When my eldest daughter was three or four years old, she asked one of those questions that is both innocent and profound, rolled up into one: “Daddy,” she asked without context or provocation, “what have you done to make the world a better place?”

The answer long forgotten in the moment, is still yet taking a lifetime to fulfill. For it’s not simple, like answering why the sky is blue, or eggs, white. The sky is not always blue, nor eggs white, nor life as predictable as our dreams may presume.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us…” –Charles Dickens A Tale of Two Cities

This short abbreviated excerpt from Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities encapsulates the paradox of modern times. A revolution is in the making, and it could come next week, next year, or beyond the next decade. What this revolution may bear is still unwritten, and it is the artist, the baker, the historian, the philosopher, the scientist, and the teacher who will lead the way. The perils of climate change, war, pestilence, intolerance, and hatred prevail, and yet the good of people shines through the smoke of chaos, every now and then, and more often than not.

Still waters prevail in the mind’s eye for someone must tell the stories. From where I stand, much of literature (and photography) presents an eloquent standard of bearing witness, even if only in hyperbole or metaphor. These stories in ceramic and stone, in silver and in pigment, in song and in memory, remain as artifacts of our efforts and of our dreams.

Within this nebula I have felt compelled to bear witness to the fact that more than 1,000 nuclear bombs have been detonated within my Nevada homeland. In 1952, Nevada Governor Charles Russell, showing his ignorance of climax ecology, said, “…we had long ago written off that terrain as wasteland, and today it’s blooming with atoms!” (Quoted in Nuclear Landscapes, 1991).

While I speak for no one but myself, I know many photographers who think of their craft as intimately involved in the evolving relationship between the artist and society – if a fire were to threaten the home, what at first thought does one take when required to evacuate? If an event compels a witness, how often are photographers nearby, even those that may not engage the craft professionally? Cellphones galore, a visual paradise of plenty – everything appears to have frozen fragments preserved in the ether of time.

Humans are engaged in this chaotic narrative, and by our telling, others may be informed, or persuaded to action, or relieved to know that after all, the Earth is still green and blue. The view of the planet from beyond our atmosphere has put a spell on us all, for alone Earth exists, in Darkness. And therein it will remain, unless we add our voices to the growing choir of those who wish to live sustainably, respectfully, without exploiting, without greed, but in a climate of tolerance and peace, clean air and water, with neighbors not enemies, with colleagues, not contrarians.

Perhaps William Shakespeare’s quote sums this up best when he wrote, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves…” [Julius Caesar (I, ii, 140-141)]. We may be victimized but we are not victims; we are capable, we can change, we can adapt, we can persevere. We can show compassion and love, and we can seek beauty and find contentment in their continual renewal. When the world succumbs momentarily to Darkness, the task is to find good earth and plant a tree. A photograph is like a tree in this way.

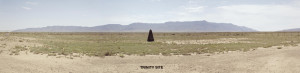

Trinity Site — site of the world’s first nuclear explosion, July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 a.m. Mountain War Time on the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range of the White Sands Proving Ground in the Jornada del Muerto desert, New Mexico. 1988 negatives/2012 panorama print

The poetic language of photography, disguised as plain prosaic fact, intrigues my visual understanding of the places that we define as ‘nature.’ Therein I can bear witness and understand the paradigms that rule our culture and generate the rules that we live by or endure. By creating photographs such as Trinity, I offer testimony to the phenomenal dawn of the nuclear age; at this spot, at this center, in this landscape. Stand at Ground Zero – not any ground zero, and there are now many, but the ground zero. Imagine.

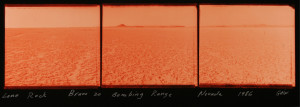

Lone Rock, Bravo 20 Bombing Range, Nevada This triptych explores Bravo 20, a military bombing site, with Lone Rock, center. This site is one of the numerous bombing ranges used by the Fallon Range Training Complex which is located in the high desert of northern Nevada. Lone Rock is within Paiute territorial lands.

Fire, Jepson Prairie Assembled from multiple digital photographs, this panorama of a wildfire in Jepson Prairie, a Nature Conservancy park in northern California, documents the consequences of a carelessly ignited fire that rolled across agricultural fields. This panorama is included in the Peter Goin and Paul F. Starrs California Agriculture Archive at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. 2007 digital negatives/2010 panorama print.

Through this journey from place to place, I can wonder about landscapes through a medium of pigment and paper, of color and tone, of object and space, and light and dark. The fundamental structure of a fort in the wilderness, a preserved prairie distractingly burned, a sacred mountain bombed, a landscape eviscerated. What have we done? Or, to quote Michael Jackson:

…So what you gonna do, what you gonna do? When the new world order come for you. All you can do, what you can do is recognize the truth! Realize these signs could pertain to you too! –What Have We Done? Bone Thugs-N-Harmony featuring Michael Jackson.

Peter Goin, Chair of the Department of Art at the University of Nevada, Reno, and Foundation Professor, is the author of Tracing the Line: A Photographic Survey of the Mexican-American Border (limited edition artist book, 1987), Nuclear Landscapes (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), Stopping Time: A Rephotographic Survey of Lake Tahoe with essays by C. Elizabeth Raymond and Robert E. Blesse (University of New Mexico Press, 1992), and Humanature (University of Texas Press, 1996). He served as editor of a fifth book, Arid Waters: Photographs from the Water in the West Project (University of Nevada Press, 1992). Peter is also co-author of numerous books, including the Atlas of the New West, a collaborative effort with members of the Center of the American West at the University of Colorado at Boulder; A Doubtful River (University of Nevada Press, 2000) a project that examines the complex watershed of the first federal irrigation dam, the Newlands Project; and, Changing Mines in America (Center for American Places distributed by the University of Chicago Press, 2004) reinterpreting the legacy and importance of mining landscapes throughout the United States. In 2005, Peter and Paul F. Starrs served as co-authors of the seminal BLACK ROCK (University of Nevada Press), a dedicated investigation of a phenomenal desert region in northern Nevada.

Peter Goin, Chair of the Department of Art at the University of Nevada, Reno, and Foundation Professor, is the author of Tracing the Line: A Photographic Survey of the Mexican-American Border (limited edition artist book, 1987), Nuclear Landscapes (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), Stopping Time: A Rephotographic Survey of Lake Tahoe with essays by C. Elizabeth Raymond and Robert E. Blesse (University of New Mexico Press, 1992), and Humanature (University of Texas Press, 1996). He served as editor of a fifth book, Arid Waters: Photographs from the Water in the West Project (University of Nevada Press, 1992). Peter is also co-author of numerous books, including the Atlas of the New West, a collaborative effort with members of the Center of the American West at the University of Colorado at Boulder; A Doubtful River (University of Nevada Press, 2000) a project that examines the complex watershed of the first federal irrigation dam, the Newlands Project; and, Changing Mines in America (Center for American Places distributed by the University of Chicago Press, 2004) reinterpreting the legacy and importance of mining landscapes throughout the United States. In 2005, Peter and Paul F. Starrs served as co-authors of the seminal BLACK ROCK (University of Nevada Press), a dedicated investigation of a phenomenal desert region in northern Nevada.

Peter’s photographs have been exhibited in more than fifty museums nationally and internationally, and he is the recipient of two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships. Peter’s video work has earned him an EMMY nomination as well as the Best Experimental Video Award at the 2001 New York International Film & Video Festival. At the turn of the new century, Peter was awarded the Governor’s Millennium Award for Excellence in the Arts.

In fall of 2009, the Black Rock Institute Press published the Fine Art limited edition, slip-cased book titled Nevada Rock Art, Peter’s focused study on Nevada’s petroglyphs and pictographs. Reflecting his long-standing work studying Lake Tahoe, Peter was the author of South Lake Tahoe: Then & Now and co-author with Paul F. Starrs of A Field Guide to California Agriculture that won the J. B. Jackson Prize for publishing excellence (2010).

Information about books is available @ (775) 322-3541 or by fax @ (775) 784-6655. Peter’s web address is petergoin.com. Email is pgoin[at]unr.edu.

This post is part of the newly launched MAHB’s Arts Community space –an open space for MAHB members to share, discuss, and connect with artistic processes and products pushing for change. Please visit the MAHB Arts Community to share and reflect on how art can promote critical changes in behavior and systems. Please contact Erika with any questions or suggestions you have regarding the new space.

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/what-have-we-done/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.