Essay excerpted with permission of Author from:

The Wildlife Art of Ron Kingswood

You could say that Ron Kingswood is a wildlife artist. But I would say, only to a certain degree. Some of his work barely pictures wildlife and some not at all. Were one to skim through a catalogue raisonné of his paintings, one would see a body of work characterized by stylistic periods shaped by nineteenth- and twentieth-century art movements, structured by compositional layers with an evolving ecology and environmental ideology, in grand scale.

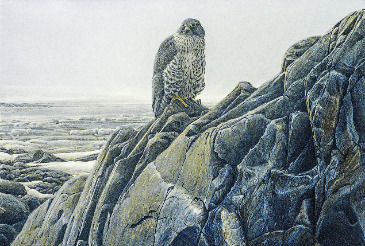

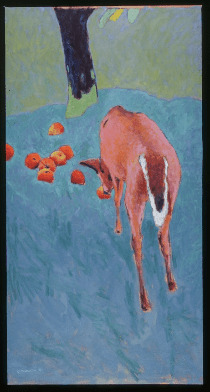

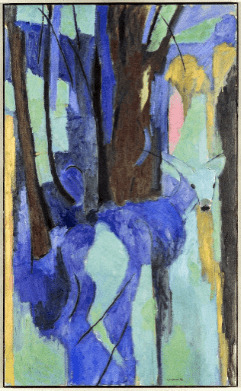

Kingswood’s early professional work, through 1985, had a strong affinity to that of his elder, countryman Robert Bateman (such as Gyrfalcon, left), which is understandable given Kingswood’s predisposition to nature as a young man, and Bateman’s artistic dominance in Canada and the U.S. During Kingswood’s middle years, from 1986 to 2015 or so, he drew upon art history lessons he had learned as a student at H.B. Beal Art in London, Ontario, which he visually integrated with wildlife ecology and environmental ideology. This resulted in several series of work influenced first by Impressionists including Cézanne and Monet (e.g., Out of the Dimness They Sounded, left), then Post-Impressionists particularly Matisse (Deer in Orchard, below), and German Expressionists such as those in the group, Der Blau Reiter (Dusk with Deer, below), and Abstract Expressionists and Minimalists from Mondrian to de Kooning, Motherwell, and Rothko (e.g., Pick Pocket below, and Takken in het bos and Snow Buntings below), all of which, it is safe to say, has rarely had much influence on painters of wildlife art with the exception of a few such as Robert Bateman.

In the New Millennium, Kingswood reduced the degree to which wildlife subject matter visually dominated his paintings (e.g., Pick Pocket, Takken in het bos, Snow Buntings), focusing instead on bold composition of ecology resulting in a dominate sense of place and increasingly, environmental ideology such as his ardent stance against industrial clear cutting of forests. More recently, the artist has been layering his painted environments with wildlife images. And this postmodern, blending of historic styles and content is what viewers predominantly see in Ron Kingswood’s artistic output today (e.g., Northern Vigil, Gyrfalcons).

Ron Kingswood was born and raised in Southwest Ontario midway between Toronto and Detroit along Canada’s Lake Erie shore which is about 60 miles north of the U.S. His father raised him with an understanding of hunting and sportsmanship: “I recall most Saturdays during the fall hunting season traveling with my Father to the country to meet my uncles where we would wander woodlots and meadows hunting pheasants, rabbits and ducks.”

It wasn’t long before young Ron, began to draw and paint his quarry. This interest led him to a serious study of nature through magazines such as Audubon which featured illustrations by Don Richard Eckelberry (1921-2001) and, Canadian, J. Fenwick Lansdowne (1937 – 2008), both of whom Kingswood wrote to solicit advice, and both of whom replied. “They were the first to inspire me as a very young bird painter.” “Years later, during my honeymoon, we visited Eckelberry in Babylon, on Long Island, New York, and often since.” (Author’s note: Eckelberry was widely revered during his lifetime by North American wildlife artists. His willingness to mentor Kingswood was generous, but not all that unusual. In the world of wildlife art, a number of old masters mentored younger artists over the years, notably Louis Agassiz Fuertes, whose protégé, George Miksch Sutton, published their correspondence in a book entitled, To a Young Bird Artist.)

In 1978, The Lynwood Art Centre in Simcoe, Ontario, held a Robert Bateman exhibition. Kingswood made the one-hour drive to see the show in person with his older brother. Bateman was a teacher in Burlington, Ontario, at the time, an hour further east. The experience obviously motivated Kingswood. In 1979, he enrolled at H.B. Beal Art (school) in London, Ontario, to formally study art, and it was there that he discovered art history: “When I finished the program, I realized what had excited me there the most was art history.” “I plunged head first into reading any book I could find; first the Impressionists then the rest followed as art history unfolded before my very eyes.”

Among highlights, were Cezanne, who taught me that everything in a painting needed the same care and handling whether trees, figures or buildings. This was not what I was seeing in the wildlife art world where the animal was the focus and background was very much secondary, with the exception of Bateman. Then I studied the great Matisse, who was a huge sway for me. Matisse was in his early 40’s (to my great amazement) when he started to think independently, removing himself from tradition, and starting to develop his own vision, perspective and insights on painting. . . . I also studied the life of the great sculptor, Brancusi, who was a student of Rodin. To establish himself, Brancusi said that he needed to leave the studio of Rodin, because he felt that he would be forever in the shadow of the great tree. So somewhere in my 40’s, after seeing and reading plenty about the world of modern art and the world of animal art, I (realized I) needed to heed what Matisse and Brancusi said many years before.

–Ron Kingswood

In his reminiscences about his art and career, Kingswood is quick to recognize his wife, Linda, for all that she has done to help him establish his career.

We at the National Museum of Wildlife Art have long admired the work of Ron Kingswood. His experimentation with abstraction not only allows us to talk about different art movements, but also about different ways of interpreting nature. We have an enormous canvas of his called Mink Tracks, Canada Geese that is mostly Kingswood’s depiction of snow. In the lower left corner, cut off on the edge of the canvas, is a group of geese. In the upper right corner is a small patch of open stream and a few carefully placed dark circles (the mink tracks). I like to tell people that it is a very large painting of a very small patch of land. Furthermore, it is something you might see right outside our front door on the National Elk Refuge; it just depends on where and how you look. Kingswood’s work helps us broaden visitors’ expectations of what they will see when they enter our galleries and hopefully broadens their idea of what wildlife art can be.

–Adam Duncan Harris, Ph.D. [Jackson Hole, Wyoming] Peterson Curator of Art and Research, National Museum of Wildlife Art of the United States

Ron Kingswood defies convention, he challenges rigid established boundaries, he pokes a paintbrush into the eyes of the status quo and declares that those who celebrate nature in their art can do better. Throughout art history, irreverence has been the amniotic fluid for new exciting art movements to be born. Ron isn’t an iconoclast because he doesn’t care what people think; he is who he is and does what he does because he cares deeply about the plight of the natural world in the 21st century and his fabulous paintings are coming off the easel to wake us up… Kingswood is using fine art to advance a harmonic fusion between the aesthetics of fine art, composition, form and color with a message that there’s so much depth, so much happening within the realm of natural beauty that we need to make visible. In many ways, he is nonpareil and he is only just getting started. Kingswood is avant garde and that’s a very good place to be.”

– Todd Wilkinson [Bozeman, Montana] Environmental journalist, longtime American writer about wildlife art, and author of the recent critically acclaimed books, Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, an Intimate Portrait of 399, the Most Famous Bear of Greater Yellowstone and Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet. Wilkinson wrote a major review of Environmental Impact, a traveling museum exhibition produced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C., which included the work of Ron Kingswood, for Sculpture Review Magazine which is published by The National Sculpture Society.

Ron Kingswood’s works will be featured May 2016 in The Wildlife Art of Ron Kingswood Exibition at the Jonathon Cooper Gallery. Learn more here.

David J. Wagner, Ph.D. [Milwaukee, Wisconsin] is the author of American Wildlife Art. He is also President and Chief Curator of a company that produces traveling museum exhibitions. Among its recent exhibitions is Environmental Impact, which toured to eleven venues coast-to-coast in the United States, and featured Clear Cut, 2003, Oil on Canvas, 60×54; and Takken in het bos (Forest Succession) 2005, Oil on Canvas, 100×90, by Ron Kingswood.

End note: Quotes and biographical details for this article were provided by phone and email from the artist to the author between October, 2015 and February, 2016.

2016 © David J. Wagner, Ph.D.

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.