This is a transcript of a 20-minute presentation given by Lucy Weir, Ph.D., at the Social Health Education Project (SHEP) Earth Aware and Cork Environmental Forum, Ireland, on January 8, 2020.

Bold text is slide presentations.

“We cannot keep drifting apart into two separate tribes with a separate set of facts and separate realities with nothing in common except our hostility for each other.” (Mitch McConnell).

I’ll get this out there before we go any further: the idea of there being no ‘them’ and ‘us’ is a challenge – even for me, and I’m proposing it! It requires a radical reassessment of how one approaches situations. It provides a radical re-set. It is a powerful tool for taking on the ecological emergency as an emergence, an urgent and critical matter that calls for our full attention and reminds us that it is HOW we pay attention, or realize, that matters.

I will not be discussing whether or not the ecological emergency exists but I will at least clarify what I mean by the ecological emergency because it’s a broader definition than most. I define the ecological emergency as a phrase that encompasses both the environmental crises of pollution, deforestation, desertification, mass species extinction, and climate change, and also the human attempts to conceptualize this impact. This linking of anthropocentric, human-caused, changes in both atmospheric (or climate) and ecological (or terrestrial) systems is not new, but it is also, sadly, uncommon as a representation in media and public discourse. Including how we respond as part of the definition is almost unheard of.

From turning on the light to turning the ignition in your car, from buying bread to building bridges, each individual act may be statistically and morally insignificant, but when you multiply them millions and billions of times, they add up to the ecological emergency. Coral bleaching isn’t just happening over there, it’s happening because of what we, you and I, do, however apparently trivial the act.

The philosopher Timothy Morton came up with the phrase “ecological emergency”. My definition is slightly different. I include not just what is emerging to demand our immediate attention – from increasingly violent storms and droughts to the mass migration flows caused at least in part by these phenomena. I include the emergence of that awareness itself. I also include the intersection of physical and social reality as it emerges into our awareness. If physical reality includes ecosystem fragmentation, threatening natural systems’ resilience, then social reality includes attitude polarization and increased extremism. What is emerging urgently and critically, in our own awareness, is that these – the internal and the external, the social and the real, the “us” and the “them” – are not separate processes. They are interconnected. Indeed the urgent emergence of our own awareness of interconnectedness is a kind of key to how we can respond to the emergency.

By realizing, literally and metaphorically, that none of us is separate from either cause or response, or from one another, that we are all entirely enmeshed and interconnected in this process, we can begin to consider our options.

Respect for Nature is a life-centered theory of environmental ethics. It consists of three interrelated components. First is the adoption of a certain ultimate moral attitude (respect for nature). Second is a way of conceiving of the natural world and of our place in it, which makes the attitude appropriate to take towards Earth’s natural ecosystems and their communities. The third is a system of moral rules and standards for guiding our treatment of those ecosystems and living communities. The theory is structurally symmetrical with a theory of human ethics based on the principle of respect for persons.

My Ph.D. research began under the late Dr. Tom Duddy with an exploration of Paul Taylor’s theory of Respect for Nature outlined in the book of that name. My epiphany came, gradually, as a result of Tom’s untimely death, and my having to find a new supervisor (I wanted to pause my research to grieve but I had no money and would have lost my grant).

Realization as agency is a theory of ecophilosophy. It consists of three interrelated components. First is a way of conceiving our species as entirely enmeshed with all other systems in the more-than-human world. Second is the realization of what this enmeshment implies about our capacity to act as agents (and moral agents) in the world: we have no free will, in the traditional sense, and therefore we are unable to act morally in the traditional sense. The third is the understanding that the very act of realization is itself the source of our agency. In Zen terms, this is ‘the backward step. This (following Taylor) means there is a certain appropriate attitude to take or attune to, as a result of this realization, and that is an attitude of compassion.

I completed my Ph.D. thesis under the supervision of Professor Graham Parkes. Graham encouraged me to turn from environmental ethics, which is essentially an analytical approach, to a phenomenological understanding of what was going on. He introduced me to the work of Dōgen Zenji, a thirteenth-century Japanese Zen Master and author of the Shōbōgenzō, The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye.

”To study the Buddha Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away. No trace of realization remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly.” Dōgen Zenji

Dōgen Zenji turned the traditional idea of working towards the Buddhist notion of enlightenment on its head. His admittedly highly complex, challenging, and often paradoxical writings explore the idea that we are already enlightened, all of us, human and more-than-human, from Donald Trump to Greta Thunberg to the polar icecap to the Sargasso Sea. What we need to do, however, is realize this, to study, to practice-realization. We are all Buddha-nature, but until we realize this, we cannot ‘forget the self’.

“When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point; for the place, the way, is neither large nor small, neither yours nor others’.” ( Dōgen Zenji).

“Action alone is thy province, never the fruits thereof; let not thy motive be the fruit of action, nor shouldst thou desire to avoid action.” (M K Gandhi’s translation, The Bhagavad Gita)

By combining the research I had done into Taylor’s respect for nature, environmental ethics, evolutionary biology, systems theory, and Dōgen Zenji’s (and other East Asian) philosophies, it became clear that responding to the ecological emergency requires the practice of realization. This, in turn, points us towards attunement to a particular attitude. Our own attitude is, if you like, our own way, the HOW of what we do. This is rather like shifting focus from goals, or ends – we want to live in harmony with nature, for instance – to means, or method: it is how we do things that count, not the outcome.

In The Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna, the warrior prince, is advised by his charioteer, who is actually the god, Krishna, not to concern himself with the outcome. This seems to me good advice and echoes Dōgen Zenji’s focus. Instead of concerning ourselves with what is going on externally, we focus, instead, on our own attitude, or way, or doing. This is rather like shifting focus from ends to means. If the end, or goal, is not something over which we have any control, it is therefore not the element on which we need to focus. Rather like evolution (or, as I will argue, enlightenment) itself, there is no goal, no end, towards which the process aims.

Paul Taylor concluded (after Kant) that ‘respect’ was the most reasonable attitude to take in response to understanding that all living entities have a ‘good’ of their own. In realizing our enmeshment, compassion is the most reasonable attitude to take.

It’s clear that in the context of our evolutionary biology, we, Homo sapiens, do not stand atop an evolutionary pyramid, any more than viruses lie at some crude, broad base. A better metaphor than an evolutionary ladder (or any of the Judeo-Christian, or Graeco-Roman, imagery of man atop the chain of being, below only angels and God himself) is to think of evolution as a bush, or tree. We are simply evolving, along with everything else, and if we have any ‘quest’ then it is to avoid annihilation – in other words, to move away from our own demise rather than to move towards some shining pinnacle of a future good.

Individually, of course, we cannot avoid death. When you consider the evolutionary push away from annihilation, this fact becomes important. It gives us further fuel for the thought that rather than concerning ourselves with personal survival – a fruitless task beyond the three score years and ten – we must consider what we might do to avoid species annihilation. More, we must consider whether or not the limits to our annihilation end at our species boundary. It takes only a little thought to realize that these limits are illusory.

Locust swarms, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and so-called ‘plagues’ are all, also, reactions. Physical reality is a process of reaction. Human or social reality (culture, language, synthesized products, and so on) are also a process of reaction. The two interact. Individually, we react. Unless we “wake up” to right now, and then we realize!

Most of what happens in the universe follows this pattern: there is an action, and there is a reaction. In Yoga, this process is called Karma. The word has no positive or negative connotation. It simply means ‘action’.

Our lives are action and reaction, individually and culturally, in a kind of snowball effect. We all react – unless there is awareness, or what is termed realization. The realization is the process by which we become aware of what is going on while it is going on. As soon as I draw your attention to it, to what is happening right now, in your own life, internally and externally, you realize. Realization, in effect, allows us to take what is called in Zen ‘the backward step’.

What existence offers us is the possibility of awakening to our own awareness, of realizing that we are not in this flow because we are this flow. We are inseparable from it. This means that everything we do matters. But since we are largely at the mercy of this flow, rather than in control of it, we need to become aware of the kinds of acts that matter.

Dōgen Zenji was quite clear that there is nothing in existence that is not Buddha nature. This is similar to saying that there is nothing that is not a part of the flow of existence. Buddhism also recognizes that there is an element to this flow that is inherently compassionate. In a sense, the ground of being, or existence itself, is compassionate.

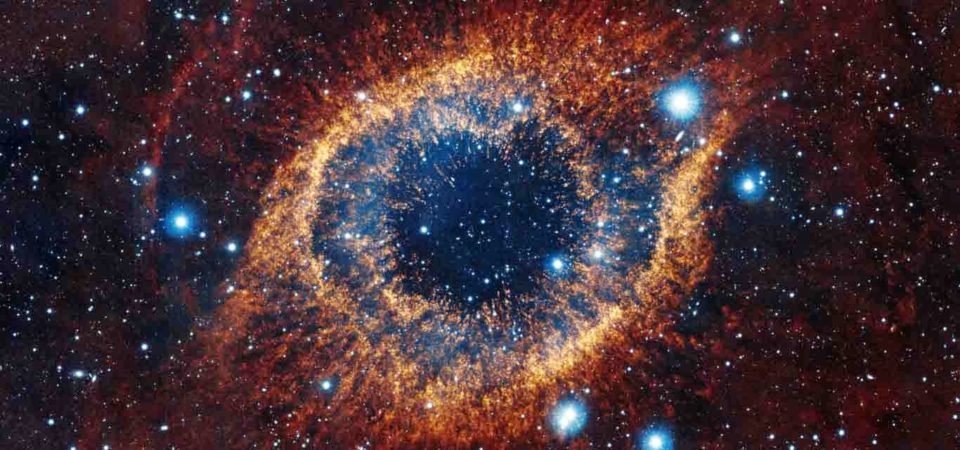

Consider the universe in a Poincarean, mathematical sense as a series of equations working themselves out. The fact that the equations of the universe, as elements in reaction, or energetic systems in the process, do not work themselves out in a simple, linear form, but instead are probabilistic, complex, unpredictable ways, means that the universe itself does not simply begin at A and end at B. Instead, it continues through, to our minds, almost infinite time and space. It offers all the possibilities provided by the vastness of this space and time, for the possibilities of planets, stars, galaxies, and even ourselves, maintaining existence over time (Scott Sampson has done interesting work on this). In our own case (and perhaps also in others, though we have done little enough research) it offers the possibilities provided by consciousness, including awareness, and therefore realization (or, in the Buddhist sense, enlightenment). There is a kind of compassion in this. There is more compassion in the possibility offered by existence, after all, than by non-existence.

When we practice realization, we become attuned to compassion. We didn’t choose our family, our place, or the nature of our upbringing or education. Neither did anyone or anything else! I didn’t choose to the death of my first supervisor (and nor did he), nor any of the things that happened to me as a child that caused me to act in ways that were and are destructive. The most reasonable attitude to take to my own situation, and to the situation that is emerging into my awareness, is compassion.

There is only one act that we can perform that creates a shift in how we relate to this existence. That is the act of stepping back, of becoming aware, of realization. Our realization is our agency. Our realization is our being aware of what is going on while it is going on.

When compassion arises as a rational response to my awareness of my own and all enmeshment, then possibilities arise that otherwise remain latent, or hidden. I begin to see options for action. I am still enmeshed, but my enmeshment has shifted. I can now see what needs to be done, not by me, as much as by compassion, or by love. I do not act independently any more than I did before awareness arose. But I am now attuned to compassion, and therefore love, the thing that is most loving, most compassionate, does itself through me.

It is the attitude of all of us, even those of us who think that we are on the side of the angels, that matters. If we, as a species, are to come into alignment with the flow of the rest of existence, including living existence, so that our species can explore its potential in the fullest way possible, and mitigate at least some of the impacts it has so far had, largely harmful, on the rest of the systems that created and sustain us.

My suggestion is that we open to the flow of all that is going on but realize that we don’t control that flow, any more than we control the flow of our thoughts, or what genes we have. By learning to do this, we will be at a place where we are ready to take on the reality of how

we can respond to what is going on, including the ecological emergency, which includes, as I have said, attitude polarization, and other kinds of fragmentation.

If we can practice Dōgen Zenji’s forgetting the self, and attunement to compassion, then perhaps we can think like a planet, think like a virus, think like a ‘we’. There is no end, no utopia, no perfect situation in which humanity can live with all else. There is only attunement to compassion and letting love do what needs to be done. Is this the awareness of the universe waking up in some way to itself? I don’t know. But it implies that we create connections rather than focus on blame, that we pay attention to our own individual actions rather than focusing on calling others to account, that we create communities, and means of communicating with one another, skillfully, rather than wasting energy on anger or hatred which only further inflames and drives polarization and fragmentation. What we can do is little, in one sense: we can focus on our own attitude. We can practice realization. But in another sense, it is much.

“My life amounts to no more than one drop in a limitless ocean. Yet what is any ocean, but a multitude of drops?” (David Mitchell, Cloud Atlas).

If there’s no ‘them’ and ‘us’, how do we deal with conflict and discussion, debate and disagreement? I can offer a couple of suggestions.

First, Jonathan Haidt in his book The Righteous Mind offers some advice on how to approach someone whose ideology and value system is radically different from one’s own: acknowledge it!

Second, the system of Non-Violent Communication (or compassionate communication) offered by Marshall Rosenberg is a system that asks us to consider the needs behind any communication, diffusing the direct confrontation that can come from opposing views.

Third, Lisa Feldman Barrett, author of Seven and a Half Lessons about your Brain suggests creating some ground rules when working with people you disagree with (e.g. follow the data – reread source research and find data that you can agree on; be curious! If you disagree, see if you can avoid defensiveness and look for ways to continue the discussion).

And finally, read Learning to Die by Robert Bringhurst and Jan Zwicky. Zwicky talks about the virtues that the great philosopher Socrates developed in himself to create the equanimity with which he faced his death. Bringhurst urges readers to tune their minds to the wild, to think like an ecosystem, to find consolation in the tiny acts of resilience that the more-than-human world demonstrates. As Alan Watts once said, we may just have to accept that the wild, the universe, is not only bigger, and more long-lasting, but also wiser than we are. Ultimately, it is by confronting and accepting the brevity of our own lives, their tiny insignificance of our individuality, the impermanence of each moment, that we come to understand what matters. Every single act creates a reaction but living with awareness, stepping back, being kind, curious and contemplative, allows love to do what needs to be done through us. Then we realize there is no ‘us’. No ‘them’. Just the practice of realization lets us get out of the way so that we become the way that love does what needs to be done.

Lucy Weir is a philosopher, a writer, and a yogi. She has worked with many challenges, including having an addicted brain and using the revelations that Yoga brings. Lucy’s practice, research, and writing have allowed her to develop both creatively and philosophically. She seeks to facilitate others to achieve their own insights and to practice in a way that enriches action, connects human and more-than-human communities, and deepens inner and outer understanding now. In 2014 Lucy completed a Ph.D. in Philosophy. In 2019 she published Love is Green: compassion as responsibility in the ecological emergency (Vernon Press).

Lucy Weir is a philosopher, a writer, and a yogi. She has worked with many challenges, including having an addicted brain and using the revelations that Yoga brings. Lucy’s practice, research, and writing have allowed her to develop both creatively and philosophically. She seeks to facilitate others to achieve their own insights and to practice in a way that enriches action, connects human and more-than-human communities, and deepens inner and outer understanding now. In 2014 Lucy completed a Ph.D. in Philosophy. In 2019 she published Love is Green: compassion as responsibility in the ecological emergency (Vernon Press).

For more information visit www.knowyogaireland.com

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.