What inspires the creation of an environmental painting? For me, it is a way to resolve important questions about what goes on in our crazy world. Wanting to know the ‘how’ and ‘why’ gives me direction. The painting part is the visual result of my thought processes. The painting comes from part curiosity, and part inspiration. It is a moment in time when creatures and habitat converge with human society. Recognize co-existence. They see us, we see them, and the boundaries are respected. Mostly. The Native-American spiritual idea is that we agree to maintain equilibrium with one another. One not dominating the other, not preying on each other in some primal dance of the winner takes all. It is a way to respect each species’ donation to the whole of successful survival.

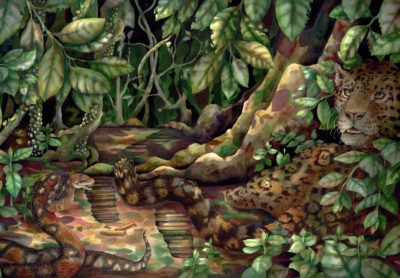

In this watercolor, a relaxed jaguar sits camouflaged on a path near two spent bullet casings, and footprints leading into the forest. What’s going on here? Humans’ invention of the gun has changed the perimeter lines of co-existence. What does that mean for the jaguar, more adept and powerful than any human? Does this gun consign the jaguar to less importance in the scheme of things? The painting delivers the initial thought, but the artwork still contains additional layers of interest for further revelation. What happens, for example in a world where the jaguar always wins? This is the function of great art.

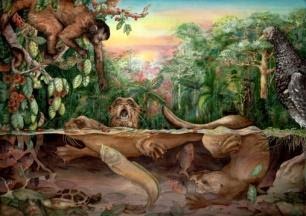

‘Trouble in Paradise’ was created when I was part of a crew filming giant otters for a nature documentary on rainforests in Peru. We talked with native people, and photographed and recorded species in their natural habitats. I spent weeks on oxbow lakes, hundreds of miles from even a dirt road. I watched giant otters fish and raise their young. Intellectually, I knew that these species and environments have been exploited by the outside world and devastated by disease and the pet trade for decades. I couldn’t help but contrast what I knew from the ‘outside’ with the challenge I would face for my survival if I was cut off from all resources. So what can animals possibly do to persuade humanity to back off from devastating the forest environment? I watched those otters for weeks, and on an artistic level, I wondered what this experience meant to them as they swam under our boat with complete trust. Each time they expelled a loud breath with a ‘gruff’ of air, I remembered an old painting that expressed this similar feeling. I knew then the giant otter would be the core focus of another painting.

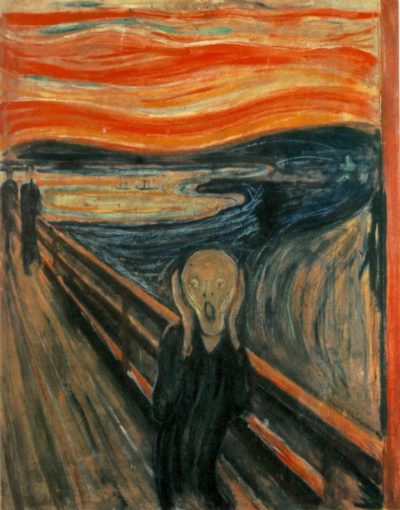

The reason the otter captured my imagination, once home, was verified when I again viewed Edvard Munch’s paintings called ‘The Scream” and read in his journal, that inspiration came when he looked at a blood-red sky with friends near the ocean. He said, he ‘felt a great infinite scream passing through nature when he gazed at this sunset.’ A feeling ‘for an ever-evolving world’s irreversible impact on nature.’ It was then I knew what Munch felt, and what I saw through the otter.

In 2019, unprecedented hectares of forests and grasslands burned. On every continent in the world, we watched as bushfires destroyed 10.3 million hectares in one of the most destructive fire seasons in over 40 years. In the western United States, more than 101,000 hectares destroyed thousands of homes and contaminated forests and rivers. On the other side of the globe, fires burned in Australia, Indonesia, and Russia. In the Brazilian Amazon basin, an estimated 906,000 hectares of forest were deliberately set on fire, leaving species with nowhere to go.

Which generation will demand a moratorium on burning rainforests and polluting oceans? Some people, like me, think we are past the tipping point. But still many buy into the theory that technology stands ready to ‘bail us out’ when crunch time comes.

With the advent of drones, satellites, and instant internet/phone communication networks, there is no way to cheat or hide the devastation caused by human exploits. What is hardest to see is the motive which subversively lies hidden from the consuming public, who would prefer clearly sustainable choices. Scientists are trained to see a multitude of patterns, and clearly see what is changing. The scars of contamination, amplified by 7.8 billion people living off of finite resources, were even more apparent when the Covid-19 Pandemic forced us to hit the pause button. During the shut-down, the air and waterways began clearing.

We live in the center of a giant petri-dish and we pollute and destroy organisms important to the natural resources we all need. We choose instead to encourage gluttonous appetites for ‘synthetically made-things’. We promote a bigger, better, greater illusion that exalts consumption while ignoring checks and balances. Survival is dependent on the overburdened, complex infrastructure required for water, food, and clean air to breathe. We accept the marketing pitch of ‘nature only needs to be managed with technology’ to ensure survival. This is magical thinking. Short-term profits are winning over long-term sustainability. We never get around to accountability because we are following the next shiny ‘tech’ object. A day of reckoning will come.

Our ancestral connection to nature is being ripped out by its foundational roots. Can humanity afford to cut the connection to our biologic roots or should we merge cautiously with intelligent technology? Are we a species prepared for living in a synthetic world? Are self-serving systems trust-worthy, or only endless entertainment, and a virtual distraction, while forests burn and frogs disappear? Are we Gods responsibly in charge of the earth or is our ego in charge?

With the advent of the corona-viruses circulating globally in a matter of days, we must recognize that in the last decades, we have burned 50% of organic resources and are now talking about how to re-engineer them for only human needs. How does that affect everything else? Why can’t we just stop polluting it in the first place? Humans have failed at recreating nature as a full functioning system and we have failed at sustaining life without continuously doing a ‘reboot’. Nature’s interdependent ecosystems are still a bit of a mystery.

While filming nature documentaries in 1989, I flew in an old Russian bi-plane with no doors, over an oceanic expanse of forest, seeing the Amazon rainforest for the first time. Broken only by wild winding rivers, the Amazon is one of the earth’s engines that drive the whole planet. It appeared to be limitless. For miles, parrots flew unimpeded above this green bio-sphere of living things. While walking in this jungle with botanist Robin Foster from the Field Museum in Chicago, I asked; “Why it was that at this part of the trail back to camp it always smells as if someone was cooking onions?” Robin laughed, stopped, took out his pocket knife, and walked over to a big tree and scrapped the bark. He said; “Smell this”. I walked over and a pungent smell of onion and garlic invaded my nostrils and my eyes watered. Seeing my shocked expression, he went on to convey that we were indeed standing in one of the world’s largest living chemical factory. Plants and insects, he explained, are in a constant life and death battle over dominance and survival. Insects and animals are constantly nibbling plants for food. Plants use decayed nutrients to produce poisonous compounds to avoid being consumed before they reproduce. Because of this symbiotic relationship, plants are encouraged to make complex compounds that are the foundation of plants’ chemical defense. It is these compounds humans have learned to exploit since the dawn of humanity. The quantity of new bio-elements being produced by this ever-evolving mass of intact bio-diversity is truly astonishing. To pillage and plunder these assets for the profit and a burger, or for absentee landlords, seems beyond fool-hearty.

Based on this encounter, I decided to paint Diversity vs Destruction, where these two conflicting dynamics meet and show a moment in time where each side is going in opposing directions. What existed before and what is left in the wake of destruction is clear to see. The viewer is then challenged to visually consider cost versus gain. The painting shows the results of our actions.

For the last 3 decades, we have watched and marked on our calendar, the arrival of migratory birds on their way to and from Mexico and South America. The last 10 years we have seen a radical shift. Fewer species and fewer numbers arrive. The multiple years of drought and heat in the west are causing sterilization of the soil that sustains the insect larva that feeds frogs, toads, birds, lizards, and on up the food chain. How does tech solve this? Some species can’t go to a grocery store. ‘Managing Resources’ gets a lot uglier as we reach the edges of earth’s limited petri-dish. Our great-grandchildren will pay, possibly with their lives. They will be deciding who lives, and who dies in a compromised climate of violence, servitude, and deprivation when things run out.

I stand beside my fellow environmental artists and I agree with the value of what one bee provides to an orchard.

Artists and some of the public have signed on with the scientists to be bellwethers. Now used to being ignored, denied, distracted, and argued into a silent, frustrating rage, our existence depends on who prevails in negotiations with powerful immoral lawyers, and financially motivated rainmakers. We cannot hope to convince the deniers of truth but insist reason prevails.

Rainforest destruction again rose to attention as a global issue recently during an interview at the Environmental Impact II exhibition in St Petersburg, FL. Fox News was reporting massive forest fires burning in Brazil and at the same time, destructive fires were burning all over the Western US, annihilating neighborhoods, businesses, and acreage. I was asked on-camera by the TV interviewer when I began doing my series of paintings. I answered, “In 1996, after filming a documentary for the Discovery Channel on the status of the forests in the Amazon”. He seemed visibly shocked that this same critical question in 1996, we are still debating in 2019. I fully agreed. For me, it was a pivotal moment as an artist. We are now just 20 years worse off.

The nurturing of Greta Thunberg’s generation for the future of the diversity of life on the planet depends on the current choices made by everyone – every day – continually. The new paradigm shift for 2020 is ‘being silent is synonymous with complicit’. This applies to a broader scope of pressing subjects than just the natural environment. Adopting the Earth Charter https://earthcharter.org/read-the-earth-charter/preamble/ globally would be a really good place to start. The ‘world equation’ is measured by how we conserve, and by what we preserve, and how we share the resources. Preserving ecosystems must become the most important priority, rather than the dominance and power of the few. Recognizing the human impact on ecosystems demands we admit we live in an interdependent world, and act accordingly. We need a hands-off-policy on things that sustain a livable global future. We must keep the subject of diversity versus destruction on top of the global priority list as a ‘shared investment’.

As human populations expand, wild-nature grows smaller and less able to sustain itself. We ‘nibble’ at the edges of these ecosystems filled with indigenous people, animals, and masses of intact diversity. Where do the millions of creatures in life’s astounding diversity flee? Their existence depends on those un-accountable, self-serving bullies who plunder with little mercy. Humans may in fact destroy paradise, and even with the best ‘Tech’, it will not be easily re-created.

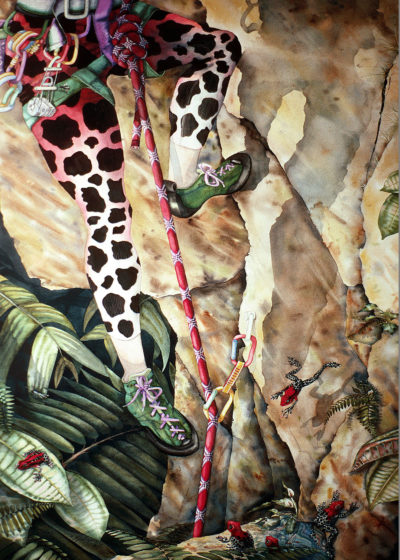

Modern humans are compelled to go everywhere. We want to build airplanes, rockets, ships, cars, ride bikes, to fly like a kite, or mimic nature by climbing with ropes, clamps, and pins to defy gravity, using nature as a playground. Conquering ‘where no man has gone before’ is a primal human urge, but also an addiction. Artists can present a window for us to view our foolery. Our tendency is to crowd out all other creatures and dominate the wilderness. But do we have a clue what we do when we get up there? ‘Here it comes again’ is painted from the frog’s point of view, asking, ‘what on earth is it?’ Maybe with the advent of virtual reality, we can experience the thrill of domination virtually, which will be a big relief to the frogs, lizards, and birds.

When I started out painting this collection of environmentally conscious work about human interactions with nature, I was working with individuals who dedicated their lives to making the world a better place. I wanted to be a part of that movement. To be dedicated to doing the hard, messy work of preserving indigenous people, rare and endangered species, even at great expense and personal cost. We had tremendous hope that if we put our backs into it, made the time and money, and collectively headed in the direction to save humanity from a path of destruction, we had no doubt we could succeed. We did, for a time. We trusted that those in positions of power only needed reliable information, and then they would make the necessary adjustments to correct the miss-guided.

We trusted those navigating the global ship because we shared the same goal of protecting humanity from calamity. Half a century later, those drunk with too much power and self-interest, have undermined the foundation we built and proven they will sacrifice the future of humanity at the altar of greed.

It has been incredibly difficult, and a bit life-shattering, to be asked to write about my objectives when I first began creating my art, because I have realized with the help of the Covid-19 pandemic, there are those still less evolved who will not place a piece of cloth over their mouth for the benefit of their neighbor. And they are in charge and have an agenda only for personal power and gain. We have fallen further behind than I ever thought possible. Reading the Earth Charter I signed back in the ‘90s, I wonder, are humans just incapable of global cooperation? If this is so, humanity is doomed to be destroyed by the petty, narcissistic, and self-serving. And there are no ‘better angels’, like my many friends who died while conserving the natural world.

I cheer on my fellow artists in this exhibit who are championing banning the use of single-use plastic and cleaning the oceans and more. I know that long after I am dead, when they take a core sample of the earth, our generation will be known as the fossil fuel-plastics generation on the planet.

Working with friends, family, employees and biologists, botanists, and field researchers from all over the world, our lives contributed to saving hundreds of thousands of plants, birds, animals, and thousands of miles of forests. All our voices should be as clear and passionately devoted as the Greta Thunberg’s. Sadly, our time, when held up to the light of the historical perspective, will be duly noted in history as the first global human pandemic, the rise of oligarchs, the advent of plastic at the very core of the ecosystem, and the launch of SpaceX, designed to give us an exit plan to Mars when we thoroughly trash this planet.

What little hope for the environment I can dredge up, has been withered by current circumstances has beat optimism right out of me. But if we can redirect our attention from live streaming social media and chaos of current affairs long enough to address the bigger picture, here is my ‘ray of hope’. It is back to square ‘two’ (I am an optimist at heart). I learned life’s secret to achieving any successful endeavor is to first relate the task to something familiar, especially on a personal level. The artists, family, friends, and even strangers, instantly know where I stand on. ‘We all are nature’. No avoiding it. Primal urges like greed, survival, and power have their place when needed to save your life. But if we are going to survive as a species, this urge needs to kick in to save (serve) the whole planet. There are no trees on Mars. Humans need to learn how to better prioritize urges on every level. Every talent, avocation, skill, and need can manifest in a fair and just future. Resign our primal impulse to pillage and plunder to history and leave it there. Living things have autonomy. Sentient beings can make the emotional investment to engage at the table of compromise and to work toward the objective of global sustainability and the greater good. Trust me, humanity is brilliant and most of compassionate nature. We can do much better than this.

MARY HELSAPLE lives in Sedona, Arizona with design engineer Neal Williams. Teaching studio painting and watercolor class at the local community college, she has completed ‘Physics of Watercolor’ instruction on the technique in watercolor, a ‘Wetland Wildlife, field sketch journal’. She is working on several other small books, An Artist Guide to Nature Journaling, and an illustrated travel log called ‘A Hat for the Rainforest’, and a short story of a wren called, Mr. Stubs Magnificent Tail’. With her fine art paintings depicting desert wildlife to rainforests, Helsaple continues to advocate preserving the natural world for future generations while focusing on creating a small footprint and ‘living in equilibrium’ with all the critters that find her abundant home habitat. www.helsaple.com

This blog is part of MAHB’s ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT II series, a travelling museum’s exhibition.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.