Author(s): Michael Charles Tobias, Jane Gray Morrison

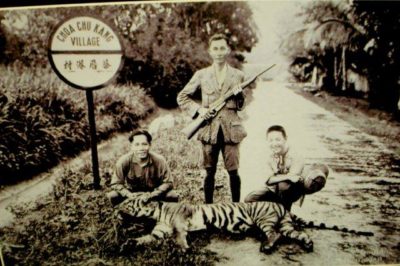

Throughout much of our lives, we have tried to rescue animals still breathing from their fetid cages; and from the indifferent, usually impoverished human captors, in open animal markets from the West African capital of Mali, Bamako, to roadsides in Kenya, animal hells in Central India, northern Russia, western Saudi Arabia, across Yemen and Indonesia, to remote villages in China. The syndrome of animal cruelty and animal consumption has systematically gotten our species to its current zoonotic crisis, covid-19 (SARS-CoV-2).

A brief prelude to the 2020 pandemic: Romans, particularly those who sought to show off their wealth or power, exercised maniacal cruelty to animals. This was carried out every day, for centuries, whether by animals being slaughtered for food, chained in captivity, relentlessly pursued by veritable phalanxes of mercenary sport hunters, being killed and buried with humans as a petition to the gods (e.g., mass animal sacrifice, a practice borrowed from two-thousand years of Egyptian tradition), and the constant show of force, so called, by one insecure Emperor after another glorifying in the public massacre of thousands of animals, typically imported from North Africa (e.g., lions, elephants, giraffe).1 Roman diets included everything from dormice to ostrich.2

This Western grotesque relationship with Others is the most seminal through- story in our history. It touches every aspect of our past, and our present. Great inflection points can be highlighted – like the dietary, human demographic and economic shifts accompanying the Crusades, the Black Plague, or The Hundred Years War. But the out-of-control killing of animals never ceased, despite human, historic fluctuations in everyday life and death.

According to food history consultant, Dr. Annie Gray, “the range of animals and birds consumed in Georgian Britain was astounding – nothing that moved was safe from the cooking pot.” From beavers to the hedgehog, all was fair game. In addition, there was “extravagant medieval culinary diversion: fantastic beasts” including “the cockentrice” which “comprised half a pig sewn to half of a capon (a castrated and fattened chicken).”3

Japanese have long had a dietary tradition of Ikizukuri, meaning prepared alive and, in the case of octopus, still moving on the plate as the diner consumes it. The varieties of torture meted out to marine invertebrates and vertebrates, to frogs, snakes, enchinoderms like sea-urchins, decapod crustaceans (shrimp and prawns) and to insects, including the live larva of numerous grubs, continues unabated throughout the world.4

Which brings us to the current situation with “wet markets”. National Public Radio journalist Jason Beaubien has recently reported on the Tai Po wet market in Hong Kong, writing, “Live fish in open tubs splash water all over the floor. The countertops of the stalls are red with blood as fish are gutted and filleted right in front of the customer’s eyes. Live turtles and crustaceans climb over each other in boxes. Melting ice adds to the slush on the floor. There’s lots of water, blood, fish scales, and chicken guts.” The market also sells “Himalayan palm civets, raccoon dogs, wild boars and cobras.”5 The reality of such wet markets has erupted in the consciousness of those who have been even remotely following the covid-19 pandemic. For example, noted animal rights philosophers Peter Singer and Paola Cavalieri have written, “At China’s wet markets, many different animals are sold and killed to be eaten: wolf cubs, snakes, turtles, guinea pigs, rats, otters, badgers, and civets. Similar markets exist in many Asian countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines.”6 Zoologist Juliet Gellatley declares, with reference to the Wuhan live-animal market, “Over 100 different animals are sold here, including wolf pups, civet cats, poultry and snakes.” And she continues, “These animals are kept in cramped, dirty conditions, with direct contact with humans. These markets are referred to as ‘wet markets’ – so called because animals are often slaughtered directly in front of customers.”7

The live-customer aspect is no surprise in the United States, where buyers and sellers of “livestock” (live being the operative sales pitch on both sides of the eventual fork and knife) have been meeting for hundreds of years to transact their merciless exchanges. Which is why, for example, a study of increased potential for transmission of “swine-origin IAVs” [Influenza A viruses] at open live animal markets was conducted in just one of those symptomatic open-market transactional states: Minnesota, by researchers in 2015.8

From the mid-Western United States to nearly every other continent, there is plentiful data (though severely under-documented or tallied) to make clear that “unregulated and usually filthy markets are found all over Asia and Africa,” for example.9

During the first two weeks of February, 2020, Chinese police raided homes across China and arrested over 700 people “for breaking the temporary ban on catching, selling or eating wild animals.” Among the “40,000 animals” taken during the crackdown, “squirrels, weasels and boars.” But this did not begin to account for the countless snakes in jars, or those merchants who were legally able to sell “donkey, dog, deer, crocodile and other meat.” And, as a retired zoologist from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wang Song, declared, “In many people’s eyes, animals are living for man, not sharing the earth with man.”10

But whether thousands of years of Chinese cultural traditions will be irrevocably altered by one outbreak appears unlikely. Although on February 24th, 2020, the 16th Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 13th National People’s Congress, put into effect an edict “Comprehensively Prohibiting the Illegal Trade of Wild Animals, Eliminating the Bad Habits of Wild Animal Consumption, and Protecting the Health and Safety of the People.” Time will tell.11 On April 2nd, 2020, Chinese authorities ordered a ban -to take effect one month later- on the eating of dogs and cats in at least one city, Shenzhen. But across the vast reaches of China, at least 10 million other dogs and 4 million cats are likely to be slaughtered in 2020, often boiled alive. At the same time, the grim torture of bears kept alive to perpetually drain them of their bile for its supposedly medicinal ingredient, ursodeoxycholic acid12 (like kept lambs for veal chops, geese or ducks for Foie gras, an endless litany of other tortures) continues.

In a discussion with Dr. Peter J. Li, an Associate Professor of East Asian Politics at the University of Houston-Downtown, and China Policy Specialist of Humane Society International, back in late 2012, he described how the 1988 Wildlife Protection Law, China’s most comprehensive such set of mandates, was severely flawed in that it positioned “wildlife animals as ‘natural resources’ to be used for human benefits. Local authorities and businesses have, however, chosen to use the WPL as their bible to justify their business operations of wildlife exploitation.”13

Aside from the sheer horror such practices evince in many people, it is statistically unlikely that the majority of humanity – which continues its practices of meat and fish consumption – would find these dietary standards at all reprehensible, excepting those ethicists and other activists who write such papers as, “The Moral Standing Of Insects And The Ethics Of Extinction” by Jeffrey A. Lockwood. In this important essay of 1987 he posited that “The criterion of sentience which includes concepts of pain, consciousness, thought, and awareness appears to provide an intuitively satisfying, empirically approachable, philosophical basis for including a being in our moral considerations. Existing evidence indicates that insects qualify as sentient and their lives ought to be included in moral deliberations.…” [and] “if there is a conflict in which all other interests are equal, an entity with even infinitesimal moral significance may determine the right course of action.”14

Nearly 35 years ago, when Lockwood wrote this, it was in the midst of an intense wave in animal behavior, biomedical ethics and general philosophical and biological discussion focusing upon animal rights that encompassed such writers – all cited by Lockwood – as S.R.L. Clark, The Moral Status of Animals (1977), D. R. Griffin, The Question of Animal Awareness (1976), A. Jolly, A New Science That Sees Animals As Conscious Beings (1985), J. Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1971), T. Regan, The Case For Animal Rights (1983) and P. Singer, Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for our Treatment of Animals (1975). But in spite of the vast number of insects and spiders destroyed during the Green Revolution, with its global celebration of chemical adulterants15 there was little attention paid to big moral questions as applied to the smallest among us. To find such serious and breathtaking deliberations, one would have to look back to the Jain and Buddhist annals, to Mahavira (ca. 497-425 B.C.E.) and his disciples most notably.16

And today, insects and spiders are going extinct in multitudes – whole populations disappearing in a day, a consequence of human behavior that, at least with such apex pollinators as bees, many are hearing the clarion call. Whereas an appreciation of the eco-dynamics occurring amongst bacteria and viruses is far more esoteric, for the majority of us. Until our bodies suddenly tell us that something has gone terribly awry. And as we now collectively engage in “war” against the latest disease calamity in nearly every human community, the many revelations concerning zoonoses has not yet fully entered the ethicist’s lexicon, perhaps because the contemplation of saving mosquitoes or cockroaches, locust or fleas is unlikely to ever gain an equal footing with humans, as long as we remain the dominant vertebrate species on Earth. Dr. Paul Ehrlich and I discussed this, in various guises, with respect to Lepidoptera (the nearly 180,000 known species of butterflies and moths of which Paul is one of the world’s leading authorities) in our book Hope On Earth: A Conversation.17

But when a mosquito or cockroach should suddenly be seen to hold the power, for example, of a new wonder drug, or, better still, antibody and eventual vaccine, we are likely to see a philosophical revolution, that will either work to change hearts and minds, or fail to do so. Addressing the combination of horseshoe bats and Chinese pangolins together possibly infecting humans at a live animal market in Wuhan, China, Johnathan Epstein, the epidemiologist/veterinarian involved in tracking down the animal source of the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) virus from civet cats in animal markets in Guangdong, China in 2003, has stated that “…about half of all known human pathogens are zoonotic, which means they originated in animals.”18

In the last century, at least 70 major infectious disease outbreaks and/or continuing, animal-transmitted diseases have tortured all those hundreds-of-millions of victims concerned, in a systemic, combinatorial mayhem that remains fundamentally an ecological result of human ignorance, indifference, cruelty, and trespass. Some of those diseases, and the implicated species disrupted, like the current “beast,” as the covid-19 viral species has been named by numerous first responders, includes: Anthrax-numerous farm animal species; Bubonic plague-dozens of mammalian taxa from camels and goats to sheep and rabbits; Chagas disease-armadillos; new variant Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, in humans, “mad cow disease”-bovines; Ebola virus-other primates; Giardiasis, Rabies and Influenza, dozens of wild and semi-wild mammals; Lyme disease-the deer/tick matrix; MERS coronavirus-camels, bats; Rickettsia-canids and rodents; Zika virus-numerous other primates.19

In every instance, it would be too simple and incomplete a mental sequence of events to suggest that these are Gaia’s (the Earth’s) antibodies to human over-population. For one, the plague (“Black Death”) – humanity’s worst pandemic thus far, peaking throughout Europe and Eurasia between 1347-1351 – wiped out between 30% and 60% of the afflicted regions’ populations, or as many as 200 million people.20 But by the time William Shakespeare was born (1564) the human population had made a total comeback, plus some. The underlying story fueling every zoonotic eruption has been the same: human’s encroaching on wild habitat, capturing, poaching, consuming or transporting other species; commingling in usually unsuspecting ways with a wild animals’ urine or feces, or the fleas and diseases it may be carrying. Unnatural intrusiveness, in other words.

With the human species on a single-minded path towards 9.5, 10, 11 or even 12 billion individuals, depending upon which predictive model one cares to believe in, there is little if any persuasive empirical evidence, thus far, to suggest demographic amelioration. Indeed, our continuing population explosion (80 million humans added to the planet each year), and that magnitude of human biomass in proportion to the fast-waning portion of all other wildlife on the planet, is a ratio painfully out of balance, with no promise for improvement.

Many have objected to the notion of Covid-19 being named by the U. S. Administration as “the Chinese virus,” calling out such bellicose epithets as ignorant, unhelpful, deliberately war-like and profoundly racist. Yet, at the same time, it is difficult not to forget what Dr. Li told us in our “Animal Rights In China” conversation for Forbes over seven years ago: “Never in its 5,000-year history did China ever raise and keep hundreds of millions of wildlife species in captivity as it is today.” But, he added, “Today, Chinese consumers, according to a recent report eat twice as much meat as those in the United States. This is not surprising. China surpassed the US as the world’s biggest meat producer in 1990, and the Chinese authorities have long looked to the industrialized West as the object of emulation in meat production. While Westerners greet each other by asking ‘how are you,’ Chinese people traditionally greeted each other by saying ‘Have you eaten?’”21

And as Dr. Li explained, this may culturally relate to the legacy amplified during the ascendancy of Mao. Said Dr. Li, “Many Chinese mainlanders (I am using this word to distinguish Chinese on the mainland from those in Taiwan and Hong Kong) are, in my opinion, possibly indifferent or insensitive to animal suffering (to varying degrees). But let me also state for the record that, again in my opinion, they themselves are not to blame. Neither is Chinese traditional culture to blame. People become indifferent or insensitive perhaps because they have been socialized to be so, particularly under Mao, when sympathy for the downtrodden, love of pets, wearing make-up, and displaying individual taste in fashion were all condemned as bourgeois and rebellious.”22

We posed to Dr. Li, “So across China, at the local level, it’s a political quagmire guaranteed to perpetuate animal suffering?” His answer was politically complicated, but, in our view, implied a version of business as usual all too familiar in the West.

That Western experience of cruelty – both inside and outside of pandemics – has been well illustrated by Frank M. Snowden in his book Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present.23

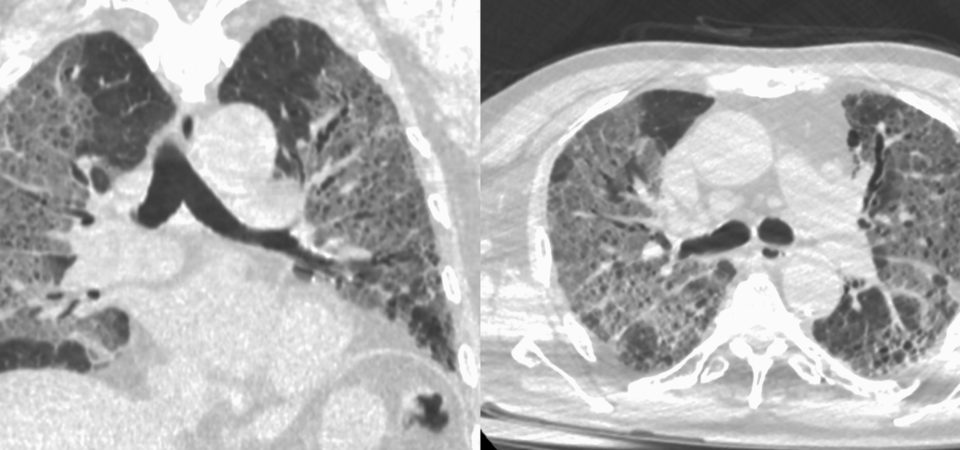

But now, the stakes have changed at a level not seen since the Spanish (Haskell County, Kansas) Influenza Pandemic of 1918 caused by the H1N1 virus, of avian genetic origin,24 while researchers currently search for another “1.67 million unknown [but projected] viruses infecting the animals of Earth”.25 Moreover, we have every reason to fear transmission to other mammalian species, the first being the tigers in the Bronx Zoo. In addition, the most critical endangered primates in the wild are at tremendous risk, particularly mountain gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans and bonobos. We don’t know what other mammalian pulmonary vulnerabilities exist out there.

But it would appear all but certain that at the heart of this global human tragedy is a singular, ecological verity: the likely vortex of this epidemic, and more to follow, is humanity’s most sincerely ill-advised obsession with killing other animals and eating them. That includes the nearly 3 trillion estimated terrestrial and marine vertebrates and invertebrates (eg., from cows to lobsters; from turkeys to fish) that humans wantonly slaughter annually.26

Tobias and Morrison oversee the Dancing Star Foundation -www.dancingstarfoundation.org

This essay will- with some updated information -be part of their forthcoming book, On the Nature of Ecological Paradox, from Springer Nature Publishers, New York

Special Thanks to Dr. Paul Ehrlich and Dr. Eric Hoffman

Footnotes:

- See Dr. Iain Ferris’ Cave Canem: Animals and Roman Society, Amberley Publishing, Gloucestershire, UK 2018.

- See “Dormice, ostrich meat and fresh fish: the surprising foods eaten in ancient Rome,” by Erica Rowan, HistoryExtra, BBC History Magazine, March 19, 2015, https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/dormice-ostrich-meat-and-fresh-fish-the-surprising-foods-eaten-in-ancient-rome/

- “Pig-chickens, beavers’ tails and turtle soup: 8 weird foods through history,” Dr. Annie Gray, HistoryExtra, BBC History Magazine, August 27, 2015, https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/pig-chickens-beavers-tails-and-turtle-soup-8-weird-foods-through-history/

- See “11 Foods Eaten Alive That May Shock You,” by Brent Furdyk, Food Network, October 19, 2017, https://www.foodnetwork.ca/fun-with-food/photos/foods-eaten-alive-that-may-shock-you/#!irish-garlic-oysters; See also, “It’s time to ban eating live creatures on I’m A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here,” by Alice Wright, METRO, November 22, 2017, https://metro.co.uk/2017/11/22/its-time-to-ban-eating-live-creatures-on-im-a-celebrity-get-me-out-of-here-7080860/; and “10 Animals That People Eat Alive,” by Simon Griffin, ListVerse, June 21, 2018, https://listverse.com/2013/03/06/10-animals-that-people-eat-alive/Accessed April 1, 2020; and “Anthony Bourdain took people on a journey of the world – often by eating really strange things,” by Michael Collett, ABC News, Australian Broadcasting, June 9, 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-09/anthony-bourdain-weird-things-hes-eaten/9852966, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- “Why They’re Called ‘Wet Markets’ – And What Health Risks They Might Pose,” Jason Beaubien, January 31, 2020, NPR, https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/01/31/800975655/why-theyre-called-wet-markets-and-what-health-risks-they-might-pose

- “The Two Dark Sides of COVID-19,” Peter Singer, Paola Cavalieri, March 2, 2020, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/wet-markets-breeding-ground-for-new-coronavirus-by-peter-singer-and-paola-cavalieri-2020-03

- “Eating Animals Will Be the Death of Us,” by Juliet Gellatley, February 4, 2020, The Ecologist, Common Dreams, https://www.commondreams.org/views/2020/02/04/eating-animals-will-be-death-us, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- “Live Animal Markets in Minnesota: A Potential Source for Emergence of Novel Influenza A Viruses and Interspecies Transmission,” by Mary J. Choi, Montserrat Torremorell, Jeff B. Bender, Kirk Smith, David Boxrud, et.al., Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 61, Issue 9, 1 November 2015, pp. 1355-1362, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ618, https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/61/9/1355/432409

- See “Inside the horrific, inhumane animal markets behind pandemics like coronavirus,” by Paula Froelich, The New York Post, MarketWatch, January 25, 2020, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/inside-the-horrific-inhumane-animal-markets-behind-pandemics-like-coronavirus-2020-01-25

- “‘Animals life for man’: China’s appetite for wildlife likely to survive virus,”

by Farah Master and Sophie Yu, Reuters, World News, February 16, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-wildlife-idUSKBN20A0RK - See WCSNewsroom, “WCS Statement and Analysis: On the Chinese Government’s Decision Prohibiting Some Trade and Consumption of Wild Animals,” WCS News Release, New York, February 26, 2020, https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/13855/WCS-Statement-and-Analysis-On-the-Chinese-Governments-Decision-Prohibiting-Some-Trade-and-Consumption-of-Wild-Animals.aspx

- See BBC NEWS, “Shenzhen becomes first Chinese city to ban eating cats and dogs,” 2 April 2020, n.a., https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-52131940, Accessed April 2, 2020.

- See “Animal Rights in China,” by M.C. Tobias and J. G. Morrison, Forbes, November 2, 2012.

- Florida Entomologist 70(1), March 1987, pp. 70, 73. https://journals.flvc.org/flaent/article/view/58243/55922, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- See, for example, “The Toxic Consequences of the Green Revolution,” by Daniel Pepper, US New and World Report, July 7, 2008, https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2008/07/07/the-toxic-consequences-of-the-green-revolution; See also the vast scientific commentary on the writings of Rachel Carson, https://www.rachelcarson.org/Bio.aspx

- See Life Force: The World of Jainism, by M. C. Tobias, Asian Humanities Press, Fremont, California 1991.

- University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill., 2014. See also, John L. Capinera, “Butterflies and moths”. Encyclopedia of Entomology. 4 (2nd ed.). Springer, New York, 2008, pp. 626–672.

- See “’This is not the bat’s fault’: A disease expert explains where the coronavirus likely comes from,” By Brian Resnick, February 12, 2020, VOX, https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2020/2/12/21133560/coronavirus-china-bats-pangolin-zoonotic-disease, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- World Health Organization, “Zoonoses,” https://www.who.int/zoonoses/en/Accessed April 1, 2020. For one prime example, see the PBS feature film documentary, “Mad Cowboy,” the story of Montana rancher turned vegan, Howard Lyman, http://www.dancingstarfoundation.org/mad_cowboy.php; According to an NIH study, “Prioritizing Zoonoses for Global Health Capacity Building – Themes from One Health Zoonotic Disease Workshops in 7 Countries, 2014-2016,” by Stephanie J. Salyer, Rachel Silver and Casey Barton Behravesh, “An estimated 60% of known infectious diseases and up to 75% of new or emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin.” Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Dec; 23(Suppl 1); S55-S64. Doi: 10.3201/eid2313.170418, PMCID: PMC5711306, PMID: 29155664, Cent3ers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. That data comes from Woolhouse ME, Gowtage-Sequeria S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005; 11:1842-7, 10.3201/eid1112.0500997; and Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008; 451;990-3.10.1038/nature06536

- “Historical Estimates of World Population,” United States Census, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/international-programs/historical-est-worldpop.html

- See https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeltobias/2012/11/02/animal-rights-in-china/#4f70ddb17d57; See also, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/9605048/China-now-eats-twice-as-much-meat-as-the-United-States.html, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Op.cit., “Animal Rights In China,” M.C.Tobias and J. G. Morrison, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeltobias/2012/11/02/animal-rights-in-china/#4f70ddb17d57, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, 2019. See also the interview in The New Yorker between Snowden and Isaac Chotiner, “How Pandemics Change History,” March 3, 2020.https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/how-pandemics-change-history, Accessed April 5, 2020.

- See “History of 1918 Flu Pandemic,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-commemoration/1918-pandemic-history.htm, Accessed April 1, 2020. For possible Kansas origins, see Kansas Historical Society, https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/flu-epidemic-of-1918/17805, Accessed April 1, 2020.

- See “Why Scientists Are Rushing to Hunt Down 1.7 Million Unknown Viruses,” by Brandon Specktor, LiveScience, February 23, 2018, https://www.livescience.com/61848-scientists-hunt-unknown-viruses.html.

- See also data for overall human consumption of animals world wide in the book,God’s Country: The New Zealand Factor, by M. C. Tobias and J. G. Morrison, A Dancing Star Foundation Book, Zorba Press, Ithaca NY, 2011.

(C) 2020 by Dr. Michael Charles Tobias and Jane Gray Morrison

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.