Author(s): Professor William Davis

Artist Bill Davis has worked on 6 continents. His project, No Dark in Sight, is funded to exhibit how artificial light is used to manage culture– as a dystopian condition rewriting our unfit relationship to darkness. Aware of our Anthropocene era, Davis exhibits empirical inquiry, sustainability, and human impact. Like artists before, he uses environmental science to express his humanity. Davinci relied on math, Michelangelo performed autopsies, and Turrell engineered temples for light. Trained to embrace light, Davis is not opposed to its artificial form, just focused on its counter-evolutionary connection to the biosphere. He now calls light a frenemy. When night looks like day, we have a problem. It’s unnatural. Davis photographs many sites meeting Bortle Dark-Sky scale ratings as recklessly over-lit nighttime space. Look no further than cities to find the unnatural light that redefines their night. No Dark in Sight essentially observes light trespass. Quality of light affects quality of life. Davis awakens us to darkness as a sovereign right because we are not alert to its absence as a corporeal threat. No Dark in Sight invites viewers to meditate on their relationship to light– as consumers and producers.

Oil and Water,

Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA

“Oil and Water” shows a frozen pile of black and white sludge. (See lecture: 9:30). Not unlike a crime scene, it was hard to stomach. This bright peak cut a path of crystalized frost into the night sky above the parking lot it occupied– splitting the composition crosswise. The massive slope of the day’s leftovers towered over cars like Yosemite’s Half Dome over its valleys. Photographer William Henry Jackson’s 19th century spirit was afoot. I set my tripod on the frozen asphalt and waited for someone or something to confess to this transgression against humanity. No one came forward. Sadly, I knew I was the judge, the victim, and the culprit.

Human nature is staged against human hubris in “Oil and Water”. The two don’t mix. One is lifegiving; the other not. No two substances have a greater grip on our planet. One we desire, one we need. This image unfolds a disquieting scene of mixed sludge, which conflates compounds we need with those we don’t. We kill for both. If water is justice, fossil fuel is a crime. Less natural is the new normal.

Swarm

Portage, Michigan, USA

“Swarm” is a hyperactive image, which conveys the nature of supply and demand. A close study illustrates the complicated relationship between natural and unnatural worlds– more specifically in this image, moths dazed by artificial light. (See lecture: 14:15). As an indicator species for the state of biodiversity, moths are a key “supply-side” ingredient to the “demand-side” nutritional needs of bats, spiders, lizards, and birds. I witnessed frenetic moths dazed in a path created by artificial light used for an American flag. As I photographed this swarm, it looked like the violent and expressively painted canvases of Pollock and DeKooning. The light assaulted my eyes but more greatly assaulted the confused moths. I was immersed in a grotesque site– questioning light and its relationship to life.

Abstract Expressionism confronts us in ways that challenge the preconceived or pedestrian definitions of art. It alienates us from reason, immerses us in chaos, and makes the natural world unclear. Much like watching insects negotiate for space in flag lighting.

This image analogizes a culture’s desire to prioritize self-service over self-preservation– like a selfish canary painted into an abstract coal mine.

Canvas of Light

Madrid, Spain

“Canvas of Light” surprises and disappoints. It reminds us that photography is a time capsule– made to convey the lived human experience. All photographs remind us to remember. The uplighting in this photo reminds me to recall the paintings of Diego Velasquez. It could have been a detail from Las Meninas or The Education of the Virgin. Velasquez embodied the Golden Age, which promoted empathy, equality, inquiry, and human dignity. I positioned my tripod behind Madrid’s Prado Museum where Velasquez paintings hung– hypnotized by lit canvas hanging from the roof. Standing at the heel of the museum that embraces the Golden Age, this canvas appeared assaulted by light and engulfed in flame. As if light below had demonized the cloth. Is the night sky not pillaged in the same way– with the afterglow of artificial light tarnishing a once more natural and golden age?

Following sunset I toured Madrid, Europe’s reputed brightest city at night– to discover how that reputation was earned. (See lecture: 36:10). I was excited to start my tour at The Prado; and later deflated to sink in the undertow of its artificial light. As gatekeeper to art, culture and the legacy of a gold-tinged era, The Prado had over-lit the community it purportedly served.

Unreal Estate

Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA

“Unreal Estate” unnervingly depicts a mall being constructed to over-accommodate a Middle American community’s consumer desire. (See lecture: 8:35).

I looked through the autumn chill– stunned to watch sky swallow earth. This image prompts me to recall the mythology in Goya’s Saturn in which the god of time grotesquely devours his son. Yet “Unreal Estate” advances that metaphor– as if the night sky, unable to avoid its own trajectory, becomes the last cannibal standing– eating the buildings and itself. In trying to prevent his fateful doom, Saturn only made his longevity and legacies less sustainable. In trying to prevent the night from occurring, we only make the future for the natural world less secure and stable. In this modern telling, the mall structures are constructed of the same building blocks and composed in similar form– with one sprung from the other like a vulnerable son from a dominant father. I stood witness to a volatile and electric blanket of jaundiced orange skyglow envelop this family of cinder block and the immediate troposphere.

Can we summon the will to compose a better self-portrait? If not, the autopsy of our planet will reveal the myth of a sole cannibal with nothing left to eat but itself.

Free Light

Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

“Free Light” is an abbreviated title for America’s most disturbing and inhumane chapter. What started as an interest to photograph a lit Ferris wheel became a greater discovery. Behind the spinning disc was a remarkably illuminated reflection of 100,000 northerly lights dancing across the facade of The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. The glass seemed to melt the light. It was like seeing two Ferris wheels simultaneously: one imagined, the other real. (See lecture: 23:41).

Yet spinning wheels of light became secondary to the primary message staring me down– this site honors the legacy of free will; and it was like watching shooting stars. After I made the image, I paused to consider what the North Star meant to the 100,000 slaves who secured their freedom (and what light trespass may have done to imperil their journey). Light pollution, therefore, is more than a threat to public health and safety. It could be discussed as a near dismantling of free will– skewed by a few decades between the end of the railroad and beginning of artificial light. Be it not for a century of dark nights, freedom tells a different story.

Viva dark skies!

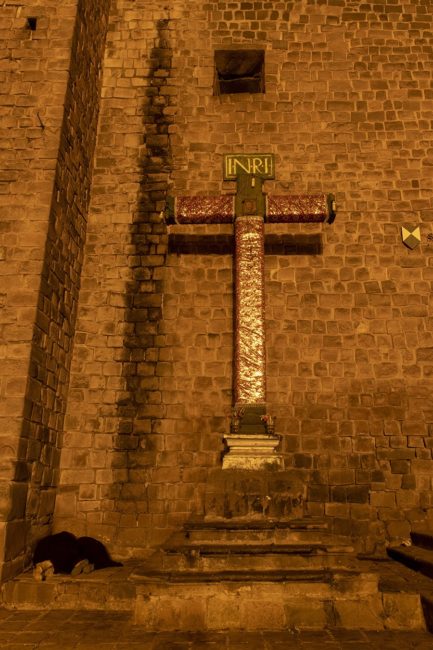

Sacred Light

Cusco, Peru

“Sacred Light” illustrates the multiple meanings of sacred sites. A place for worship is also one for refuge; yet the area is bathed in second-hand light, like billowing smoke cast from a nearby thurible. I traversed Cusco’s Wajaypata to scout sacred sites. This meant exposure to the cross and its symbolism. Like McDonald’s arches, the cross occupied a space between museums and cathedrals.

“Sacred Light” prompts me to reflect on Christian artist Andre Serrano’s Piss Christ. He made the work to convey the conflict between commerce and Christianity, which was visibly evident in Peru. Cusco’s Catholic Church collects rent from Starbucks, KFC, and McDonalds. In this image I see mortality, disenfranchisement, power, faith, and despair. The yellow orange light cast by nearby merchants bathed the space in a ureativ glow. I was as astonished to find trespassing light that flushed Peruvians in a toxic haze.

A wrapped, once bare, cross towers above the huddled figures in vertical domination. I bowed my head in disbelief. The prayer position that would otherwise seem so clearly appropriate had lost all agency when I stood at the foot of an impotent symbol– bigger than but not in service of those asleep below.

Safe Space

Cincinnati, Ohio Zoo, USA

The exhibit in this photo is designed to protect captive wildlife. However, there were no signs of activity in this barren, azure blue, and ominous “Safe Space”. Had its inhabitants been scared away by the red Exit sign or the hovering tungsten eye so reminiscent of Redon’s Cyclops? The dreamy enclosure echoed the surrealism of Tanguy, the solitude of Dali, and color fields of Rothko. Veins on fake trees looked like vascular hands on melting clocks. I could barely see my own reflection on the glass of the nocturnal house that separated me from the captive lives.

I think of unsafe spaces when seeking safe ones. This image conveys that need for safe spaces because of the hostile instability existing outside of them. Nocturnes can surely value that condition. Is naturally dark night sky not an endangered species? Is the biosphere not made unsafe by the light we produce? Can we find compromise?

Redon and Dali remind us that sleep fuels creativity. We depend on one to provide the other. Deep natural darkness, like secure safe space, is hard to find. This manufactured site was dreamlike, but its mere existence demonstrated the nightmares at play in our ecosystem.

What positive role does light play in our experience as human beings and how have we evolved to depend on light, sustainable or not? Hear more about Bill’s experience creating this art by listening to his No Dark In Sight lecture given at Western Michigan University.

The sharply focused, glimmering surfaces of Bill Davis’s work illuminate the pervasiveness of light pollution in acute and subtle ways. Imbued with a restrained sense of solitude, the photographs of Bill Davis, Associate Professor and Area Co-Coordinator of Photography and Intermedia at Western Michigan’s University’s Gwen Frostic School of Art, summon the subliminal, addicting pulse of an iPhone’s lonely blue glow, the constant glare of our contemporary world’s highly commercialized light show, as well as the loss we barely know to grieve—the near complete lack of seeing stars in the sky, even in many rural areas. Each highly reliant on the visual, the fields of science and art have long been bedfellows, and Bill Davis’ work speaks to that deeply-woven interrelationship. As his recent exhibition, No Dark in Sight / Light and the Night it Transforms, at the Western Michigan University’s Richmond Center for Visual Arts came to a close, Bill and I corresponded about his photographic shoots in Kalamazoo, Michigan; Las Vegas, Nevada; and various locations in Peru, including Machu Pichu among other sites.

Full interview to be uploaded soon.

Listen to Bill Davis talk about his work in Madrid, Spain | Ray Del Rey Interview

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.