We are pulling three live bonitos bridled to light leaders without hooks, close behind the game boat, 80 miles offshore the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Sitting on the covering board three divers with pony tanks and cameras, including myself, scan the clear deep blue water of the wake with anticipation, adrenaline running high. We are patiently waiting for a blue marlin to glide into the spread to eat one of the tempting bonito.

Kaboom! Out of nowhere a big fish explodes on the port side bonito, and the attentive mate immediately yanks the halyard, and the bonito flies into the air out of reach of the ten-foot-long predator. We hit the water. I land in a cloud of bubbles beside the 300-pound marlin as it races across the stern to catch the starboard side bait, its streamlined body dark, almost black, its magnificent tail glowing fluorescent blue as it goes past. Its fins are erect for increased maneuverability at high speed and its blue eye is all-seeing, does not miss a thing in the unfolding drama below the boat. I swim hard to follow it as it crashes the bait in a burst of foam, but the crew flips the bait out of the water again, the fish turns in its own body length and races past us again going for the port side bonito…

One cannot go to the local aquarium to see a marlin or sailfish, or in any other captive facility. They do not survive as they need space to move around. The billfishes (marlins and sailfish) are amongst some of my favorite subjects to paint. But for reference, you have to invest the time and effort to swim with unhooked fish in their open ocean environment. These fish are cosmopolitan in tropical seas and one of the best places to encounter them is in the eastern tropical Pacific, along the coast of Central America, particularly Costa Rica and Panama. We pioneered the way to swim or dive with teased-up billfish in the early nineties, and have filmed each of the nine species in the ocean making documentaries about each one. Swordfish, though similar in morphology to billfishes, is classified in a separate family of fishes.

Unlike researching North American big game or African animals for art subjects, where one can spend hours and days in the field looking at wildlife, even with binoculars for reference, we have just seconds, perhaps a few minutes with a rampaging blue marlin before they lose interest and vanish into the blue in search of prey. Sailfish and striped marlin may stay longer particularly if there are several fish in the group. The color changes that happen range from the dark predatory hues often with vivid fluorescent stripes on their arrival, changing to subdued pastels blues and turquoise which is their “traveling” color phase. They are camouflaged against the blue background.

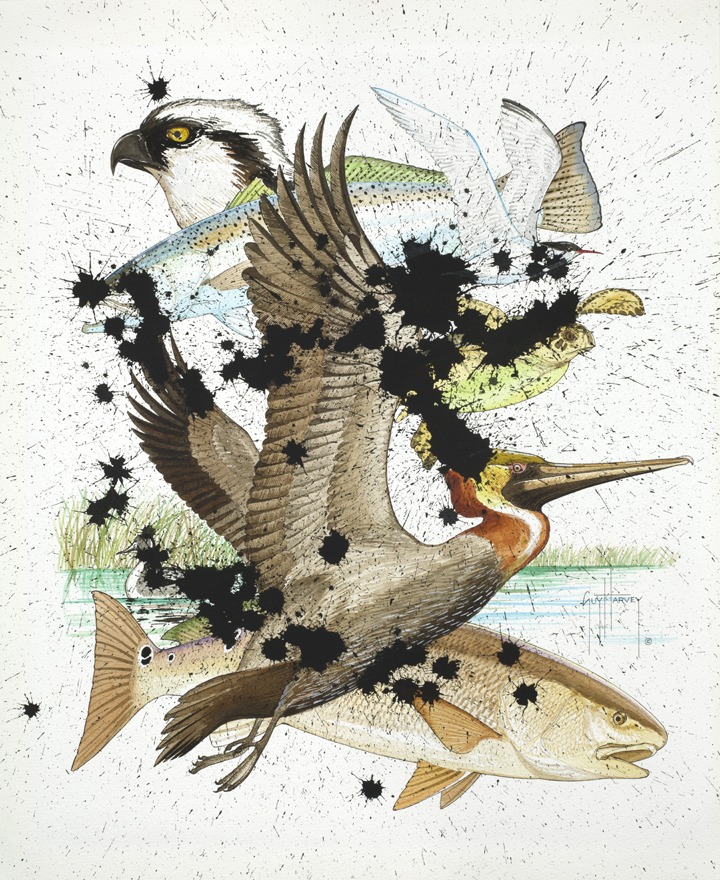

Natural predator/prey interactions of billfish can be found in certain places where striped marlin (Cabo San Lucas, Mexico), white marlin (Venezuela), or sailfish are feeding on schools of sardines (Mexican Yucatan). Sometimes there are other predators in attendance as well, different species of sharks, whales, dolphins, and sea lions to name a few which add a different element into a painting.

To swim with these high adrenaline predator/prey interactions is one of the most exhilarating experiences one can have underwater. In 2000, America’s most famous wildlife sculptor, known for his monumental work, Kent Ullberg, and I spent four days with diving striped marlin, sailfish, Bryde’s whales, and sea lions feeding on sardine bait balls off Magdalena Bay, Baja, in one of our most memorable open ocean encounters. Because these fish are big these scenes demand a big canvas – 8 feet to 15 feet long. The interaction of the bait with the surface generates a lot of foam as does the passage of the marlin’s massive body through the surface in a chase. Sunlight dapples the bodies of the prey species and the predator. A painting comes to life.

Billfish are harvested for food in many countries, but increasingly this family of fish has been designated for sport fishing use only. Catch and release fishing for billfish attracts very high-end tourists and is the sustainable use of a marine resource. The Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation (GHOF) has funded, and the Guy Harvey Research Institute (GHRI) has conducted, a great deal of research on the migrations and post-release survival of billfish (GHRItracking.org).

Survivability is very high (98%) and many billfish have been recaptured after months or years at large, providing valuable data about annual migrations.

To reduce the consumption of this valuable species, banning the importation of Atlantic billfish into the US was implemented two decades ago. More recently, the GHOF was part of the action taken by a group of organizations that brought about The Billfish Conservation Act of 2018, which now prohibits the importation of Pacific billfish into the US, closing off the supply of billfish from Central America and Hawaii.

Another good example of how effective marine conservation can be is the story of the recovery of the Nassau grouper in the Cayman Islands, where we have lived since 1999. The Nassau grouper is a beautifully marked fish, just awesome to paint in a coral reef scene. It is the iconic reef fish of the Caribbean region and it is very interactive with divers. This is a long-lived, medium reef predator that grows to forty pounds and lives a solitary existence until January or February each year. Over the full moon in January, Nassau groupers leave their home reef and migrate along fringe reefs throughout the Caribbean to a spawning aggregation site or SPAG. Here the gravid females and attendant males gather in large numbers (this used to be in the tens of thousands) and spawn at dusk three days after the full moon. This may happen for three of four evenings in a row before the adults return, exhausted, to their home reef. These SPAGs are used by other fish species (up to 30) at different times of the year.

This reproductive strategy exhibited by all species of groupers and snappers, as well as by other species not so commercially important, has worked well for tens of thousands of years. Until mankind discovered these large aggregations and fished them ruthlessly over the last five decades. Most SPAGs in the Caribbean now cease to function as the fish have all been caught. Those SPAGs with a small grouper population do not work as well because numbers are so low. From a fisheries management perspective, fishing the SPAGs while any species is spawning is complete lunacy. Fishermen were removing the essential broodstock with no consideration for the long-term consequences.

Realizing the gravity of the situation, in 2003 the Cayman Islands Government put a legal fence around the SPAGs, identified in all three islands, and began a research and conservation project. The SPAG with most groupers was at the west end of Little Cayman. In January of each year, our Department of Environment worked with the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF.org) and other fish biologists who make the annual pilgrimage to Little Cayman, one of the best diving places in the Caribbean. The fish are counted each year at the aggregation site, some are fitted with acoustic transducers and some behavioral changes happen.

Also, the fish all change color before the spawning event, going from striped to being black and white. Again an amazing chance to witness and to paint. The spawning begins at dusk with males “caging” gravid females encouraging them to swim fast upward in the water column and discharge their eggs. Many males will accompany each large female until the entire group of thousands of fish does this at the same time for more than an hour well into the dark. Filming the spawning with bright lights had no effect on the behavior of the fish.

We joined the research team not only as sponsors but also to make educational documentaries about the recovery of the species. The first documentary “Mystery of the Grouper Moon”, was completed in 2012, then another one in 2017 to show the progress made in five years and how research, education, and protection of the SPAGs, all resulted in the gradual recovery of the species. The adult broodstock has increased from 1,500 fish in 2003 to over 8,000 in 2021. We use this as the perfect example of when all groups, Government, research organizations, educators, and NGOs work together then meaningful changes can happen. Now this formula has been exported to other countries in the Caribbean and the Bahamas and it is having a positive effect.

The protection of individual species does work but a more effective tool in marine conservation generally is the formation of Marine Parks, Marine Protected Areas, and fish sanctuaries. Nowadays, the reef degradation that we are witnessing is in an advanced stage due to overfishing, coastal development, inadequate sewage disposal, plastic waste, and poor agricultural practices. Not to mention the effects of climate change on the ocean and the negative effects of ocean acidification on coral reefs and their inhabitants. So protected areas should be the first corrective action taken rather than the last.

Often the process is drawn out because of politics. We are very fortunate in the Cayman Islands because healthy marine life plays such an important role in our tourism product. The socioeconomic impact of healthy reefs and fish populations shows how valuable living marine resources have become. Shark ecotourism has become a sustainable use of sharks generating millions of dollars per year in Florida, the Bahamas, and small island states throughout the tropics, without killing a single shark.

This month our marine protected areas (no-take zones) in the Cayman Islands were expanded from 15% of the shallow reef area to 45% and signed into law. The process began in 2011 and spanned several administrations but has now been completed – finally. To quote British marine scientist Callum Roberts “You can have exploitation with protection because reserves help sustain catches in surrounding fishing grounds. But you cannot have exploitation without protection, not in the long term.”

Born in Lippspringe, Germany on September 16, 1955, while his father was serving as a Gunnery Officer in the British Army, Guy Harvey is a 10th generation Jamaican of English heritage as his family immigrated to Jamaica in 1664. From his early inspirations, Guy’s natural gift to recreate marine life has propelled him from Professor of Marine Biology to a Wildlife Artist and Photographer. Guy initially opted for a scientific education, earning high honors in Marine Biology at Aberdeen University in Scotland in 1977. He continued his formal training at the University of the West Indies, where he obtained a Doctorate in Fisheries Management. In 1985, he depicted Ernest Hemingway’s famous fishing story “The Old Man & the Sea” through a series of 44 original pen and ink drawings and displayed them at an exhibition in Jamaica. Based on the positive response he received at the show, he began painting full time and by 1988 had achieved wide acclaim and success. A passion for the beauty and wonder of the underwater world has driven Guy Harvey to be a leading conservationist and advocate for the protection of our environment. He dedicates much of his talent, time, and resources to programs that protect our oceans, fish population, and reef systems. The Guy Harvey Research Institute of Nova Southeastern University and The Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation have taken on a leadership role in providing the scientific information necessary to understand and protect the world’s fish resources and biodiversity from continued decline.

Artworks by Guy Harvey are featured in the current traveling museum exhibition, ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT II (2019 – 2023), and were also featured in ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT (2013 – 2016), produced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C., David J. Wagner, Ph.D., Curator and Tour Director.

Information about ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT II is available at:

https://www.davidjwagnerllc.com/Environmental_Impact-Sequel.html

This blog is part of MAHB’s ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT II series, a travelling museum’s exhibition.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org