The deserts of the southwestern United States are well known for their high levels of biodiversity and endemism. An abundance of mountain ranges breaks this landscape into a series of isolated lowland valleys, many of which contain sand dune or wetland systems harboring unique species. Following leads from the citizen science database iNaturalist, our work in two of California’s desert valleys, the Carrizo Plain and the Fremont Valley, uncovered two formerly unknown species of scorpion which we recently described as Paruroctonus soda and Paruroctonus conclusus.

Both species specialize in alkali sink environments, areas within closed watershed systems where water flowing down from mountains creates highly saline and alkaline soils in and around an often dry water body. In this environment, scorpions are trapped between the harsh desert and the inhospitable dry lakebed in a relatively narrow band of suitable habitat. Alongside these scorpions, alkali sinks harbor a surprising diversity of halophytic, or salt-loving, organisms including specialized beetles, fish, amphibians, snails, plants, and more. Many of these species are endemic to only a single basin or a few adjacent valleys, isolated from their neighbors by the impassable desert mountains.

This pattern of unique isolated environments, while generating an impressive amount of biodiversity across the desert southwest, also leaves their inhabitants especially vulnerable to extinction. Alkali sink ecosystems exist in a fine balance between a lack and an excess of water, both of which threaten to alter the delicate conditions that many of their native species depend on. Drought may be especially damaging, as it simultaneously reduces the quality and shrinks the size of suitable habitats. As the climate in the southwestern United States continues to trend towards warmer temperatures and, in many areas, reduced precipitation, the future of alkali sink environments becomes increasingly uncertain.

A variety of more direct impacts on alkali sink habitats also threaten to bring their inhabitants closer to extinction. Mining for valuable minerals present in the salts that collect in playas can quickly degrade large areas of sensitive habitat.

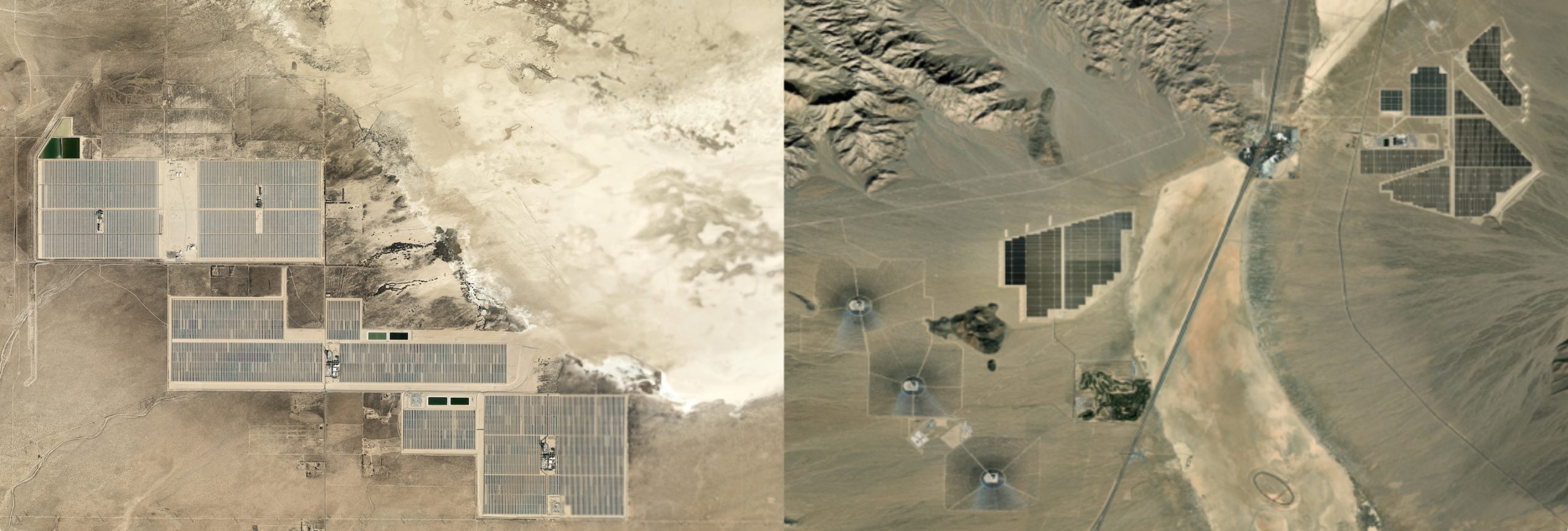

Furthermore, as predominantly flat and sunny desert regions, alkali sinks are often cleared for the development of solar energy facilities, which typically entirely and irreparably destroy the local ecosystem. Agriculture also poses a threat to these ecosystems. In California’s San Joaquin Valley, hundreds of thousands of acres of alkali sink habitat occupied by scorpions have been converted to farmland, making up for about an 85% loss in suitable habitat in the region. Lastly, as human populations in areas such as the western Mojave Desert and southern Nevada increase, urban expansion threatens to damage alkali sink environments, both by direct development and by overexploitation of limited water resources. Before its development, the Las Vegas Valley was dominated by a large alkali sink, less than 10% of which remains today.

Scorpions are some of the best subjects to study for insights into the ecology of the American deserts. The most diverse scorpion family in North America, Vaejovidae, is particularly prone to speciation, especially on isolated mountaintops, dune systems, and alkali sinks, which makes them excellent models for studying evolutionary trends across this region. Fluorescing brightly under ultraviolet light, many scorpions are relatively easy organisms to uncover, a trait that allows them to be exceptionally useful indicator species when monitoring the health and extent of unique ecosystems. One of the two species we described in our recent work, P. conclusus, is only found in an extremely small stretch of habitat (approximately 2 km by 100 m) alongside the southern shore of Koehn Dry Lake. It is plausible that one of the many threats to alkali sink species could drive this scorpion to extinction within a short time. Furthermore, it is likely that such a threat, whatever it may be, will be similarly damaging to every other unique species that inhabits that ecosystem, resulting in their demise. Studying and protecting rare scorpion species is much more important than conserving the scorpions themselves—by understanding their evolutionary history and ecology, it becomes possible to identify the most biologically unique environments and prioritize their preservation alongside the rest of the biodiversity they harbor.

As the decline in biodiversity accelerates across the globe, it becomes increasingly urgent to prioritize the preservation of wildlife and wild spaces. The two species we described in 2022 represent a tiny fraction of the likely thousands of undescribed species remaining in the southwestern United States, which itself is one of the most well-studied regions of the globe. Among scorpions alone, we have observed dozens of undescribed species and continue to locate more far faster than they can be easily cataloged. It is likely that several scorpion species, along with the entire unique ecosystems that gave rise to them, have disappeared underneath the development of cities such as Las Vegas or Palm Springs before they could ever be studied. If we are to try to prevent as many such losses as possible from occurring, the importance of expanding biodiversity research and widespread conservation can not be overstated.

Prakrit Jain is a student at the University of California Berkeley studying ecology and evolutionary biology. His primary interests are the evolutionary biology of scorpions, desert ecology, and biodiversity conservation.

Harper Forbes is a student at the University of Arizona studying ecology and evolutionary biology. His work focuses on the taxonomy and ecology of US scorpions and wildlife conservation.

Their original paper was published here and also featured in The Guardian.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.