Can’t you draw something beautiful? I do get that sometimes.

No, I won’t argue that crocodilians are beautiful, at least not in the sense of most standards of beauty in the Western world. But they are amazing animals. And they are cool, in that predatory, reptilian way. I say that as a fan who has appreciated dinosaur-like critters since my early childhood. Like most young boys, I loved dinosaurs. I had a set of plastic ones that I got from my grandfather on my sixth birthday. As I grew a little older, I discovered that there were living dinosaurs or at least relatives, still around. It was my imagination filled with dinosaurian monsters that initially latched onto crocodilians. The visible teeth, a suit of scaly armor, their reptilian predatory stare, were all aspects that fired my inner dinosaur. Initially, they played the role of a predatory monster in my mind, watching old Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan movies where dozens of big Nile Crocs would slide menacingly into the water as the boats went by. There was the inevitable fight between Tarzan, armed with a knife, and a huge rubber alligator. Crocodiles and alligators were thrilling.

My interest in reptiles broadened and deepened as I grew older, and I came to realize that crocodilians were much more than dinosaurian killing machines. They had complex lives, they cared for their young, and were much more intelligent than most people knew. In the places where they live, they are apex predators and play an important role in the survival of many other species. And, the crocodilians we have now are a mere shadow of what they had been in the distant past. They were much more diverse 100’s of millions of years ago. There were vegetarian crocs, species that had long legs and lived on land, and enormous crocodiles that preyed on dinosaurs. A few types survived the great extinction event that finished off the dinosaurs, and are now the last ambassadors of the great Mesozoic reptiles. Today, there are 25 living species recognized by taxonomists.

By the 1960’s crocodilians were facing another extinction crisis, this time from humans, not extraterrestrial falling rocks. The fashion industry’s demands for skins took the biggest toll, and there was human encroachment into crocodilian habitats. The pressure on wild populations became intense, as it became a way to extract cash from resources that were easily available to poor people living near crocodile habitats. Wild populations plummeted around the world.

In 1973 the American Alligator, on the verge of extinction, became protected by the Endangered Species Act. They made a dramatic comeback, and in 1987 were declared completely recovered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Alligator farms and controlled hunting now supply the fashion industry, and the alligator thrives in the wild. Similar changes happened elsewhere in the world, with crocodile farms supplying superior quality leather to skins taken from wild crocodiles.

In addition to the value of their skin, crocodiles and humans compete for living space. Humans are generally not very tolerant of large predators in their neighborhoods. A couple of species are notorious as man-eaters; the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) of southeast Asia, and the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) of much of Africa. Both of these species are large, and regularly have large mammals in their diet. Several other species have taken humans, but much less frequently. Many species are too small to consider a person a viable prey choice.

I have never really worried about being attacked, mostly because the two species I’ve encountered most often are not known as regular man-eaters; the American Alligator and the American Crocodile. I certainly give them respect, especially if they are bigger than my boat. I once retreated from a large American Crocodile when it seemed to become very curious about me in my inflatable kayak. I had another encounter in the same lake with what might have been the same 13-footer. I had picked out a nice Mangrove tree to paint, loaded up my kayak with my painting supplies, and set off for the tree. When I arrived, there was that big croc basking next to the tree. It saw me and immediately dove into the water. I assumed that it was gone, and proceeded to set up my easel in my boat and got to work painting. After about 30 minutes, I heard the sound of a large animal right next to me taking a breath. I turned to see that the croc had surfaced so closely that I could have reached out and petted its head. My movement startled the croc and it dove, rocking my little boat. Had the animal actually been stalking me, I’m sure that it would have grabbed me instead of diving. I have encountered alligators regularly during my travels in Florida, but they always seemed pretty laid back. I had a few hiss at me when I got too close, and some really big ones made me cautious, but I have never felt threatened by them. I also don’t tempt them by swimming at night among large alligators, or in spots where people have been feeding them. When I first moved to Florida in the mid-’70s, there had been only a couple of recorded fatal attacks. Since 1973, there have been 24 fatal attacks. A result of Florida’s expanding human population and encroachment into alligator habitat.

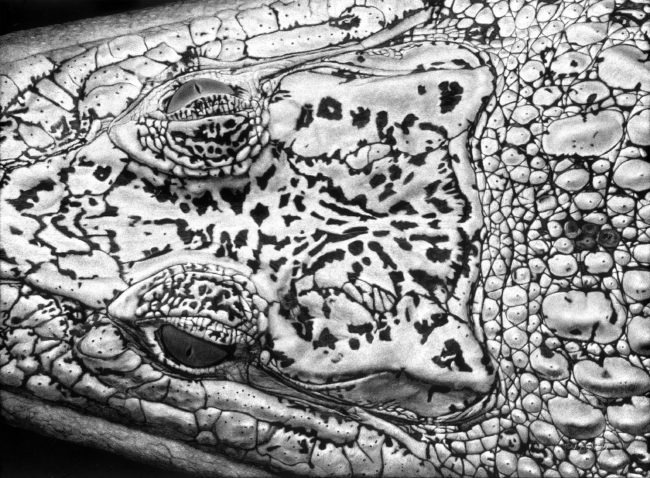

I had been painting alligators since the late seventies in Florida but wanted to branch out in the types of media I was using. In the late eighties, I began to discover the medium of scratchboard. I liked the engraving-like effects it produced. It usually comes prepared as a panel covered in hard, white clay that has then been covered with black ink. You scratch off the ink to reveal the white, creating an image. My scratchboard tool of choice is the Xacto knife, familiar to hobbyists and graphic artists, like a pencil with a razor tip. Scratchboard artists also use tools like tattoo needles, sharped welding rods, or specially made scratchboard tools. Scratchboard is perfect for any detailed, contrasty image. I initially used it to portray the landscapes of caves, as it reproduced the textures, bright highlights, and inky shadows of caves very well. It was also a great medium for doing reptiles with all of their scaly textures. As I began to experiment with scratchboard drawings of crocodilians, the idea began to hatch of doing a show of just crocodilians. It is a group of animals that certainly deserved more attention. The public’s understanding of crocodilians is usually limited to whatever they’ve experienced in popular movies. I hope that my work will give them a deeper insight into the complex and interesting lives that crocodilians lead. I believe that once people understand and appreciate the true nature of these animals, they become more interested in preserving crocodilians and their habitat.

In developing a series of images for this show, I not only needed good field experience with as many species as possible but also good photos as detailed references. This is because I want my work to be accurate down to the last scale. Herpetologists notice such things. Having lived in Florida for several years, I had plenty of alligator references and could get more without too much effort or expense. I had to travel further abroad to get some references… to Borneo and Thailand for the Tomistoma, Saltwater and Siamese Crocodiles, the Amazon for various Caiman species, and Africa for the Nile and Dwarf crocs. And, there were always crocodile farms (in Thailand and Malaysia) or alligator farms (St. Augustine, FL) that had the rarer species that I could photograph.

After I had gathered the right images for a species, I would develop a sketch of what I felt was the most interesting angle, using the lighting and scale details to fill it in. My drawing process is glacially slow because I want to do the best-detailed rendition possible. My daily goals amount to completing about a square inch or two. I normally begin the scratchboard by making a tracing of my original sketch, and then I transfer it to the scratchboard surface by covering the back of the tracing with chalk and tracing over the image again onto the scratchboard. Once I have a map to guide me, I can begin engraving. I do it this way, rather than developing my image directly on the board because mistakes are very difficult to fix. I follow the map I’ve created with my Xacto knife, doing stippling at first (tiny, tiny dots) to create my base forms and values. Once the stippling is done, I begin adding brighter areas by cross-hatching over the stippling. Some scratchboard artists use tools like fiberglass brushes, steel wool, or airbrushes to achieve soft effects, but I like the vivid lines and dots of direct scratching, like the engravings in old zoology textbooks.

Many of my works are portraits, and some depict behavior. All, I hope, go deeper than mere illustrations of species. Crocodilians have their own aesthetic of texture and form, hewn by 200 million years of evolution’s trial and error. They’ve seen the advent of flowering plants, the rise and fall of the dinosaurs, and mammals go from tiny rodents to elephants, the Blue Whale, and man. I just hope that they survive us, too.

Biography

John Agnew began his career in natural history museums, where he has designed exhibits, produced illustrations, and painted murals and dioramas for museums and zoos around the country and as far away as Moscow. Since the early ’80s, John has produced nearly thirty thousand square feet of murals and dioramas in the Cincinnati area for the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science, the Cincinnati Zoo, Cincinnati Parks, and Hamilton County Parks.

His smaller paintings of natural history subjects are in collections around the world. He is a Signature Member and a member of the Executive Board of the Society of Animal Artists, and a founding member of Masterworks for Nature. He has participated in major exhibitions of realist work, including Art and the Animal, Arts For the Parks, and Birds In Art. In 2007 he was the Grand Prize winner of the national juried show, “Paint the Parks” and received an Award of Excellence in the Society of Animal Artists annual show, “Art and the Animal.” In 2009 he received the “Patricia A. Bott Award for Creative Excellence” at “Art and the Animal.” In 2012, he received the Ronald David Smith Memorial Award at the Kentucky National Wildlife Art Exhibit. He has published many limited edition prints and in 2001, North Light Books published his book, “Painting The Secret World Of Nature.” His work has been featured in Artist’s Magazine, Reptiles magazine, and others. In 2009 he was named Artist in Residence at Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, and in 2011, he was named Artist in Residence at Everglades National Park. He has traveled worldwide in search of his subjects, including Borneo, Thailand, and the Peruvian Amazon in addition to much of the United States. He is represented by Miller Gallery in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the Tang Gallery in Bisbee, Arizona.

John Agnew’s traveling museum exhibition is scheduled in 2021 at The Chicago Academy of Sciences Notebaert Nature Museum and in 2022 at the Hiram Blauvelt Art Museum near New York City.

CROCODILIAN SCRATCHBOARDS by JOHN AGNEW

Produced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C.

Information about the exhibition is available at:

https://john-agnew-jzhf.squarespace.com/crocodilian-scratchboards/?p

This blog is part of MAHB’s ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT II series, a travelling museum’s exhibition.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org