The following essay comes from David J. Wagner, President of David J. Wagner, L.L.C., a traveling museum exhibition production company. Among exhibitions the company has produced is Environmental Impact, which Dr. Wagner personally curated. He is also author of American Wildlife Art.

In March 1871, U.S. Congress appropriated $40,000 for an expedition to the little-known, western region of Yellowstone to be led by Dr. Ferdinand Hayden, director of the U.S. Geological Survey. He invited painter Thomas Moran at the behest of robber baron, Jay Cooke, to document the expedition, along with photographer, William Henry Jackson. Moran had emigrated from England to New York and become chief illustrator for Scribner’s Monthly magazine. On July 21, 1871 the expedition entered the region at the Gardiner River and proceeded up river to what is now called Mammoth Hot Springs. Over a span of 40 days, Moran documented over 30 different locations. His watercolors, which were published in Scribner’s, captured the nation’s imagination. They were also purposefully displayed in the rotunda of the nation’s capital to encourage Congress to pass legislation to establish Yellowstone as our first national park. President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Act creating the nation’s first park on March 1, 1872, with appreciation of nature but not necessarily conservation in mind.

In the same year, Civil War veteran, Edward Kemeys distinguished himself by modeling and installing the first public American wildlife sculpture in the United States. Two Hudson Bay Gray Wolves Quarreling Over the Carcass of a Deer was cast life-size in bronze and installed in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. With it, Kemeys added sculpture as a format, depth as a dimension, and bronze as a medium, to American wildlife art, and he loosened the grip that realism had had on the genre. Kemeys also diversified ecological ideology in art by celebrating the wildness of wolves as predators over thirty years before Jack London wrote and had published, Call of the Wild. Instead of positioning his wolves as predators that should be feared and eradicated, Kemeys celebrated their wildness, though his perspective was not prevalent. Just three years earlier, state legislators in Albany, New York, passed legislation offering bounties to eliminate wolves altogether because of the perceived threat they posed to farmers and society.

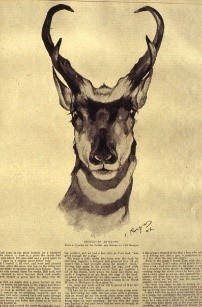

Carl Rungius, a German immigrant who, like Thomas Moran, had come to the U.S. seeking opportunity, was discovered by William Hornaday, the first director of the New York Zoological Society. Hornaday introduced the artist to George B. Grinnell, a fellow member of the Boone and Crockett (hunting) Club. Grinnell, whose epitaph would one day be, Father of The Conservation Movement, was the publisher of Forest and Stream, A Weekly Journal of the Rod and Gun, and he used the magazine to espouse conservation ethics and laws to protect fish and game. Pronghorn Antelope, was the first work by Rungius that Grinnell published. This led to more commissions for Forest and Stream and other magazines, which played a role in the birth of the Conservation Movement. Rungius consequently established himself as a painter and sportsman who appreciated hunting as a means to build character through independence and self-reliance.

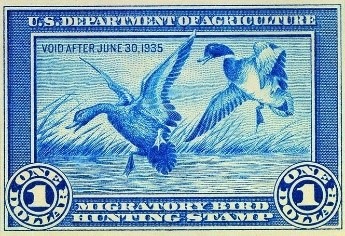

The duck stamp, as the U.S. Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp has become colloquially known, was established in 1934 at the recommendation of a Presidential Commission chaired by J. N. Ding Darling, a Pulitzer Prize winning political cartoonist from Des Moines, Iowa. The Stamp was a form of tax imposed on hunters to fund Game Management, which Aldo Leopold, who authored a book of the same title, defined as: “The art of making the land produce sustained annual crops of wildlife for recreational use.” In its first 50 years, the duck stamp program resulted in the acquisition of over 4 million acres of wetlands, expanded habitat management, and law enforcement. The first Federal Duck stamp features a brush and ink drawing of a hen and drake mallard by Ding Darling.

On March 24, 1989, the Valdez, an oil tanker owned by Exxon Corporation, ran aground on Bligh Reef as it departed after filling up with crude oil from the trans-Alaska pipeline terminal. As much as 38 million gallons leaked into Prince William Sound and eventually impacted some 1,300 miles of shoreline and 11,000 square miles of ocean. As satellites broadcast images of wildlife dead and dying in the oil slick, Swedish-American sculptor, Kent Ullberg, who had just unveiled a monumental sculpture of whopping cranes at the entrance of National Wildlife Federation headquarters in Washington, D.C. to honor “heroic conservation efforts,” was moved through grief to model a somber portrait in clay of a lifeless eagle which he completed in a matter of days. When Mozart’s Requiem aired on the public radio station he was listening to in his studio, a title occurred to Ullberg that captured the pathos of the moment: Requiem for Prince William Sound.

Sculptor Leo Osborne, who lived in Maine at the time, took another approach: “Caulking gun in hand,” he angrily defaced an exquisite Maple Burlwood carving depicting shore birds during their annual springtime mating ritual, and in the process destroyed the beauty and the essence of his art. For Osborne, this destructive act was a personal ‘art happening’ similar to the happenings staged in the 60’s when that form of artistic expression was the rage. Osborne also wrote a poem to accompany his sculpture both of which he titled, Still Not Listening. The title proved to be prophetic twenty years later, when the BP Deepwater Horizon Gulf oil spill eclipsed the Exxon Valdez Spill (April 20, 2010) to become the largest marine oil spill in the history of the world (at an estimated 4.9 million barrels).

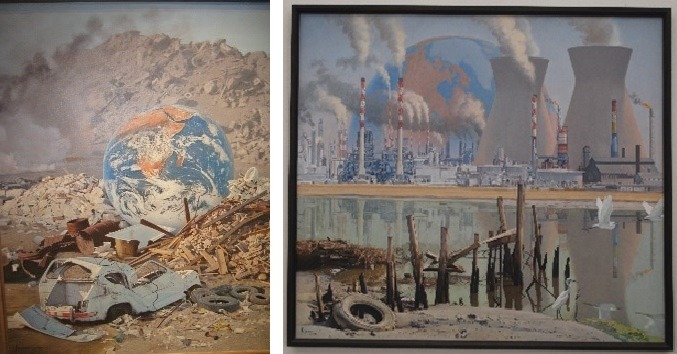

In 1989, Walter Ferguson, a New-York born and American-trained artist (Yale University School of Fine Art; Pratt Art Institute), who had relocated his family to Israel in 1965, created this Environmental activist painting he entitled, Save The World. In 1992, he followed it up with, Apocalypse, picturing oil refineries in the middle ground near the industrial city of Haifa, and the polluted Alexander River in the foreground, which was located just north of Beit Yanai on the Mediterranean where he and his family lived and used to fish before paper-industry, chemical pollution killed off the river.

As if that were not enough for one year, 1989 was punctuated when the U.S. Congress released a report by members of the U.S. Forest Service, the BLM, and Fish and Wildlife prepared over a six-month period, which estimated that only 2,500 pairs of northern spotted owls remained in the Pacific Northwest. At the same time, organizations such as Earth Watch and the Sierra Club estimated that at the prevailing rate of logging, old-growth forests in the Northwest would be depleted within several decades. To protect the owl and therefore its habitat, a battle ensued to have the owl listed by the Department of the Interior as a threatened species under the 1969 Endangered Species Act, which had the potential to shut down logging by bestowing special status on the owl.

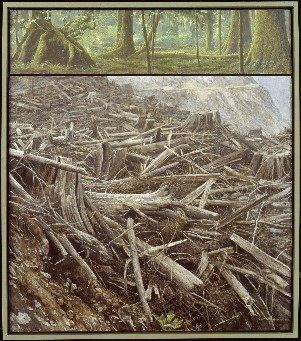

In this context, Canadian painter Robert Bateman created Carmanah Contrasts, the first in what he called his “environmental series.” It had grown out of a collective effort by artists who gathered on Vancouver Island in British Columbia in 1989 to create awareness and resistance against clear cutting of an old-growth area known as Carmanah. Carmanah Contrasts consists of contrasting images in contrasting fields of color layered in meaning. The upper field, which comprises a third of the canvas, is painted in hues of green and contains lush, forest imagery. The lower field, comprising two-thirds of the canvas, is gray and sterile, and littered with hardened stumps and clear-cut debris devoid of life. Ideologically, Carmanah Contrasts is a condemnation of unethical industrial forestry. Aesthetically, Carmanah Contrasts is a pre-postmodern statement by a visionary artist willing to take artistic risks that foreshadowed the next big movement in art.

Bateman followed this up in 1989, with Mossy Branches – Spotted Owl, a painting of the reclusive bird at the center of the battle where logging threatened old-growth forests and where pending legal status threatened livelihoods and a way of life for thousands of loggers and their families. To convey the interdependence of the owl and its habitat, Bateman centered and backlit the owl with raking sunlight and used this compositional device to set off rich mosses which, like the owl itself, rely on the ecology of old growth forests for sustenance. The Northern Spotted Owl was subsequently listed as a Threatened Species on July 23, 1990.

Bateman continued his “environmental” foray with other brave and powerful paintings, notably his 1993 painting, Driftnet, which exposes the grim realities of industrial-scale commercial fishing. For maximum impact, Bateman overlaid the painting with actual non-biodegradable commercial netting that could entangle, cut, and kill unintended victims with ease.

New York artist, Lisa Lebofsky has dedicated a sizeable portion of her young career to painting glaciers, melting ice, and rising seas. This began in 2010, when she was invited by her father, a retired science teacher, to join him along with other science educators, to sail from Argentina for Antarctica. In 2012, pastel artist Zaria Forman reached out to Lebofsky to join an expedition in collaboration with The New Bedford Whaling Museum retracing the 1869 journey of Hudson-River painter, William Bradford along the northwest coast of Greenland. Sermermiut painted in oil on aluminum and measuring 40×64 inches is from that expedition.

In 2014, Lebofsky and Forman traveled to The Maldives (Incoming Surf – Maldives) an island nation with an average elevation of about 5 feet above sea level, making it the most susceptible nation on Earth to the impact of rising sea levels from global warming and melting ice gaps. Lebofsky’s current work is closer to home (Incoming Surf – Montauk) but no less imperiled by the relentless threat of global warming and resulting erosion, in this case, of Long Island’s vulnerable shoreline. There’s also a personal back-story of depression and loss to Incoming Surf – Montauk which humanizes the painting and makes its dark imagery, metaphorically powerful, incredibly menacing, and emblematic as the next paradigm of Environmental Ideology in Art.

Photo Credits (all dimensions listed in inches)

1. The Main Springs at Gardiner River (Yellowstone National Park), 1872, Watercolor, 3×17.63, by Thomas Moran; Source: Unsure, from an old 35 mm slide; Watercolor is probably at The Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, Source: The Athenaeum

2. Hudson Bay Wolves Quarreling Over the Carcass of A Deer, 1872, Bronze, 50x82x58, by Edward Kemeys; Public Domain Source: Wikipedia

3. Pronghorn Antelope, March 1898 Issue of Forest and Stream Magazine, based on a Painting by Carl Rungius

4. First U.S. Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp, 1934, Depicting Mallards by Jay N. “Ding” Darling, Published by The U.S. Department of Agriculture; Public Domain Source: Wikimedia Commons

5. Still Not Listening (Exxon Valdez Oil Spill), 1989, Maple Burlwood and Vinyl Caulking, 21x24x8, by Leo Osborne; Permission: by Leo Osborne

6. Requiem (Maquette for Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Monument in Valdez, AK), 1989, Bronze, 26.5x8x8, by Kent Ullberg; Permission: Kent Ullberg

7. Save the Earth, 1989, Oil on Canvas, 47.75×37.75, by Walter W. Ferguson; Permission: Michael Ferguson, Photo: Stauth Memorial Museum

8. Apocalypse, 1992, Oil on Canvas, 43×51, by Walter W. Ferguson; Permission: Michael Ferguson

9. Carmanah Contrasts (Vancouver Island, British Columbia), 1989, Acrylic on Canvas, 40×45, by Robert Bateman; Permission: Birgit and Robert Bateman

10. Mossy Branches – Spotted Owl, 1989 Acrylic, 16×20, by Robert Bateman; Permission: Birgit and Robert Bateman

11. Driftnet (Pacific White-sided Dolphin & Lysan Albatross), 1993, Acrylic on Canvas, 36×36, by Robert Bateman; Permission: Birgit and Robert Bateman

12. View from Sermermiut (Greenland), 2013, Oil on Aluminum, 40×64, by Lisa Lebofsky; Permission: Lisa Lebofsky

13. Incoming Surf – Maldives, 2015, Oil on Aluminum, 25×40, by Lisa Lebofsky; Permission: Lisa Lebofsky

14. Incoming Surf – Montauk (Long Island, NY), 2015, Oil on Aluminum, 40×42, by Lisa Lebofsky; Permission: Lisa Lebofsky

2016 © David J. Wagner

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.