and the inadequacy of the response.

But I think that in a way, it’s that very climate anxiety that inspires me. It makes me want to do my part to change things for the better. Writing stories to pass on what I’ve discovered is the way for me to reclaim my sense of agency and to contribute to averting the futures I depict.

I hope it will work and that with my stories will help bring about the change we all yearn for.

Olfa Meliani-Faure is a London-based author and a consultant focused on transformational change. She has a master’s degree in International Affairs from the Tufts University Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Her books, endorsed by Paul Ehrlich can be found here.

Geoffrey Holland is a Portland, Oregon based writer/producer, and principal author of The Hydrogen Age, Gibbs-Smith Publishing, 2007.

The MAHB Dialogues are a monthly Q&A blog series focused on the need to embrace our common planetary citizenship. Each of these Q&As will feature a distinguished author, scientist, or leader offering perspective on how to take care of the only planetary home we have.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.