Marianne Bickett, Wolf Collage I (detail), papers, tempera paint, 2009, © 2021 Marianne Bickett

Twenty years ago, I volunteered for a week at Wolf Haven International in Tenino, Washington during the summer off from teaching. To this day, I will never forget standing in the center of the sanctuary and hearing the wolves howling around me.

To this day, I will never forget standing in the center of the sanctuary and hearing the wolves howling around me. It breaks my heart to think of a world bereft of these essential beings. A world absent of the howl of the wolf would be a doomed world. Wolves have long been understood to be a keystone species; one that, because of its place in the food chain, aligns all other creatures in its territory into a healthy state of biodiversity. Yet, the perception of the wolf in many areas is one of the villain and their existence demonized.

Wolves were here in North America and in Europe, where they are still hunted, long before humans arrived. The symbiotic relationship between humans and wolves flows far back into our shared primal history. Indigenous peoples the world over revered and feared the wolf with respect, imbuing it with a place of honor and emulating the wolf’s many positive attributes. To this day, American Indians, for example, still embrace the wolf and its essential niche in a world that misunderstands them. And today, there is living proof of the wolf’s importance. Case in point, let’s look at the situation in Yellowstone.

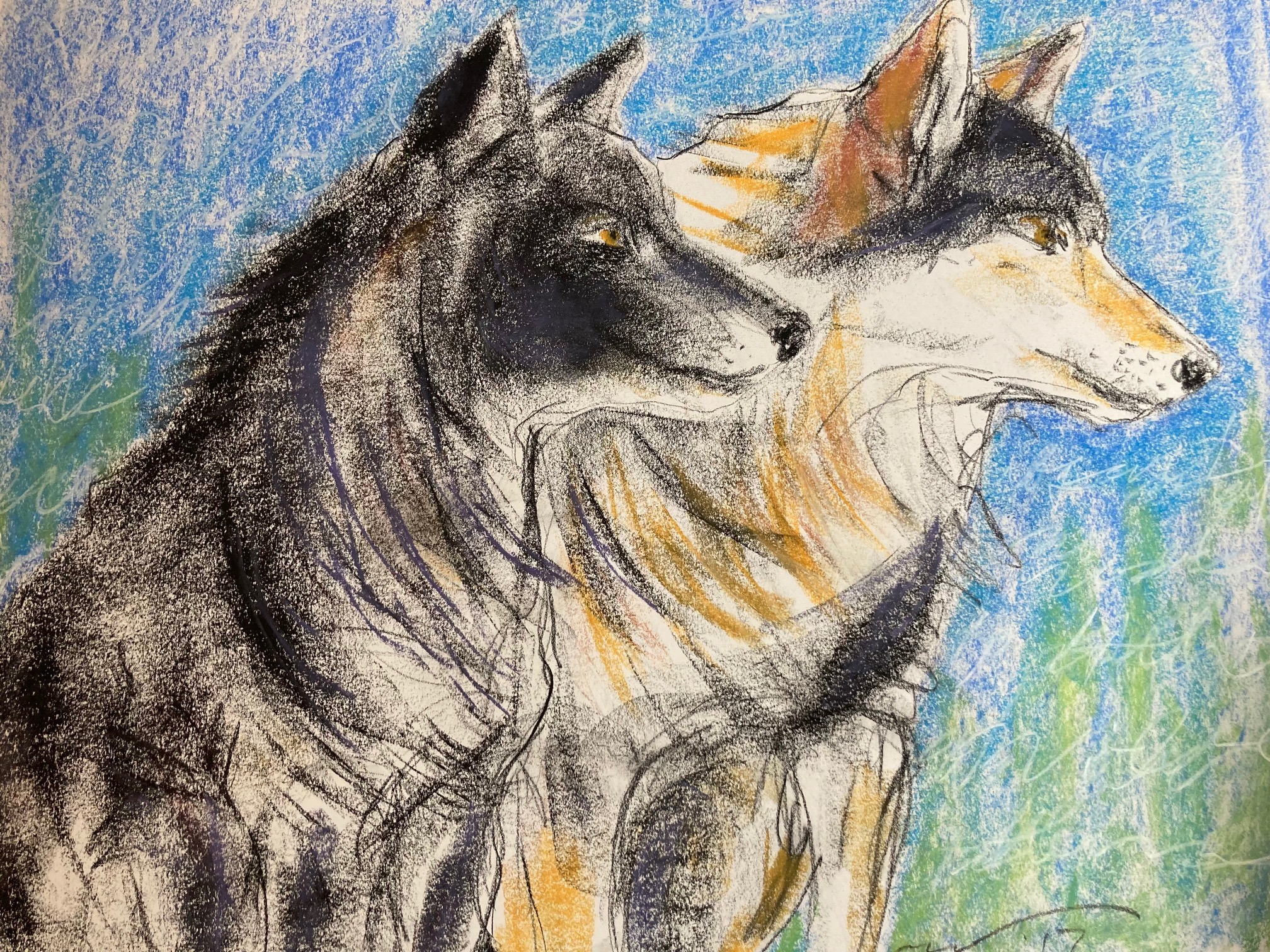

Marianne Bickett

Gazing Wolves

charcoal/chalk pastels, 2009

© 2021 Marianne Bickett

Since 1995 the grey wolf has once again inhabited the wilds of Yellowstone. During the recent years that the wolves have thrived there, amazing changes have taken place in terms of not only the animals, but the landscape as well. Because prior to 1994, after wolves were killed off in Yellowstone for 70 years, the ecosystem began to deteriorate. Elk, who are among the wolves’ favorite prey, began to increase in numbers and decimate the willow, aspen, and cottonwood trees near rivers and streams due to their winter feeding. This affected the beavers, who had nothing to build dams with. In 1995, there was only one beaver colony in Yellowstone.

Wolves kept the elk from staying in one place, so when the wolves were reintroduced, the trees began to flourish again, as did the beaver. It is noted that the willow tree has regained its health and is doing very well, thanks to the wolves. And, today, there are over nine beaver colonies and there are surely more to come as the wolves keep having a positive effect on the biodiversity of Yellowstone. “Beaver dams have multiple effects on stream hydrology. They even out the seasonal pulses of run off; store water for recharging the water table; and provide cold, shaded water for fish while the now robust willow stands provide habitat for songbirds.” (Quote from Yellowstone Park source listed at the end of this article). And the scavengers have benefitted from the wolf kills during the winter, whereas, in the absence of wolves, they had to rely on less frequent snow kills (depth of snow killing elk and deer). Biologists have even verified the tales of Indians regarding ravens following wolves and leading them to prey. Their symbiotic relationship is yet another example of how, when the wild is left to its own, the web of life is intricate, indeed. It is when humans decide to interfere that the environment and animals suffer. Without a doubt, wolves are what they call a true food distributor.

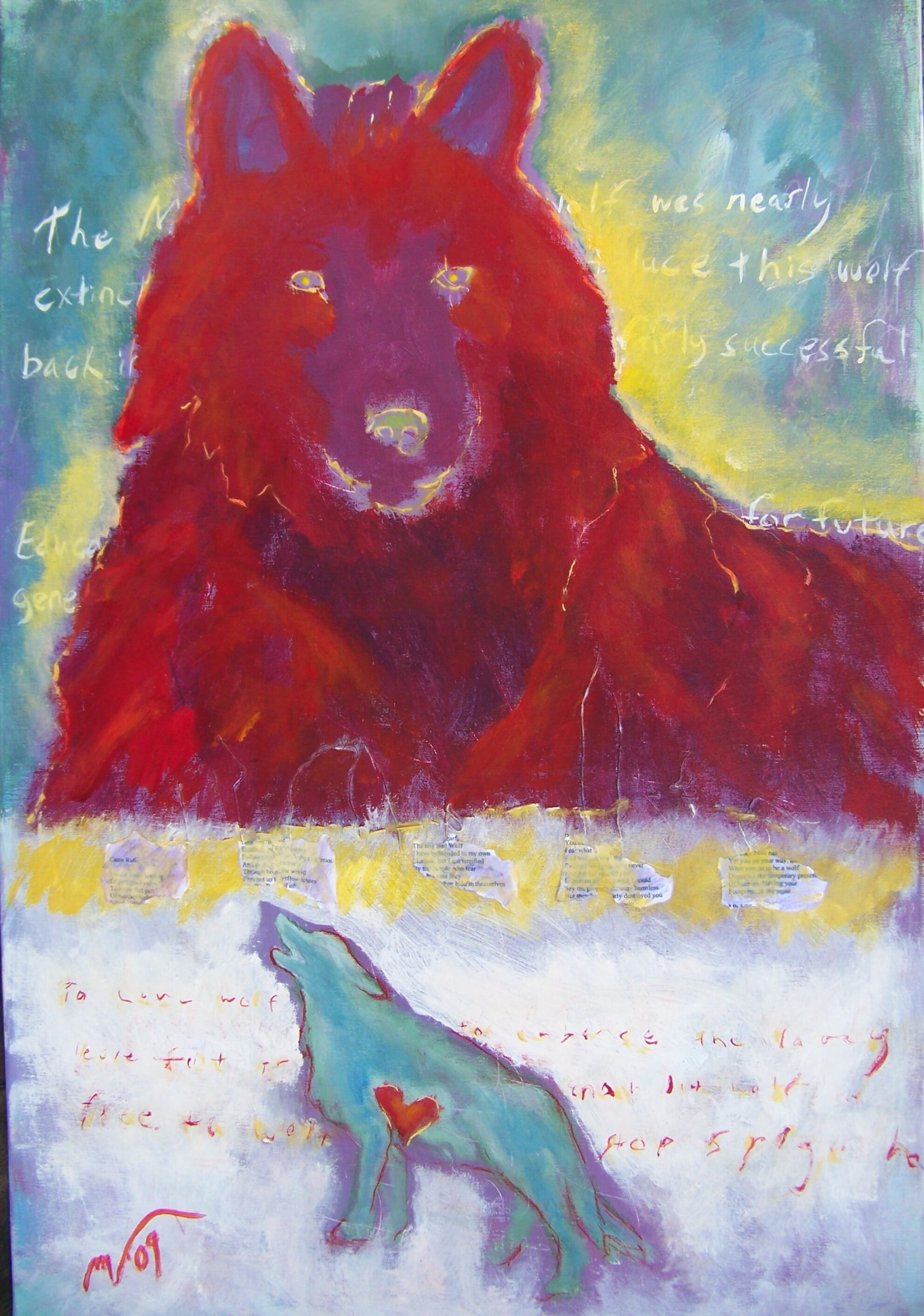

Marianne Bickett

For the Wolves: Canis Lupus

acrylic mix-media, 2009

© 2021 Marianne Bickett

So why do people hate wolves? The disparity between wolves and humans goes far back in time as does our interdependence on them. Wolves howled at night and invoked fear and stories of demons. The notion of the werewolf may have begun among some of the native people in North America. It was taboo to wear a pelt of a wolf because it could turn you into a wolf/man and that was unacceptable and would result in exile. The myth of the big, bad wolf of European origins has been so entwined in our psyches for so long, people seem to forget the facts of the wolf’s critical role in nature and instead cling to the hate.

In Wisconsin, as another example of how wolves benefit humans and other animals, wolves have reduced the number of deer road kills dramatically by keeping deer from being hit due to their movement patterns. There are a few wolf road kills but the number is low. In that state, as well as other states and countries, the benefits of the wolf’s presence far outweigh any problems. Ranchers are reimbursed by the government for proven wolf-kills on their herds. Defenders of Wildlife instigated anti wolf depredation programs by working with ranchers in Montana and other states across the west in terms of how best to protect their cattle in non-lethal ways. By educating ranchers how to live peacefully next to wolves and by offering viable alternatives with resources, Defenders have made a huge difference in helping to protect wolf populations. They also work tirelessly with legislation and in courts.

Marianne Bickett

Wolf Collage I

papers, tempera paint, 2009

© 2021 Marianne Bickett

Throughout American Indian mythology in North America wolves were admired for their devotion to the family. Concepts of the Alpha leaders and how the pack helps rear the young, influenced cooperation within the tribe. And the wolves’ fierce protective instincts and adept hunting skills also inspired humans, enhancing survival in often harsh climates. The Pawnee of Nebraska had a very close relationship with wolves. Known as the Wolf People by other tribes, even their hand signal representing “human” also meant “wolf.” Other tribes such as the Blackfoot, like the Pawnee, looked to the heavens and saw the journey of the wolf in the stars, watching Sirius (Wolf Star or also known as the Dog Star) move in sync with the seasons across the night skies.

The Ojibwe of the east coast believed that God took the form of wolves. Wolves were considered to be guardians of humans through life and death. Among the Oglala Lakota people there was an elite Wolf Society composed of highly skilled warriors who observed wolf behaviors and hunted in a fashion much like the four-legged Canis lupus. The Wolf Society members were permitted to don wolf hides as an act of courage and honor, praying to the spirit of the wolf before a hunt. In a similar yet different way, Amorak is a name given by the Inuit people for wolf or wolf spirit. Amorak was embodied as a wolf leader who taught the people about hunting and would devour the reckless ones who ventured out alone at night to hunt. The Incas considered both dogs and wolves to be holy. In many nations and tribes wolves were held in high regard and had mystical powers. If it had not been for that first wolf-human relationship, dogs never would have evolved from the wolf. Where would we be without our domestic canine family members?

We owe a great deal to wolves, and the recent despicable slaughters in Oregon, Montana, Wisconsin, Washington, and other states are a kind of insanity I cannot wrap my head nor heart around. I grew up fascinated by wolves and have cherished their dignity, tenacity, strength, and persistence. Wolves, like other top predators, go after the young, weakened, and older animals. They keep wild herds healthy and strong. We need to keep addressing misguided perceptions about wolves and supporting those who are working hard to help them. Please write your legislators and donate when you can to Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Biodiversity. The time is upon us to care and to act.

Marianne Bickett

Red Wolf: Canius Rufus

acrylic mix-media, 2009

© 2021 Marianne Bickett

The facts for this article were obtained from the following sources as well as the author’s previous research about wolves.

Two excellent books:

In the Company of Wolves by Peter Steinhart

Wolf by Garry Marvin

Information about Defenders of Wildlife work with Ranchers.

Websites where I gathered information regarding Native American Spirituality and Wolves:

Wolf Song of Alaska

American Wolves

AAA Native Arts

War Path to Peace Pipes

There are many wolf sanctuaries around the world, such as Wolf Haven in Washington State.

Marianne Rose Bickett is a retired teacher, who expresses her love of nature through writing, and art. With a Master’s degree in Art Education, University of Illinois, 1986, Marianne has utilized her expertise as well as enjoyed being a life-long learner.

Marianne Rose Bickett is a retired teacher, who expresses her love of nature through writing, and art. With a Master’s degree in Art Education, University of Illinois, 1986, Marianne has utilized her expertise as well as enjoyed being a life-long learner.

Books: Fiction: the Art á la Cart trilogy: Leonardo and the Magic Art Cart; Art Rocks with Ms. Fitt, and The Present, Kala’s Song for Young Adult through Adult.

Non-fiction: Art á la Cart, Memoir of a Teacher, A Special Creek, Enrichment, and Magic.

Marianne taught everything from special education to art, from preschool through college, for nearly forty years. Teaching in mostly public schools, as well as an art museum, Marianne’s vast experiences across the country have given her a rich history from which to draw upon for inspiration in her books.

Throughout her career, Marianne was devoted to the environment and creating opportunities for her students to draw inspiration from their inner and outer worlds. For example, greatly inspired by the works of Andy Goldsworthy, she embarked upon utilizing a creek adoption to engage her curious charges in ephemeral creations. Across the curriculum projects that involved math, science, music, literature, and art, as well a multi-sensory approach, were the mainstay of Marianne’s approach to teaching.

Married to composer Brian Belét, Marianne cherishes her family that includes her son, Jacques, his wife Irish, and two young grandchildren. Marianne continues to share her joy of life on Instagram, newsletters, and occasional workshops and classes. Her many interests include meditation, yoga, long walks, and advocating for the environment and for animal welfare. Marianne enjoys time with her sister, Jane, on her Begin Again Ranch, caring for all creatures great and small.

Photo: Author and Artist Marianne Bickett photographed in Tualatin River National Wildlife Reserve, Oregon, by Earthdarling Portraits of Sherwood, Oregon.

This article is part of the MAHB Arts Community‘s “More About the Arts and the Anthropocene”. If you are an artist interested in sharing your thoughts and artwork, as it relates to the topic, please send a message to Michele Guieu, Eco-Artist and MAHB Arts Community coordinator: michele@mahbonline.org.

Thank you. ~