“Folks, we are facing ecological crises!”

To a casual observer who nods in agreement, this proclamation in a plural form obviously means the heatwaves, wildfires, extreme storms, megadroughts, and megafloods that flash across mobile devices and TV consoles in this first-century quarter of the new millennium. But to a trained scientist in the environmental sciences, this same plural form means the broader pressing issues of the Anthropocene: climate change, biodiversity loss, nitrogen deposition, land degradation, ocean acidification, and the crossing of other boundaries.

Why did our casual observer only think of the symptoms of one crisis? Because that’s all she heard in the news, all she learned from books and lectures, all she casually chats about with friends and family.

To her, climate change is the single great environmental problem of the 21st century. All other ecological issues, species extinctions to pollutions, huddle under this single, all-encompassing umbrella.

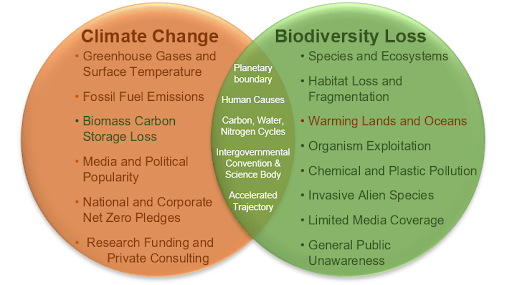

But if only our casual observer met our trained scientist who can tell her this conflation of issues is simply not true. Human activities have done more than release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere to trap heat and raise surface temperature. Through farming, fishing, building, mining, shipping, poaching, and polluting humans have also caused another distinct but mutually reinforcing global crisis to climate change: biodiversity and ecosystem loss.

Climate change as the main environmental crisis

Why does our casual observer overlook these other crises? Why did she ignore it as former IPBES chair Robert Watson pointed out?

Because she grew up with climate change in the background all her life.

She read about the Exxon and Shell scientists who learned early of the greenhouse gas effect since the late 1970s and James Hansen testifying to Congress in the late 1980s and she heard about the UN charters and conventions and assessments on the subject. The colloquial term of climate change was easy to understand (or deny) with its smooth upward sloping Mauna Loa graphs of atmospheric gases in parts per million, rising surface temperature across century time scales, and pathway scenario modeling, and satellite images of shrinking ice sheets. And its narrative is easy to explain with usually one villain to blame – fossil fuels, or an easy fix like CFCs in the ozone layer problem.

Our casual observer even lived it, heard it, or watched it with triple-digit summers and unpredictable, intense storms. When once-in-a-century cyclones arrive yearly, when corporations and governments join the green movement with pledges of net targets to zero, and research funding pours in for more climate studies, our casual observer and many others only know of one environmental problem.

So, she fights hard against the denialists, online and offline, and marches on streets with signs of “No Planet B!” Yes, to our casual observer this is the one serious emergency with real human impact and toll. The melting poles, rising seas, drying crops, recurring droughts, third-world famines … all this and more to come are due to the main environmental crisis of our times: climate change.

Biodiversity loss as a distinct but mutually reinforcing crisis

However, our casual observer rarely looked beyond her city and suburban limits. She does not lament over the slowly decaying soils, water sources, and arable lands at the edges of the countrysides.

She does not see the green algal blooms or red tides from agriculture runoffs. She rarely dives into overfished marine coastlines to see coral reefs and kelp forests degrade. She did not pause to hear the silence in the middle of forests where generations ago diverse insects buzzed, frogs croaked, trees towered, birds soared, and wild plants flowered.

Few studies endure in the news like the IPBES’s Global Assessment report regarding non-climate issues of land and sea use changes, overexploitation, pollution, and invasive alien species that all drive biodiversity and ecosystem loss.

While extreme weather events easily move casual observers, species extinctions, forest diebacks, and ocean dead zones occur without a sound or video.

Our casual observer was told to recycle, reuse, and reduce waste to morally protect the environment and not because of the ecosystem services she and all homo sapiens critically rely on for survival: the pollination of crops, cultivation of the soil, control of pests and pathogens, the regulation and flow of freshwater, air quality, access to medicines, protection from storm hazards, and even regulation of the climate.

Yes, no one connected the dots for our casual observer that biodiversity and ecosystems regulate the climate through carbon, water, and nitrogen cycles.

She hardly knows her diet and food wastes trigger both crises, too. She blames coal plants and oil rigs because of CO2 emissions but not its supply chain that drill, mine, excavate, and pollute pristine ecosystems.

While she screams to cut back fossil fuels, imagine if she knew the degradation of ecosystems that capture over 50% of annual anthropogenic emissions through natural carbon sinks in vegetation and oceans requires even larger fossil fuel cutbacks.

While she praises clean energy, imagine if she knew its ramped-up narrow focus can be detrimental to biodiversity: land-clearing solar and wind farms and bioenergy crops; monocultured trees in non-native biomes; deep-sea mining for earth metals in energy batteries and photovoltaics; and toxic waste from retired ELVs in a throwaway economy.

Nature and overshoot crisis

But we hope our casual observer can correct this myopic vision of environmental issues. With a wider, comprehensive lens, she can see climate change and biodiversity loss are two of several recognized planetary boundaries.

If there is an umbrella crisis, it would be the nature crisis where humans have waged a senseless and suicidal war against as the UN Secretariat-General asserted.

With such an expansive worldview, our casual observer can become a conscientious observer to break away from climate-centric and human-centric focus. Maybe then she and her peers can tear down the silos of science departments, peer-reviewed journals, media conglomerates, research funders, corporate consultants, and geographic borders to tackle this one global crisis of ecological overshoot.

So, we hope our conscientious observer follows the intergovernmental conventions UNFCC and the Center for Biological Diversity (both to turn 30 years old in 2022) as well as the IPCC and IPBES, who assess both crises. Let’s hope she and her kind remember the Paris goals and not forget the Aichi targets. Let’s hope they read the IPBES and IPCC assessments as well as those by the UNEP, WWF, IUCN, BGCI, and by other environmental groups that illuminate our nature crisis.

As dire as the approaching Arctic to Antarctica climate tipping points are, so will our conscientious observer shudder at an accelerating extinction rate which is now higher than for the last 10 million years.

Shared and Distinct Traits of the Dual Crises

Moreover, we hope that conscientious observers will grow in scale and scope. With conscientious media companies, environmental coverage can be balanced across the spectrum, with weekly quotas of climate, biodiversity, and pollution stories instead of flooding airwaves with only sensational wildfires and floods. Then the term biodiversity can become a colloquial term born from quieter stories: starving manatees, disappearing insects, depleted wetlands, nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer runoffs…

With conscientious peer reviewers, a revolution-like “p-value misuse and negative results movement” can unleash on scientific journals where environmental articles must include the multidisciplinary treatment of all interacting issues of the nature crisis – and not just the narrow emphasis on atmospheric gases and surface temperatures in a vacuum.

With conscientious business leaders, larger goals beyond net carbon targets can be raised that include land use targets, ecosystem service financing, and natural capital accounting.

With conscientious policymakers, dynamic and adaptive policies can emerge for spatial planning, fishery and forestry reform, agriculture management, blue carbon restoration – crossing borders, and spanning government levels. To forge sustainable solutions, this should include all actors, from multi-national corporations to indigenous peoples.

And with a conscientious general public, daily conversations about this 21st-century nature and overshoot crisis can engage and motivate change from trained scientists to casual observers.

Parfait Gasana is an economics-trained data and research analyst from the Chicago area, with passionate interests in public infrastructure, energy, environment, empirical methods, and data analytics. Active on GitHub and StackOverflow communities, he is also an avid reader of climate and biosphere news and studies and creates environment-themed data projects, including R and Python analytical reports and environment SQL databases.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.