Art on Impact

I started this essay in fall 2019, months before the COVID plague dropped its dark filter between us and our view of the world. It’s too early to write from a post-COVID perch; and too late to get solace from what was true for sure before Wuhan. What we probably all agree on is this: we turn to art instinctively, all kinds of it, to help steady the unsteady ground at our feet.

Storytellers from Spike Lee back to Sophocles give us plenty to work with–if their purpose is to describe the human predicament. Artists over centuries have been generous in leaving a legacy of detailed cautionary pictures and unambiguous lessons. If art were truly transformative, Tintoretto’s great St. Roch Healing the Plague-Stricken, Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, and O’Sullivan’s photos from Gettysburg, and Dickens’ vignettes of London would have worked their magic by now. They haven’t. Any of these masters, transported to 2020, could pick up where he left off, painting or photographing or writing–fully occupied for decades by fresh bleak subject matter.

Poets and muralists, we photographers, painters, sculptors, and all the rest are part of the triage team rushing to the rescue. We do it–make art–because our humanity demands it. But if art had the power to heal, to veer humanity away from catastrophic habits, our world by now would be a sylvan tableau, not a teeming diorama fraught with chaos. Assaults against nature would be unthinkable and genocidal war an archaic relic. In a world enlightened by art, mention of “Vietnam” would more likely conjure thoughts of exquisite coffee and sublime cuisine than of atrocity, napalm, and impossible atonement. “Glacial calving” would suggest only the raw beauty of one of nature’s glorious moments, not the gut-wrenching image of starving polar bears drowning in a warm rising sea.

War photographers, poets, political journalists, and artists have in common brash altruism. And we who value their work want to believe that the world needs them–that it is somehow a better place because of their commitment to showing us what they see. Of these examples, I best understand the visual artists, since I earn my keep by making pictures–photographs of industrial landscape, architecture, dams, launch pads, and archeological sites.

We artists tap a bulging vein of sentimental guilt. Pictures of slabs of Manhattan-size ice shelves, drifting north to the tropics, scream from websites and gallery walls everywhere. On network TV, doe-eyed seals suffocating in coats of slimy petrol invoke us to buy implausibly gentle dish detergent (easy on your hands; tough on grease). At their core, none of these campaigns by artists and media hucksters is bad. But neither is any of them useful. From Art’s Bully Pulpit paintings, and especially photographs “about the environment” drone a redundant drone: “You are to blame; everyone is an irresponsible carbon-hog; art is the map guiding us to redemption.” When we artists scold, we are ineloquent. When we harp we are wearisome. In the ensuing commotion, the first casualties are beauty and visual subtlety.

In these matters I’ve always felt like an outsider, never comfortable in the sometimes-smothering embrace of “environmental” artists. I know of none who is not earnest. But their lockstep to a monophonic anthem, marching toward utopia or away from doom’s brink, is depressing and–for its numbing simplicity–an embarrassment. With most art, that misfire is not intentional. Nor is the faintness of the barely audible ping of its impact on the world.

The best art reminds us of what we already know. Like a gifted math teacher whose elated first-grade student sees 2+2 = 4 as a brilliant personal discovery (and rightly so), the best artists give us revelation wrapped in plain language. Think of anything by Maya Lin or Andy Goldsworthy. Thanks to their fluency in mud and sticks and stone, they speak a language written in glyphs we were born understanding. Their work shows clearly the redundancy in “environmental” “art”. The beauty in their work owes, simply, to its unabashed beauty. Versus Cristo’s draped coastline or wrapped Reichstag, or De Maria’s Lightning Field, or Lita Albuquerque’s giant blue balls flown by Air Force cargo plane to–then strewn over–Antarctica. This work all shrieks the ego of the artist. Lin and Goldsworthy, cool-headed, tread soft, laying out the urgency of our predicament by quietly showing us what we miss in the frenzy. They ignite conversation, personal engaging conversation. We know from other sages–Laurence Olivier to Yoda–that the most compelling voice is the one we must lean into. No one would dispute that the whisper is more seductive than the shout.

We who took art school seriously believed that our unique vision benefits the world (which obviously anticipates our next insight) and that our special gift matters. We were anointed to “make a difference”–a noble-seeming goal. Other than sprouting generations of narcissists, not much good or ill has come of decades of us snorting this line. But neither have we produced much notable art–lucid work that adds to the rich literature of ideas. We have succeeded in making things that resemble good art. That is good enough, mostly. But the absence of incompetence is not brilliance.

We are choking on issue-driven art by concerned ethical colleagues. But an echo chamber is a dull venue. Today’s audience for “art with a message” is the audience that already gets it. People who go to exhibitions “about the environment” already recycle their Starbucks cups and wear biodegradable clogs. The gallerist or artist who drives a 4000 lb. SUV to an opening climbs out of it onto pretty wobbly moral ground.

Moving Pictures

As a photographer, I can speak most credibly about pictures, photographs. I’m not among the number of my cohort who hears alarms clanging, hyperventilating in front of huge prints of Greenland glaciers melting or of wild-fire-ravaged Sonoma County vineyards smoldering. My response is, I believe, more appropriate. I wonder (out loud sometimes, to my embarrassment) why anyone would make one more picture like this. Then I drill–truly curiously–into how such focused zealous work can deliver photographs so lifeless. The answer is not elusive, not mysterious, or far-fetched.

Uninspired pictures ring dull because they are aimless. Not useless but aimless; they meander over well-trod territory blazing no new path toward no clear point. One photo of a bobbing thousand-acre ocean island of plastic bottles and soda straws is as descriptive as the next and perfectly serves journalism or YouTube. But a picture simply “of a horror”–at this stage in the life of 21st-century art–is a waste of my time and yours. Outrage-fatigue sets in way before the end of the photo essay, or the museum show or the PBS exposé.

There is no excuse for recycled art about ecological horror. Whether a slide lecture on micro-polymers in the food chain or a photo essay on shrinking Grizzly habitat–we need no more of any of it. The clutter and noise of it all is its own kind of pollution–or at least high-minded irritation. Yet nothing keeps us ambulance-chasing photographers from pouncing enthusiastically on news of the next global crisis. As social creatures, we are drawn to what matters to us, and we are smart to study what threatens us.

Good pictures are moving. They may be both kinetic and jolting. The title Environmental Impact shows the virtues–and the limits–of written English. Impact is memorable, like a video of Mount Saint Helens erupting, or scratchy footage of Hiroshima vaporizing. But “environmental” is a tired word, its five syllables threadbare, almost meaningless now, exhausted–less powerful than if its space were left blank.

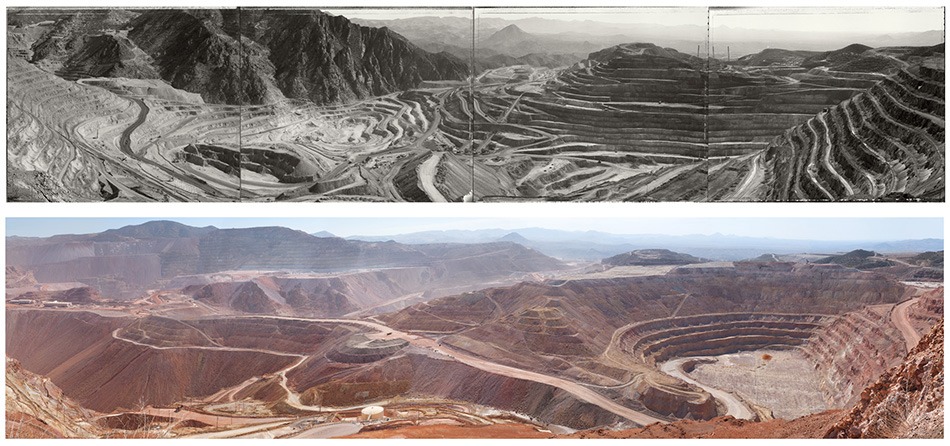

Nature magazines and zealous artists’ websites instruct with photographs of snowcaps shrinking, of ravenous ferrets decimating waddles of penguins, of saltwater lapping at Venetian frescos. These images are hashtags, shorthand for what should urgently alarm us. There are too many of these images to act on; too many artists begging for our empathy. Their good works add up to a tragic chronicle, a litany of our sins; but they cannot, for their sheer volume, amount to impactful art. No one will argue, for example, that Ed Burtynsky’s “environmental” photos are not useful; or that his pictures are not memorable (close your eyes now and you can conjure at least a few of them). But their message has the subtlety of a manifesto yowled through a megaphone. The pictures elevate adrenaline, not consciousness. They corroborate the data: we are screw-ups and doomed. What they show us we already suspect.

A few years ago at a packed university symposium on the state of contemporary creative photography, the keynote speaker (a revered photo elder and professor), at the podium basking in the adulation of a packed auditorium (colleagues, students, former students, patrons, collectors) declared to the soon-to-be-gob-smacked crowd: “Photographers–there are just too damned many of you”. That the planet is overrun with photographers is an old idea. A celebrity photographer, saying out loud in public that we are mostly redundant, jolted me out of the lonely notion that I was the only person who thinks this. But the idea is wrong. There are not too many photographers, any more than there are too many poets or architects or painters. It is simply that almost nothing we do is game-changing; almost none of it matters to anyone but us and our friends. We photographers are the extreme case since we are obscenely prolific. But in the business of saving the world, painters, sculptors, poets move the needle just as imperceptibly.

Here a dose of humility comes in handy, and it can be a potent remedy. What ails the planet will eventually be set right by a full-out pandemic or asteroid-induced mass extinction. Until then, we are stuck with the tools we have, and with one another. Art can help, but only as homeopathy. To give it more credit than that is naïve. Like medicine, art can heal only what it can reach. So our best hope is not hope, but behavior: habits scaled to our place in the scheme; consumption scaled to conscience; generosity scaled to the need around us–all around us, not just in plain sight.

Recently I attended an environmental symposium on the decimation of biological diversity along a thousand-mile swath of the US-Mexico border. My colleagues presented powerpoints showing the many ways in which they, as concerned artists, scholars, and scientists, engage with the natural world in crisis. It was the usually packed room, a projector, a screen, a soundcheck, introductions, then “talks”; I sat in the back, watching the hundred heads in the ten rows in front of me nod in sync, sympathetic to the scores of horrors suffered by Indigenous families, gray wolves, big cats, herds of desert-dwelling beasts. A half-hour into the evening, as if skull-whacked by a skillet in a goofy cartoon, it hit me – the words, the language of our earnest presenters, hung on the most dangerous of fundamental propositions. Them, they. “They” are building a border wall; “They” are destroying habitat. None of “them” understands or respects ecosystems. “Us” and “we”, if mentioned at all, put us, righteous scholars and artists, on the side of God and the animals.

A Recipe

Speaking of ecology, making a difference is the least useful of human ambitions and costs the most. Since the Industrial Revolution, us making a difference has left the planet, the natural world, in a serious pickle. If you don’t believe it, ask the earth, the sea, the stratosphere.

I offer these thoughts: If there are already a thousand pictures of open-pit mines, why make more? If a hundred artists have already flown to the arctic to witness catastrophe-in-the-making, why would one more planeload help? If you have seen a dozen videos describing data on sea-ice loss, what does one more teach you? The best response to any of these impulses is emphatic inaction. STAY HOME. Do as little as possible; try ardently to not make a difference. Sell what you do not need. Volunteer to teach kids to read; learn gardening; lose 20 pounds; quit Facebook; drink more water; walk; register to vote and spread the word; eat fewer animals; dress elegantly; write rather than text; befriend rather than friend; savor instead of like; at least once pay for a good massage; study a new language. If you are a painter paint; a photographer, photograph – but less and better. Trust risk; risk trust. Do no harm. And marvel at a world beginning to heal.

Martin Stupich is a professional photographer whose primary subjects include cultural and industrial landscapes across the United States and Asia, often focusing on the desert western frontier. He received a Master in Visual Arts from Georgia State University in 1978.

Martin Stupich is a professional photographer whose primary subjects include cultural and industrial landscapes across the United States and Asia, often focusing on the desert western frontier. He received a Master in Visual Arts from Georgia State University in 1978.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.