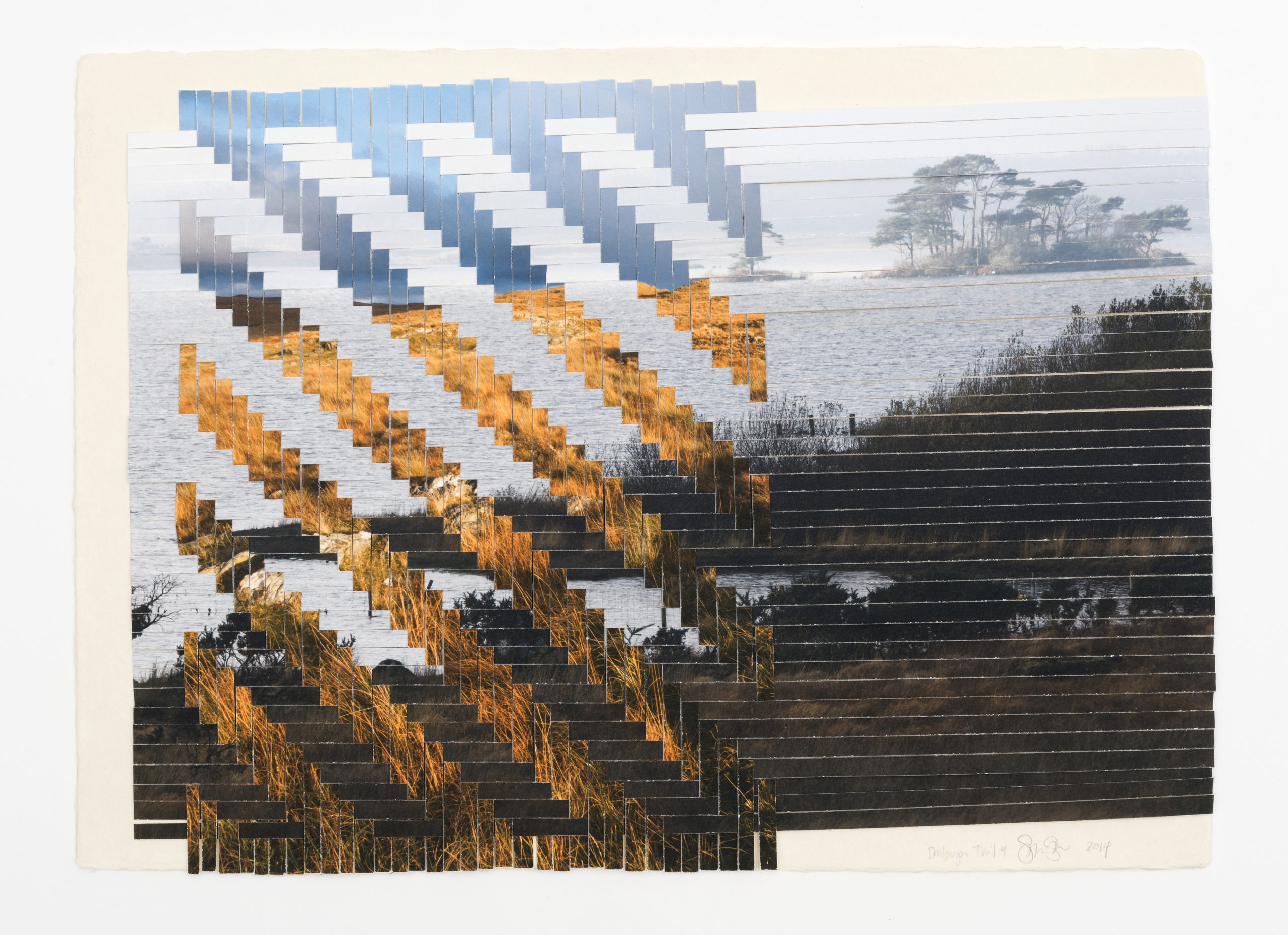

Sarah Sense – Doolough Trail 4 (detail) – Photo courtesy Sarah Sense © 2021

This is the last piece of four interviews in the series

Disclaimer: I do not support the tokenization and extraction of Indigenous knowledges and people. Upholding ways that respect and honor Indigenous knowledges and people is of the utmost importance. Every Indigenous interviewee and artist has given me their consent to share their words for this piece.

Cameran Bahlsen

Series Conclusion

I want to first express my deep gratitude to all who participated in this four-part series. Sensitive and important topics, issues, and themes were discussed in each piece, and I want to thank the artists and interviewees for their vulnerability, openness, and strength. I am forever thankful for the relationships and connections I have made with such amazing Indigenous folks throughout this process and for what I have learned from each and every one of them. As a reader, I hope you have learned from their voices and creative visions as well.

Through a “two-decade long” collaborative research paper completed by systems scientists, the core values of Indigeneity are found to be “Relationship, Responsibility, Reciprocity, and Redistribution”, also known as the “Four R’s”. As witnessed in my interviews with Emily, Hawk, Corina, and Shanny, these values are especially evident in their approach to addressing the climate crisis. Even with voices from different tribal affiliations, locations, and backgrounds, the overarching beliefs of how to properly foster a relationship with Mother Earth was extremely similar in their responses, and I think that is what is so unique about Indigenous voices.

I truly believe it takes courage and humility to de-center oneself and think about the world in a spiritual sense- not just in a Western, scientific sense. It is our duty towards our non-human and more-than-human relatives to enact this mindset shift. You do not have to be Indigenous to feel a connection with the land, trees, and water. Without the inspiration that comes from feeling bonded to our Earth, it is evident that consumerism quickly takes over and relationships falter. The “Four R’s” are values that can and should be held by every human being as a way to develop meaningful connections to the land and to other humans.

Inspiration comes from diverse voices of the planet, and I hope the world can continue to realize this and look to the environmental wisdom of Indigenous peoples as something to understand, follow, and protect. Listening and learning to those of all cultural backgrounds has never been more crucial in our navigation towards climate resilience.

Spoken Interview with Corina Roberts

Cameran Bahnsen: What are the defining aspects of how Indigenous people view the Earth?

Corina Roberts: Our World is Relational. The biggest difference between the indigenous world view and the capitalistic world view is relationship. Indigenous cultures recognize, embrace, respect and appreciate our oneness with our home planet. “Mother Earth” is not a slogan. It is a relationship. It is a recognition that our breath is one with all things and provided by the Earth, by her plant nations; that as we exhale we feed them…and so, we must care for the Earth as she cares for us.

CB: What traditions or stories have shaped how you view and treat the Earth?

CR: Leaving offerings for what we take is a powerful way to build a relationship with our surroundings, and teach respect. It is a very simple and yet very powerful way to shift human consciousness. Tobacco is often given as an offering or as a prayer, but not all cultures have or use tobacco; corn meal can be used, a bit of one’s own hair, or failing any physical offering, a prayer, a song, a gentle embrace with the hands.

Sarah Sense

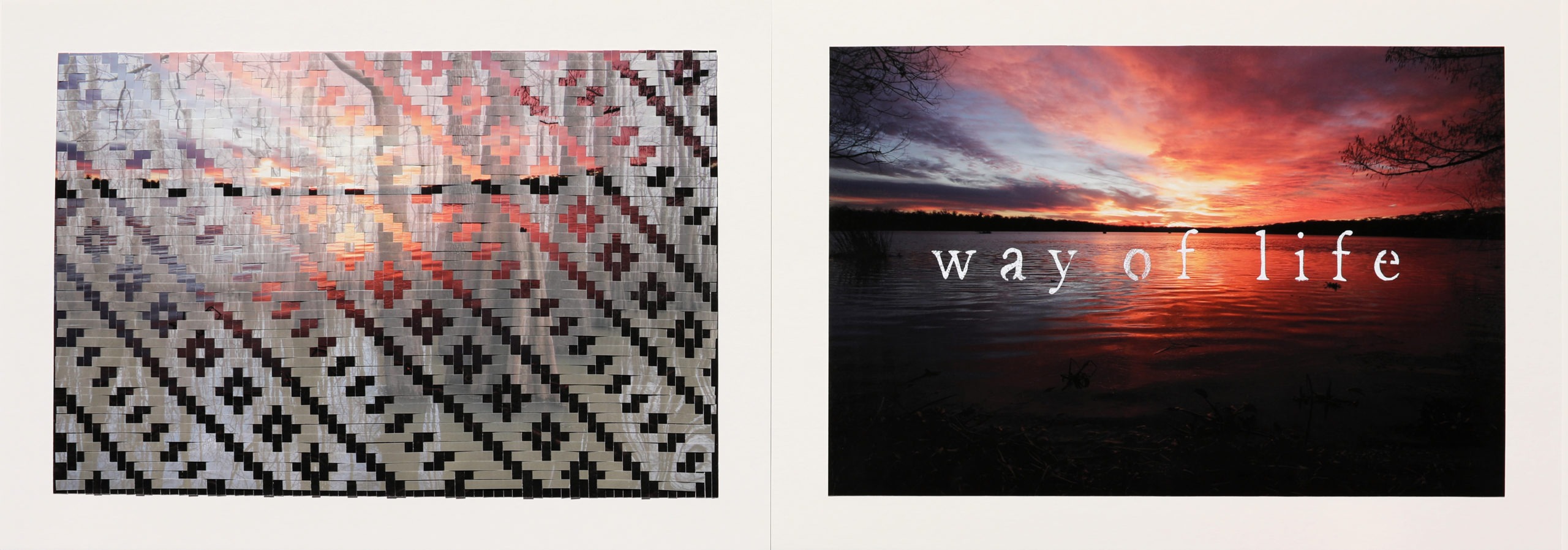

cypress Series: Way of life

2017

woven archival inkjet prints on bamboo paper and rice paper, wax, artist tape, acrylic paint

16″ x 48″

cypress Series Description

Bayou Teche is the main water fixture on the Chitimacha reservation. The bayou and surrounding waters are home to cypress trees. The roots to these mysterious trees grow into the earth and then through the water, reaching for the sky while their knees, reach through the water for oxygen. This past January, I was taken on a fishing boat journey through a cypress swamp, just on the cusp of the reservation, which is where I captured the images for the series, cypress. To reveal the emotional relevance of the cypress to the Chitimacha community, I asked community members to describe the trees in one to three words. I then stenciled their words onto the photographs. The Chitimacha basket weaving of the photographs gently reveal a pattern from a Chitimacha basket in my personal collection.

Working primarily with Chitimacha basket weaving techniques, I create both flat mats and baskets to make social and political statements. More recently my work has focused on land and family, and more intimately relationships to the two through spirituality. For this body of work, I chose to begin with the location of the reservation as a space that I feel connected, although I have never lived there. It is that special connection that I wanted to articulate with both simple language and weaving.

CB: What do you think Western cultures can learn from Indigenous people when considering global environmentalism?

CR: Reciprocity…replacing, giving back, not just taking. The Mother relationship. The stewardship of the planet across boundaries. And the understanding that EVERYTHING we do has an impact on the planet. The principle of Mitakuye Oyasin, a Lakota phrase meaning All My Relations or We Are All Related, which gives us both a sense of belonging and responsibility. Not taking more than you need is an important part of this which, unfortunately, does not translate well to the corporate capitalism model. But it does translate to individual consumerism.

CB: What does the current climate crisis, often understood to include ecosystem/habitat loss, depleting natural resources, loss of biodiversity, and changing climates, mean to you?

CR: It is a very direct relationship because I live in a forest and see the effects of climate change daily. Habitats are changing. Trees are retreating to higher altitudes or dying off altogether. Replanting them is no longer a feasible means of fixing the problem because the climate itself no longer supports them. Animals that really should be wild are becoming increasingly habituated to cities where they find water and food for the taking. Loss of biodiversity is rampant as invasive species take over landscapes and replace the native flora and fauna. Those are just the elements I witness personally. When we change an environment, we lose everything it contributes to the health of the local and global environment, and when we affect the climate through our global actions, we change the natural rhythm, the breath of the living planet. We disrupt the skin and the vascular system and pollute the waters, the vital fluids of the planet; if you can imagine the Earth as a living, breathing organism with a circulatory system, a digestive system that continually recycles material, a core made of heat, you can begin to understand why mining and forest clearing damage the planet in ways that we do not comprehend from a capitalistic viewpoint.

CB: How can Indigenous ways of understanding the environment allow us (humans) to change our relationship with the Earth?

CR: If the understanding can be translated…heard, understood, illustrated and given value, such as, you will have a more sustainable and popular product if you practice better principles…if the understanding can be translated somehow to make sense to the ridiculously wealthy, it can change how we live. Ten percent of the humans on the planet consume 90% of the resources, I am told. How do you make moderation and reciprocity attractive to the uber-rich who live so far beyond the means of the rest of the word and can have anything they want that they do not have a like sense of reality to the rest of us? How can you reach people who have that never-enough disease? Reaching them somehow is critical. Because to reach one of them is the same as reaching a million ordinary people.

Sarah Sense

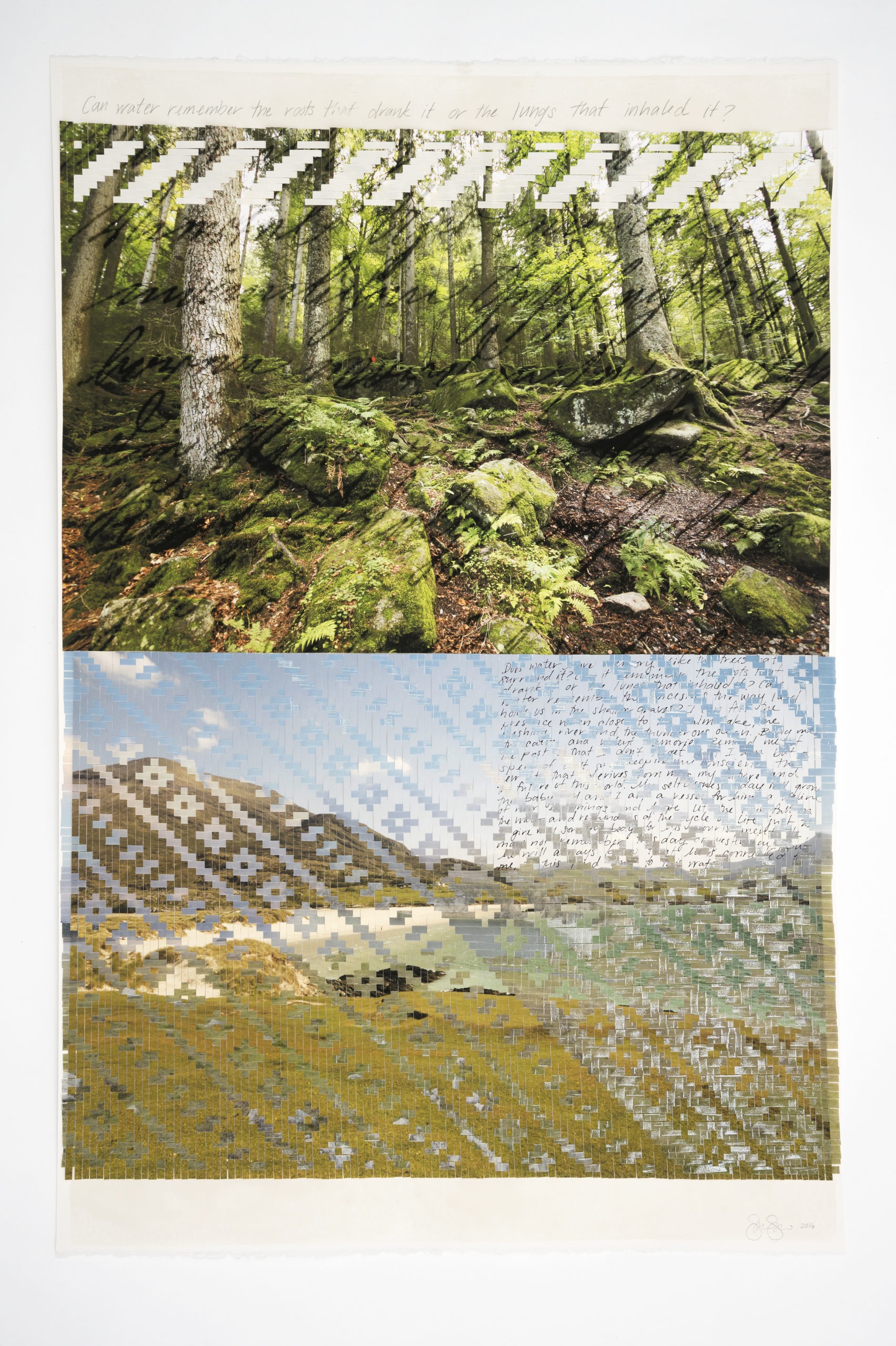

Remember Series: Remember 4

(Read the description of the series below the next image in the article)

2016

45″ x 30″

Arches watercolor paper, archival inkjet prints,

bamboo paper, rice paper, tape, wax, thread, graphite

CB: Is it important that the global citizenry activate Indigenous ways of knowing?

CR: Yes, because in its absence, there is nothing but mindless consumerism.

CB: Is it possible/appropriate to bridge the gap between traditional Indigenous environmental approaches and scientific knowledge to contribute to a more sustainable future?

CR: Yes, absolutely. Several key things need to happen. There needs to be generational support within the indigenous community – so that the wisdom of elders who still have the wisdom are heard and their way of talking is faithfully translated to something we can understand today and so that young indigenous people who move into the roles of leadership do so firmly grounded in that ancient wisdom and not immersed in modern science. To this moment much of what we do in the name of environmentalism is disastrous… like removing lawns instead of just letting them die back…grass holds moose in the soil and emits water vapor into the air; when you lose grass you make the climate hotter…when you release grass with a rock landscape you lose the utility of the space and put in the place of calling grass something that holds and re-radiates heat…not to mention that trees which fed on the watering of the grass now die…we don’t think things through to the end, we just call ourselves environmentalists and do things that in the end make everything worse…

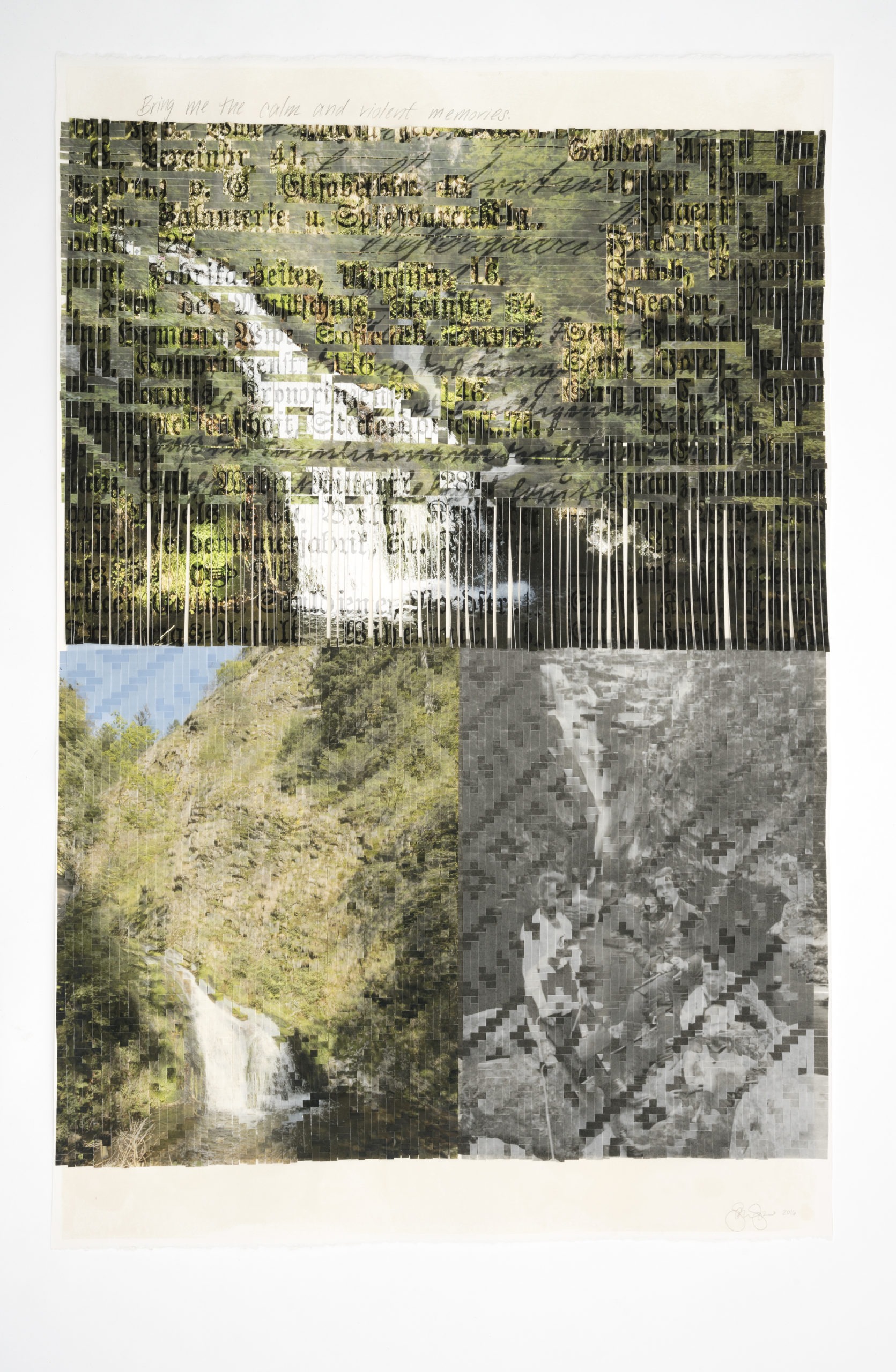

Sarah Sense

Remember Series: Remember 2

2016

45″ x 30″

Arches watercolor paper, archival inkjet prints, bamboo paper, rice paper, tape, wax, graphite

Remember Series Description

Does Water have memory? How is one connected to land? How is one connected to water? Through careful manipulations of images depicting family locations of birth and death, I explore location of self within relation to location of land. These works ask the questions of how the physical self is attached to physical locations, while the spiritual self exists within parallel dimensions that are tied to ancestors. These questions of our connectedness to land: where we are born and where our ancestors are from become a riddle of immigration, both forced and volunteered. By revisiting land and archives of past family, I hope to revisit memories of the past through still, meditative moments that connect me a location that I may be visiting for the first time. The images, patterns and text in these works, Remember, explore my family histories from Chitimacha, Choctaw, Germany and relations to Ireland. The patterns from the woven photographs are traditional Chitimacha basket patterns from my family, while the text is my Choctaw Grandma Chilie’s stories re-written by me alongside my own writing. The landscapes are a combination of the Black Forest in Germany and Connemara, Ireland.

CB: What are some community approaches to addressing the fact that Indigenous communities are often disproportionately affected by climate change?

CR: Awareness campaigns, although those can be easily ignored by the media. Legal action is good, but as we are learning in places like the rain forest, if indigenous people make legal victories, you can just light their forests on fire and kill the individuals who oppose you. Still, we have to do all of this. We need better media presence and somehow, we need to craft messages that people who are not native can relate to and be moved by.

CB: What do you see as the largest barriers to enacting the change we need to see in order to live more sustainable lives and protect the Earth’s resources?

CR: Our government is owned by corporations. And the people don’t rise up for the most part because they are so busy trying to make a living there is no energy left for fighting the government. We need a new government. Europeans need to choose our next President. Americans have lost their way, either because they care only to protect their own interests, or they are too poor, too disconnected, too stressed and too involved in petty consumerism to look beyond themselves. We are not connected. Not to our land, or each other. We are nuclear families lacking a sense of global community.

CB: What support do you and/or your community need to better address some of the challenges and problems we’ve discussed today?

CR: Generational continuity. In our organization, it is time to connect with and support young indigenous people working on sound goals locally. That we need to build from the inside. From outside the native community, we perpetually need funding but there’s more than just money. We need to find ways to address issues effectively. We need marketing strategies that mobilize people to become active citizens. Everyone needs to be engaged in doing something reciprocal for the planet and themselves. Ultimately, this is a spiritual revolution that must start from the core of the individual. You can’t change the world from the outside. You have to do it one person at a time from the inside. And there’s so many people. I’m exhausted just from thinking about it. But I’m also cooking up a plan. A plan using art. A plan using the principle of Mitakuye Oyasin. Because I’m tired, yes…but I still have a little something to give.

Sarah Sense

Doolough Trail 4

2014

12″ x 17″

Bamboo paper, archival inkjet prints, tape

Doolough Trail Series Description

My Grandma Chilie is Choctaw and grew up in Broken Bow, Oklahoma. She is a nurse, storyteller, photographer, world traveler, basket collector and writer. At ninety-one she is recording her stories of family, traveling, love, and disappointment. There is a document that she had written in August 2014, called “The Choctaw Irish Relation.” The text that you see in this series is her words, re-written by me. I recount history in two different countries and different communities to bring perspective to an old story, turned legend, which still holds social relevance with compassion and empathy. The story goes: shortly after the Choctaw were removed and displaced in Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears, word reached the community that there was starvation in Ireland. The Choctaw gathered funds and sent the money to Ireland as a gift to help. This gift had such a profound impact that the story lives strong in Ireland today. In telling one Irishman that I was Choctaw he got tears in his eyes. It is a recent past and still remembered. Learning of this story from my Grandmother, and to then move to Ireland feels like a closed circle. To re-write and re-record her experience is like breathing her life into her old home of Oklahoma. The Choctaw basket patterns are from the two baskets that she gifted to me in the summer of 2012 and the Chitimacha basket weave is consistent to the one that I bought from renowned basket maker, John Paul Darden… In this series of work I am showing my gratitude to my ancestors for guiding my journey, bringing me to Oklahoma and for giving my grandmother an opportunity to share her stories.

Afterthought: I want to thank both Corina and Sarah for their kindness, resilience, and drive. I met Corina through an annual, local powwow that her organization, Redbird, hosts every year. This powwow has provided a space, home, and spiritual gathering away from our traditional homelands for my family and I. Community for urban Natives is incredibly crucial, and Corina is doing amazing work for providing that community for tribal members of all backgrounds, which truly speaks to her character. I met Sarah through a connection with the de Saisset Museum, and I commend her for all she has done within the art realm, and for what she has done with our people as well. It is evident that she cares about her family and cultural roots, and her kindness shines through her work.

Cameran Bahnsen

Disclaimer: The words and art of the featured interviewee and artist are independent of each other and only reflect their own viewpoints and opinions. They are not reflected through each other in any way.

Corina Roberts

Corina Roberts

Corina Roberts is the founder of Redbird, a Native American and environmental non profit foundation which hosts the annual Children of Many Colors Native American Powwow. Her ethnicity is Cherokee and Osage, as well as German/Baltic/Scottish/Welsh. She owns and manages Chilao School in the Angeles National Forest, and is involved in a number of arts, cultural and healing arts endeavors and motorcycle safety. The Chilao School land base is located in the heart of the Angeles National Forest where there are many vehicle collisions and accidents every year. Here, she is responding by offering opportunities to learn skills that will reduce the likelihood of a preventable accident. She is also the proud “mom” of some amazing animals; Koda (pictured), and Winnie, her sister, six years separated. Both dogs were abandoned with littermates in an industrial park. Winnie is a local celebrity with her gentle and funny disposition, and Koda is special too- despite her fractured right hind tibia, she is a romping, stomping, wild pup.

Sarah Sense

Sarah Sense is an artist from Sacramento, California (1980). She received a BFA from California State University Chico (2003), and a MFA from Parsons the New School for Design, New York (2005). Sense was the curator/director of the American Indian Community House Gallery (2005-07) where she catalogued the gallery’s thirty-year history. Sense has been practicing photo-weaving with traditional basket techniques from her Chitimacha and Choctaw family since 2004. Early works are based on Chitimacha landscape in Louisiana and Hollywood interpretations of Native North America. When Sense moved to South America in 2010 for research, her work changed to include travels journals, landscape photography and family archives, telling stories to reveal Indigenous histories, most notably her field search of Native art from twelve countries in the Western Hemisphere, for the book and exhibition, Weaving the Americas in Valdivia and Santiago, Chile (2011). After, she traveled to Southeast Asia and the Caribbean for, Weaving Water in Bristol, England (2013). While living in Ireland she collaborated with her Choctaw grandmother for Grandmother’s Stories in Tulsa, Oklahoma (2015), followed by works about family lines and motherhood, Remember in Frankfurt, Germany (2016). Sense continues her research as a British Library Eccles Centre Visiting Fellow (2019-20) and recently installed a sculpture at the National Marine Aquarium (2019) Plymouth, England.

Sarah’s Website.

Cameran Bahnsen

Cameran Bahnsen

Cameran Bahnsen was raised in Ventura County, located in Southern CA. She is part Assiniboine (Fort Peck Reservation, Montana) and currently attends the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is pursuing a B.S in Environmental Studies with a minor in American Indian and Indigenous Studies. At a young age, she grew up beach camping with her family, which inspired an early love for the outdoors. Her love of nature, coupled with her cultural connection, continue to drive her aspirations of working within resource management, environmental education, interpretation, tribal relations, and conservation. She enjoys hiking, camping, backpacking, cooking, listening to music, and spending time with friends and family.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

This article is also part of the MAHB Arts Community‘s “More About the Arts and the Anthropocene”. The MAHB recognizes the value and importance of learning and listening from Indigenous people. In an effort to honor Indigenous voices, if you are an artist that identifies as Indigenous and you are interested in sharing your thoughts and artwork, as it relates to the disrupted but defining period of time we live in, please contact michele@mahbonline.com