It’s about 18 months now until the Paris climate showdown.

The good news is that there’s quite a lot happening. The clarifying science, for example, is no longer easily denigrated. The IPCC’s 2°C carbon budgets, the new age of “extreme weather,” the fate of the Arctic, these can no longer be cast as fervid speculations. Denialism – at least classic denialism – has peaked. This is a time of consequences, and we all know it.

But what about Paris? Why do I even mention the international climate negotiations? Don’t we all know that the North/South divide is unbridgeable? Don’t we all know that the wealthy world will never provide the finance and technology support that’s needed to drive deep and rapid decarbonization in the emerging economies? Don’t we all know that the prospect for a meaningful breakthrough in the climate talks is nil?

In fact, we do not.

Step back for a moment, and admit that we are not yet doomed.

For one thing, the cost of renewables is plummeting, even as their performance rapidly improves and new technologies come online. Which is to say that we really do have a chance to stabilize the climate system. The bad news is only that we’re lot likely to do so in a business-as-usual world. That is, the normal dynamics of market commercialization will not suffice to revolutionize the global energy economy and solve the climate problem. All major energy forecasts – even the most technologically optimistic– agree that much more will be needed to yield the “radical” emissions reductions. It has gotten to the point that even scientists, trained in reticence though they may be, are increasingly calling for emergency mobilization.

The real problem is that the remaining carbon budgets are so small, and time so very short, and the fossil-cartel so powerful, and the need for low-carbon investment so pressing, that market/technology dynamics will not alone drive the necessary progress, at anything like the necessary speed. Any sufficiently rapid climate transition will of course seek to leverage these dynamics, but it will also demand the concerted and coordinated efforts of a large number of countries, and these countries must somehow agree to focus their financial and technological resources on investment programs that are designed to further the common goal of extremely rapid emissions reductions.

This is a very tall order, but it can be met. But only if each nation sees the others to be doing their fair share in the common effort to rise to the climate challenge.

If countries don’t see this equitable common effort, if each rather sees the others to be making efforts that fall far short of their fair shares, then they will be hard pressed to do better, even if they wish. They will find it pointless and even self-defeating to step forward with the extremely ambitious actions that are now necessary. This is simply the nature of the case, which is to say the nature of climate as a global commons problem, and the reason why “the equity issue” will never go away, and – barring a breakthrough – why Paris could well be another train wreck.

In fact, Paris could be worse than Copenhagen. Nor does the danger just include further delays, or more dispiriting blows to the multilateral process. We could easily find ourselves, in just a few years, trapped in a global race to the bottom, one in which mutually-reinforcing patterns of free-riding have become the established norm, and all attempts at coordinated mitigation amount to little but rhetoric.

But this is not our fate. There is an alternative, and it is, simply, cooperation. Robust global cooperation of a kind that can endure even under the extremely challenging circumstances that are in our future. Cooperation of a kind that is can only be held together by the confidence that all countries, or most all, are doing their level best to do their fair share. If such a confidence can take root – if a shared commitment to climate equity can be added to the disruptive potential of the emerging renewables revolution – then there is hope.

But to realize this hope, a substantive global climate equity debate will be needed, and it will have to move far beyond lose talk and rhetoric. In fact, it will have to become focused enough to provide quantitative guidance on the appropriate scale of national “fair shares” in the common global effort. For even in the post-Copenhagen world of “bottom up” pledges (now formally called “Nationally Determined Contributions”), fair shares still matter. In fact, they matter more than ever. Countries will be making “intended contributions” that are calibrated to their sense of whether other countries’ contributions are fair, or at least fair enough. This is simply a fact.

The key, again, is that each nation must see the others to be doing their fair share in the common effort. To that end, we critically need a coherent and widely accepted framework that translates the U.N. Framework Convention’s core ethical principles – responsibility and capability on the one side, and equitable access to sustainable development on the other – into at least approximate guidance on national fair shares. Such guidance could help set expectations in advance of the upcoming round of national pledges, and motivate public actors around the world to make well articulated, clearly justified demands of their governments. It could provide a standard against which countries are expected to defend their pledges as appropriately ambitious and fair. It could empower Parties and civil society to critically review those pledges as they emerge, and to recognize leaders and call out laggards. It could pressure less-ambitious Parties to ratchet up the ambition of weak pledges, and to bring the pledges as a group into closer alignment with the requirements of climate protection (in scientific terms) and with each other (in equity terms).

This isn’t the place for a long review of the climate equity debate, as it’s evolving within the formal climate negotiations and the global civil society networks that have crystalized around them. But there are some bases that you might want to touch, if you want to get up to speed on this debate, and on civil-society strategy. One bit of essential reading is the Climate Action Network’s painfully-negotiated paper on equity indicators, which was published in last September. Another is this page, on the Greenhouse Development Rights site, which introduces the Climate Equity Reference Calculator and its sidekick, the Climate Equity Pledge Scorecard.

The strategy behind the Climate Equity Calculator needs a name, and for lack of a better let’s call it “the Equity Reference Framework strategy,” which has unfortunately been contracted to “the ERF.”

The ERF strategy comes, in the end, to radical transparency. The goal is to make the national pledges comprehensible, relative to the remaining carbon budgets, and at the same time to make them comparable to each other, in terms of straightforward, indicator-based quantifications of the Convention’s core equity principles.

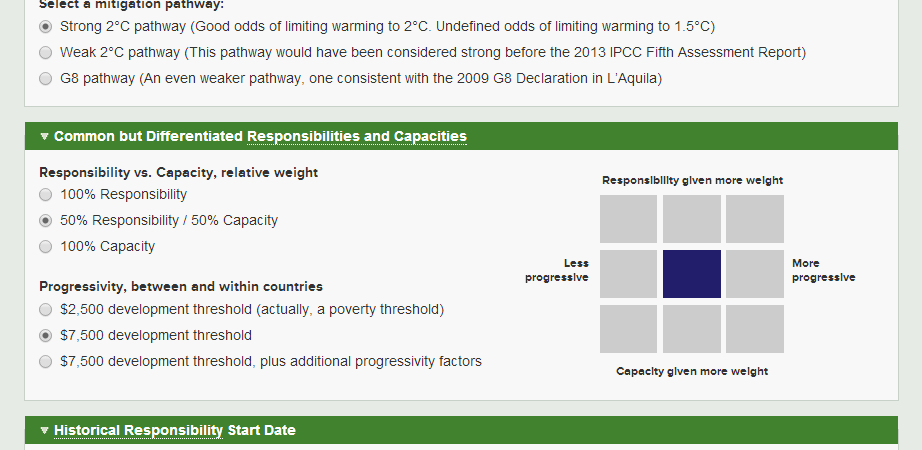

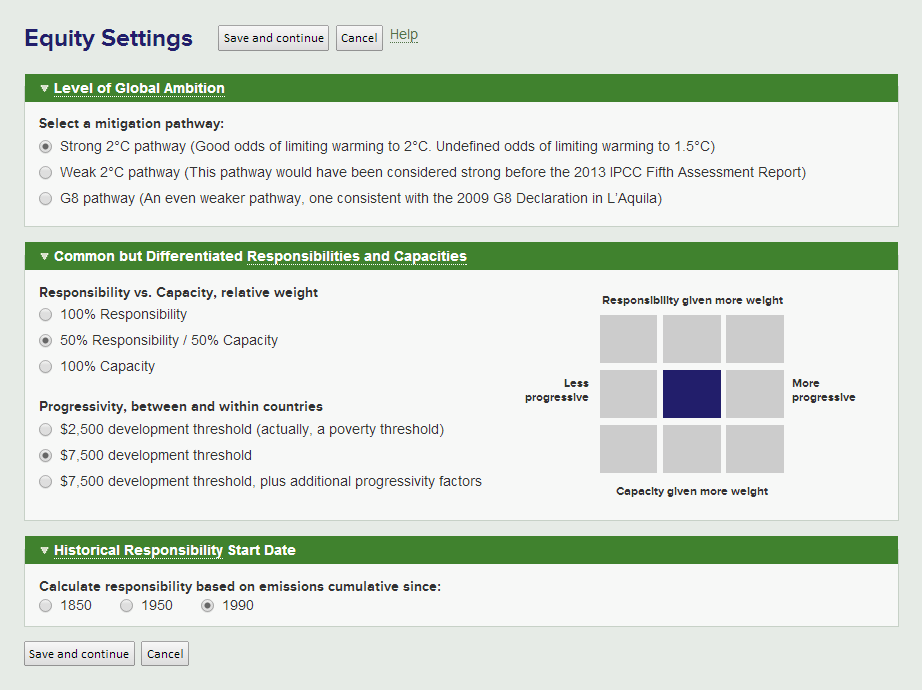

For example, in the Climate Equity Calculator, we lay out a set of reference mitigation pathways, which are carefully positioned in relation to the IPCC’s 2°C carbon budgets. But it’s up to the user to decide if they want to run the numbers against a “Strong 2°C pathway,” a “Weak 2°C” pathway, or a (very weak) “G8 pathway.”

Similarly, it’s up to users to define their own preferred settings for the all-important “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” that are at the core of so much (often unproductive) debate. Once they’ve done so, their specifications are used to define a “responsibility and capacity index,” which in turn is used to determine each country’s fair share of the global mitigation effort, as specified by the chosen mitigation pathway. As for the political conclusions that users might draw from the Calculator’s indicative estimates of fair shares (which can be rather challenging) these are another matter.

The user’s options are quite flexible (see the “Equity Settings” panel) and we intend to make them more flexible in the future. Our plan is to support a very wide range of plausible approaches to the Convention’s core equity principles.

The Climate Equity Pledge Scorecard, for its part, is deigned to quickly assess a country’s pledge. It is based on the Calculator, and it similarly begins its dialog with the user by asking them to choose a preferred global mitigation pathway, and a preferred set of equity settings. It shares these settings with the Calculator, but it can also be used on its own, for example in settings where users (or presenters) might want to be confronted with fewer selections and less detail. The bottom line here is that the Scorecard’s user interface allows all the core “Equity Settings” to be changed, but for the full range of settings (for example, if you want to switch from production-based to consumption-based emissions accounting) you need to go to the Calculator.

There’s much more that will be done to make these tools yet more general, more usable, and more useful to civil society and to Parties, though we’ll need more funding to do it. In the meanwhile, we look forward to feedback, and we want to stress these tools are, we believe, already able in their present state to support a robust debate on global climate equity, one that focuses and clarifies the discussion of fair effort sharing and the assessment of national pledges.

So take a look. About the Calculator and Scorecard is probably the best place to start. Both tools contain good help systems, and note also that there is a decent quick guide, which provides a basic tour and points out many key issues. There’s also a great deal of detailed technical documentation for those who want it.

In hope, Tom Athanasiou

Tom Athanasiou is the Executive Director of EcoEquity and can be contacted via email at toma@ecoequity.org

MAHB-UTS Blogs are a joint venture between the University of Technology Sydney and the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to joan@mahbonline.org

MAHB Blog: https://mahb.stanford.edu/blog/the-road-to-paris/

The views and opinions expressed through the MAHB Website are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the MAHB. The MAHB aims to share a range of perspectives and welcomes the discussions that they prompt.