Climate science and the media have tended to focus on terrestrial ecology to solve the climate crisis. They have ignored the significance of some of the smallest and most plentiful contributors to Earth’s climate and ecological balance.

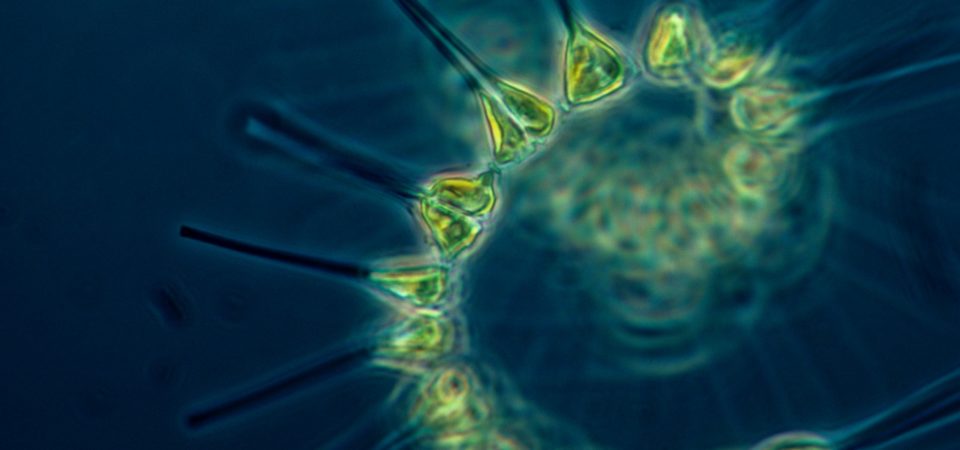

We know that ocean acidification makes it more difficult for mollusks and corals to form their shells. It also makes it difficult for plankton (tiny marine plants and animals) to form protective shells. Diatoms produce the greatest proportion of plankton biomass in the world ocean. It was originally thought that the silica-based shells of diatoms would not be affected by current levels of acidification. That turned out to be a short-term and wrong view of the issue. Diatom numbers were declining. In a study published in Nature on May 25, 2022, scientists at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel showed that diatoms were seriously threatened. On a global scale, there was a different dynamic discovered that might explain the reduction in the total diatom population.

Dr. Jan Taucher, the first author of the GEOMAR study said,

“… (diatom) decline could lead to a significant shift in the marine food web or even a change in the ocean as a carbon sink… Already by the end of this century, we expect a loss of up to ten percent of the diatoms.”

If this trend is carried to the year 2200, more than a quarter of the global diatom population could be lost. That would pose a problem equivalent to removing the oxygen production and carbon sequestration of the entire Canadian boreal forest. In other words, a major die-off of phytoplankton could potentially lower atmospheric oxygen levels by as much as 20-25%.

A keystone for life

Plankton is a keystone to life on Earth. Plankton productivity plays a major role in the planet’s carbon cycle, marine biodiversity, the human food supply, and the air we breathe. Photosynthesis by phytoplankton (plant plankton) defines the planet’s atmosphere. Between 50-80% of atmospheric oxygen comes from marine and aquatic plants. That’s more than the oxygen production from all the forests and green plants on land combined. Most phytoplankton are so small they are invisible to the naked eye. A single cubic centimeter of seawater can contain millions of these tiny organisms. For this reason, plankton was overlooked for centuries. The vital role of phytoplankton in the survival of life on land has now come to the fore.

A single species totally altered the course of evolution on Earth. Nearly three billion years ago, cyanobacteria (an early form of phytoplankton) completely changed the Earth’s bio-geochemistry. Photosynthesis established the carbon/oxygen cycle, and from there, all oxygen-breathing life evolved.

In addition to its role in the carbon/oxygen cycle, phytoplankton form the foundation of the marine food pyramid. What they lack in size, they make up in numbers and variety. There are over 5,000 known species of phytoplankton. Zooplankton (animals) feed on phytoplankton. Ocean grazers feed on them. Further up the food chain are fish, including those that find their way to our dinner plates.

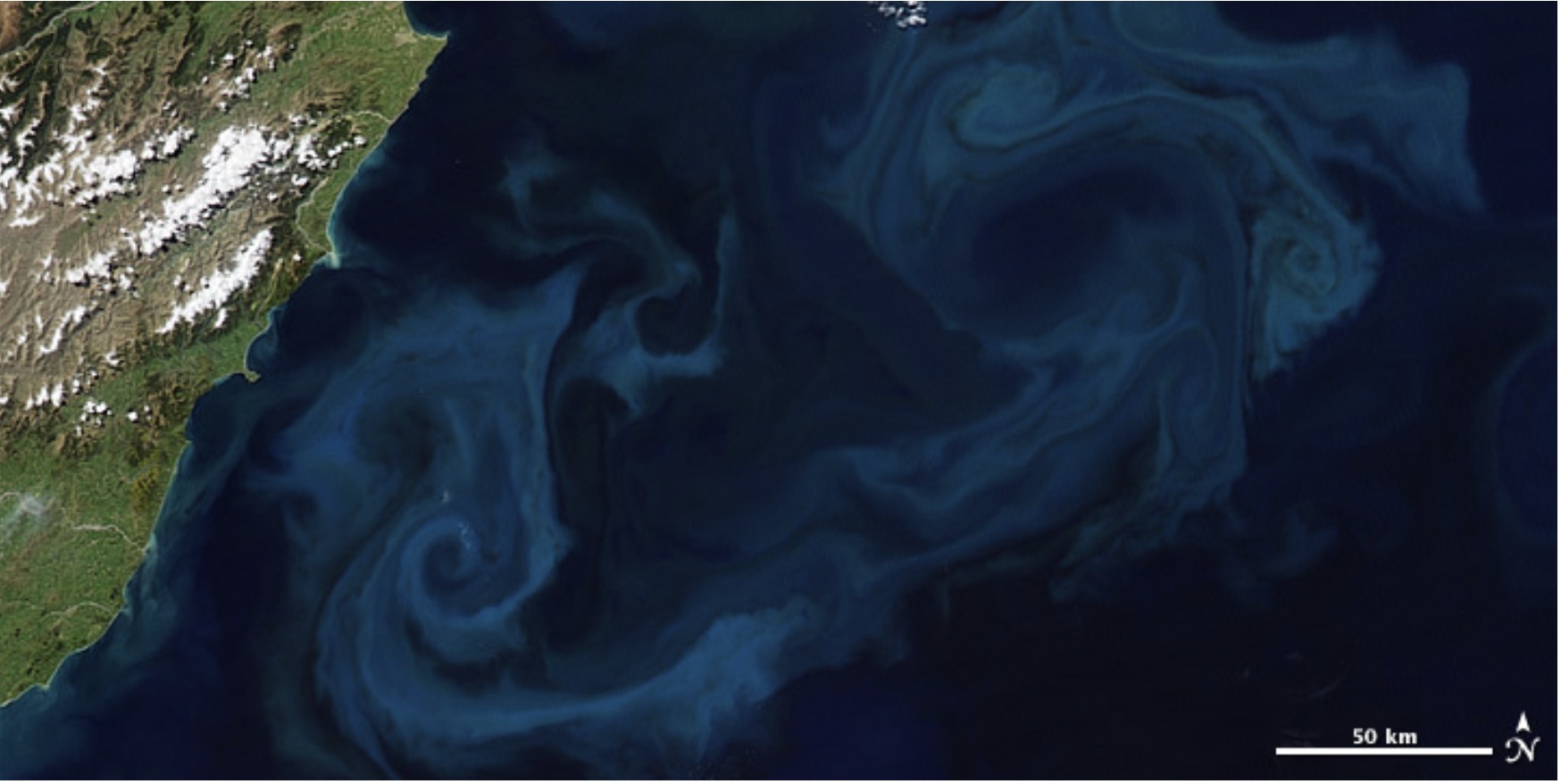

Most phytoplankton do not swim; instead, they drift with the current. They grow and multiply with the seasons. Some of these blooms can become so enormous they can be seen from orbiting satellites.

These blooms can become so dense they consume all the surrounding nutrients. When all the nutrients have been consumed, there is a massive die-off. In some species, a die-off becomes toxic, a condition commonly known as red tide. If the die-off is large enough, the decomposition may consume all the oxygen in the water, creating anoxic dead zonesdevoid of aerobic life.

Worldwide, phytoplankton transfer about 10 gigatons of carbon from the atmosphere to the deep ocean each year. A reduction in the phytoplankton populations would leave more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere; this could lead to more warming and higher global surface temperatures.

The most common phytoplankton are cyanobacteria, silica-encased diatoms, green algae, calcium carbonate-coated coccolithophores, and dinoflagellates. Phytoplankton numbers and their distribution are determined by four major factors: nutrients, temperature, pH, and sunlight. All four of these factors are changing faster than most phytoplankton species can tolerate.

Ocean currents are the major influence on weather patterns. As the marine ecology changes, the land environment also changes. A great closed-loop conveyor belt of marine current distributes nutrients around the world. Ocean currents change when water density is altered by changes in salinity and temperature. Climate change alters both factors: as the Earth warms, the distribution of nutrients trends toward the poles, moving plankton and fisheries with it.

Some species can adapt, others can’t

Marine plants have optimal temperature preferences. Different species have lesser or wider ranges of resilience to changes in their environment.

Some species are more adaptable. Some phytoplankton can fix nitrogen and live in areas with low nitrogen levels. Others can’t thrive where nitrogen levels are high. Furthermore, plankton have different tolerances to plastics and plastics by-products. The availability of iron is a similar limiting factor. The broad portfolio of species in the past has given the marine ecosystem resilience to a changing environment. But today’s extraordinary ocean acidification causes that portfolio to be less diverse and makes the marine ecosystem much more vulnerable to a rapidly warming planet.

Coccolithophores are phytoplankton with calcium-carbonate shields covering their bodies like circular shingles. These shingles capture and store carbon while the organism is alive. When the organism dies, that same carbon becomes part of another kind of sequestration that takes place on a geologic time scale.

When coccoliths die, their carbon skeletons settle as marine snow on the ocean floor. In some places, these sediments are thousands of feet thick. Over millions of years, the carbon in the sediment forms chalk. The white cliffs of Dover in England are a good example. The movement of tectonic plates and erosion then releases the carbon back to the surface, completing this phase of the carbon cycle. That’s the good news.

Ocean acidification harms phytoplankton

The bad news is that calcium-carbonate phytoplankton and silica-shelled diatom populations are threatened by ocean acidification. The ocean is currently absorbing about a third of anthropogenic carbon emissions. This excessive absorption of ancient fossil carbon increases the formation of carbonic acid, which lowers the ocean’s pH beyond its normal state. That is important because the ocean pH has dropped by approximately 30% since the industrial revolution and continues to decline. The more acidic the ocean becomes, the more the calcium-carbonate in the phytoplankton fails to form, or is eroded. This is thought to be responsible for the overall reduction in plankton population numbers. Should this lead to a major global die-off of coccolith phytoplankton, the loss in atmospheric oxygen would be approximately equal to eliminating the entire Amazon rainforest.

The bottom line is that ocean acidification is a significant stressor for marine photosynthetic plants. That, in turn, impacts the larger planetary carbon/oxygen cycle as it disrupts the balance of oxygen available in the atmosphere.

The carbon/oxygen cycle on Earth would be disrupted by the decline in phytoplankton. Even this smattering of information indicates that the entire marine ecosystem is in imminent danger. Global populations of the most common and influential species of silicon and calcium-carbonate phytoplankton are declining. Research points to the probable connection between anthropogenic ocean acidification and the decline in phytoplankton. What we know thus far should raise concern and stimulate further research. The significance for human survival over the next half-century and beyond is clear.

Further reading

Taucher, Jan (et. al.), May 2022. Enhanced silica export in a future ocean triggers global diatom decline. Nature

Petrou, Katherina and Daniel Nielson, August 26, 2019. Acid oceans are shrinking plankton, fueling faster climate change. The Conversation

Bralower, Timothy and David Bice, December 18, 2022, Acidification Effect on Plankton, Penn State University (Earth103: Earth in the Future)

Chandier, David L., June 4, 2015. Study: Ocean source of greenhouse gas has been underestimated. MIT News

Cameron, Petra and Philippa Kearney, May 23, 2019. Plastic poisons ocean bacteria that produce 10% of the world’s oxygen and prop up the marine food chain. The Conversation

Chu, Jennifer, July 20, 2015. Ocean acidification may cause dramatic changes in phytoplankton. MIT News

Morel, Francois, December 18, 2022. Effects of Ocean Acidification on Marine Phytoplankton. Carbon Mitigation Initiative

Doug Smith is an environmental scientist with 30 years of experience with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a Senior Compliance Investigator. He taught and monitored “environmental management systems” under domestic and international operating standards. From 1996 – 2005, he was an EPA liaison to the United Nations and the World Bank Institute. Together, they helped nations develop their own environmental protection programs. Doug also served on the Board of Directors for the Seattle Chapter of the United Nations Foundation. He owned an international adventure travel company for thirty years, exploring many ancient civilizations, cultures, and remote regions of the world. His experiences with multi-national corporation management and the development of environmental programs give him a unique perspective on sustainability, human behavior, and the multiple existential crises threatening global civilization.

Doug Smith is an environmental scientist with 30 years of experience with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a Senior Compliance Investigator. He taught and monitored “environmental management systems” under domestic and international operating standards. From 1996 – 2005, he was an EPA liaison to the United Nations and the World Bank Institute. Together, they helped nations develop their own environmental protection programs. Doug also served on the Board of Directors for the Seattle Chapter of the United Nations Foundation. He owned an international adventure travel company for thirty years, exploring many ancient civilizations, cultures, and remote regions of the world. His experiences with multi-national corporation management and the development of environmental programs give him a unique perspective on sustainability, human behavior, and the multiple existential crises threatening global civilization.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.