Back in 1970 my father, Walter Ferguson, took me on a road trip into the Sinai desert along the Red Sea in our family’s old beaten up olive green 4-door station-wagon Ford Cortina. It was customary to stop along the way for roadkill, where my father would pull over and I would jump out and inspect its condition. If good, my father would put it in a plastic garbage bag to study later, or otherwise, he would take some photos as part of his material collecting process to catalog or even paint for one of his books on Israeli wildlife. It was a very long drive, in part because of the distance and part because of the poor road conditions with many potholes. It was not uncommon to find hub caps along the way that had flown off the wheel as the shock of hitting the pothole would knock it loose.

On this trip, we headed to a beach called Nabk (pronounced as Nabeck) which was a well-known site for mangroves because it was the closest location we could reach and probably the most northern geographic habitat in the northern hemisphere. It was already dark when we arrived, and we were trying to set up our tent with the car’s headlights shining on a level spot of ground. The wind was blowing hard drying up the top layer of the beach and creating a terrible sandstorm. It was very painful as the sand would pelt our faces and get into our eyes, nose, and ears. The tent was acting like a sail, and the pegs we used to secure it to the ground would get yanked out by the wind the moment we turned our attention to the next corner of the tent. As we were struggling, out of nowhere, a local Bedouin appeared and tried signaling to us to follow him as we did not speak Arabic and could not understand what he was saying. We stashed the tent back in the car, grabbed our backpacks, and followed him for a short hike that rounded a sand dune where there were a bunch of Bedouin sitting around a small campfire. A few squatted camels with their eyes closed were strategically placed to provide additional protection from the blowing sand. The howling sound of the wind was replaced with a quiet calm and the occasional crackling pops from the fire.

We were welcomed, signaling us to join them by the fire and offered us some tea. Without knowing each other’s language, it was a bit awkward, but I’m sure our faces showed our gratitude. My father then reached into his backpack and pulled out a pad of paper and a pencil. He started drawing, and as the image of a Fennec fox started to appear, the Bedouin paid attention with little reaction. My father was trying to see if they recognized it, hoping they have seen these in the area, but probably not based on their faces. He then drew a Sinai Hare and got the reaction he expected. The Bedouin perked up and pointed at it, nodding their heads in agreement as they clearly have seen these animals before. We spent a long evening watching my father draw all kinds of desert animals as he was annotating their responses, creating a record of which animals were found in this area.

We were so involved, we didn’t realize that many more Bedouin had joined us coming in from the sand storm and gathering around, including one who was blind. This blind Bedouin carried a hand-made harp used of recycled materials as shown in the picture my father later painted of him. Everything is very scarce in the Sinai desert, mostly sand and rocks with just a little vegetation around the occasional oasis. The harp was made of an old discarded Tin Jerry-can that was used to carry fuel. Although I don’t recall what he used for the five strings, the sound had a calm and slightly eerie tone to it.

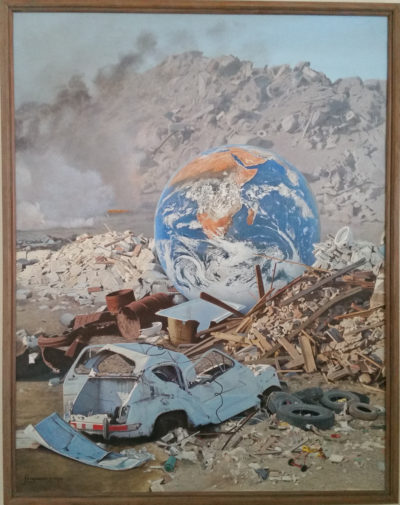

It was obviously a very memorable experience for me as I was only eight years old, and this was just one of many adventures I had with my father growing up. I did not become an artist or zoologist like my father and found my way into becoming an engineer working for the US Navy in San Diego California. But I love exploring the world, especially its natural life and scenery. So seeing the various environments and habitats change over time is a constant reminder of how fragile this planet is when dealing with human activities. Most of my father’s artwork brought out the beauty and essence of wildlife as well as the various cultures and customs practiced around the world, but he also contributed a few works of protest. A few of his paintings are on display now in the “Environmental Impact” traveling show, which are warnings of what’s to come if we don’t do more to protect our planet as shown in his painting titled “Save the Earth”. There is no more obvious statement than this painting depicting the earth tossed into a garbage dump.

It’s in stark contrast to the subtle beauty of the harp made of recycled trash in a land where resources are scarce. Granted that the Bedouin were acting out of necessity and not some larger enlightened notion of protecting the earth, but with this symbolic painting, my father was trying to sound the alarm before it became a global necessity.

This was just the beginning of a series of paintings my father did to showcase human’s impact on the environment. I was working on my Bachelor’s degree in Aerospace Engineering at the time my father finished this “Save the Earth” painting, and we would get into deep discussions about the benefit of space exploration. He would argue that instead of trying so hard to make some inhospitable planet more livable, we should be focused on protecting the already life-supporting planet earth. Of course, I would argue that we should do both as they are not mutually exclusive – many human achievements in the quest for space exploration have translated directly to the benefit of the growing world population. Back in the time of that Sinai road trip, the world population was approaching 4 billion, approximately doubling from the 2 billion when my father was born in 1930. Now, in 2020, the human population is nearing 8 billion while the earth is not growing, and the strains on the environment are visibly worsening.

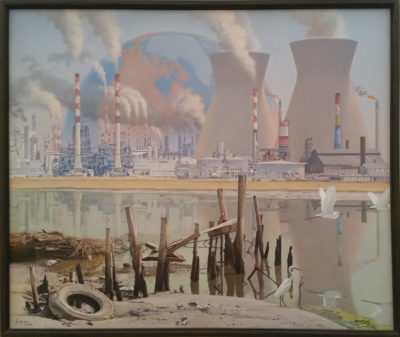

After my graduation, we traveled north to Sacramento and Lake Tahoe with stops along the way, including some amazingly beautiful protected parks like Sequoia and Yosemite. We could not but notice the growing marks of trash and pollution by industrial areas. The oil refineries of long Beach California were spewing out smoke non-stop as if the atmosphere was endless, obscuring the San Gabriel Mountains right until we reached their foothills. There were countless examples of lands in distress, where large forests in the Sierra mountains were clear cut, leaving them bare as if a giant lawnmower rolled over them, and other areas burned by wildfires leaving the occasional blackened stump contrasted with beautiful magenta fields of fireweed.

In a conversation with a tree logger, I had asked why they were logging good healthy trees and not the dead ones killed by the bark beetle – seemed like a tragic waste. The surprising answer was that they did not want to contaminate their logging equipment and exacerbate the spread of their infestation. Apparently, there are fewer freezing days needed to control their population during the winter. Personally, I suspected from my own experience that dry dead trees would wear down their chainsaws much faster than fresh live trees, and that it was more about money.

This trip inspired my father’s next painting on the traveling show with an increasing severity that he titled it “Apocalypse”. In this painting, the earth is like a foreign hostile planet over the horizon where its lands are a bare brown with no shades of life like the desert. The mid-ground view is of a polluted river with a glossy toxic green color reflecting the oil refinery complex. Two of the three Cattle Egrets are seen flying off the canvas in a symbolic gesture of escaping the lifeless environment.

Back home by the beautiful beach of Beit Yanai Israel, we spent endless time taking long walks on the beach, collecting seashells, and of course, any injured animals that would wash up. Used to be more of natural causes like severe storms, but tar and trash have taken over as the more frequent cause. This third painting in the traveling show titled “Save the Seashore” has a glimpse of hope in it, depicting his granddaughter building a sandcastle on the beach despite the trash. Imagine the view without the garbage and the message is clear.

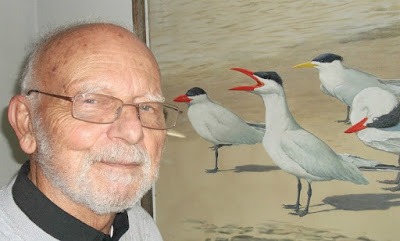

Walter William Ferguson (1930-2015)

Born in New York, Mr. Ferguson received his formal art training under scholarship at the “Yale University School of Fine Arts and at Pratt Institute. He worked as an artist at New York City’s Museum of Natural History and has done illustrations for Audubon and The New York Times. Mr. Ferguson immigrated to Israel in 1965 where he taught briefly at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem after which he became the scientific illustrator for the Department of Zoology of the Tel Aviv University for 29 years. Ferguson has exhibited his paintings in Israel and in the USA, a lifetime member of the Society of Animal Artists, and illustrated many books on wildlife.

Born in New York, Mr. Ferguson received his formal art training under scholarship at the “Yale University School of Fine Arts and at Pratt Institute. He worked as an artist at New York City’s Museum of Natural History and has done illustrations for Audubon and The New York Times. Mr. Ferguson immigrated to Israel in 1965 where he taught briefly at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem after which he became the scientific illustrator for the Department of Zoology of the Tel Aviv University for 29 years. Ferguson has exhibited his paintings in Israel and in the USA, a lifetime member of the Society of Animal Artists, and illustrated many books on wildlife.

Michael Oren Ferguson

Born in Israel and served in the Israel Defense Force for three years before relocating to San Diego California. Received a BS in Aerospace Engineering from San Diego State University (SDSU) in 1991 after which got hired by the US Navy as a federal employee working on Anti Submarine Warfare. While working, continued studying and received an MS in Computer Science from SDSU in 1994, and relocated to Dahlgren Virginia for three years. He then returned to San Diego to work on designing US Navy ship navigation systems. Michael Ferguson published technical papers for professional societies and holds several work-related patents.

This blog is part of MAHB’s ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT II series, a travelling museum’s exhibition.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.