Item Link: Access the Resource

File: Download

Date of Publication: September 26

Year of Publication: 2022

Publication City: Bozeman, MT

Publisher: Environmental Health News

Author(s): Joan Diamond, Paul Ehrlich

Our educational systems are failing to prepare people for existential environmental threats

“American collapse is ‘hypercollapse,’ made of bots and ‘fake news’ and hacked elections, not just demagogues and speeches, which are radicalizing people already left ignorant by failing education institutions and civic norms” (1)

A group of concerned climate scientists said in a recent wide-ranging peer-reviewed article: “In our view, the evidence from tipping points alone suggests that we are in a state of planetary emergency: both the risk and urgency of the situation are acute” (2) . Despite this, the deep, decades-old, and frequently voiced concerns of the scientific community have been generally ignored (3-7).

The warnings recently have been accompanied by the confusion and unnecessary deaths in the Covid pandemic, the increases in authoritarian rule threatening democracy in the United States and other countries, and the refusal of world leaders to deal with escalating climate disruption or with the presence of vast nuclear arsenals. The latter is now highlighted by Putin’s possibly civilization-ending invasion of Ukraine for which he threatens to trigger a holocaust.

All these events show something in common. They have jointly made crystal clear the utter failure of the educational system in the United States and most other rich countries to prepare people for the existential environmental threats that are consequences of the great acceleration – the recent surge in growth and technological capacity of the global human enterprise (8). As a single current example, how many “educated” people understand that the United States has been sinking vast amounts of money into “modernizing” its “nuclear triad” – its weaponry for fighting a nuclear war – thus increasing the odds of such a war, which would cause a terminal environmental collapse (9)?

A half century ago, when Joan Diamond was studying education, one of the core questions in the graduate curriculum was whether educational institutions should be designed to reflect the current society or should be vehicles for social change. In the face of ecological overshoot, increasing inequity, threats to democracy and civil rights (as evidenced by the Supreme Court ending Roe v Wade) and signs, we believe, of having lost our moral compass, it seems clear that in too many leading universities the former looks to be what is prevalent now.

It appears that most people don’t believe that a principal role of education should be to encourage social evolution to meet changing circumstances. To move schooling into that role there first needs to be discourse to determine what a healthy, sustainable society really needs, discourse that today is rare at best and that needs to be coupled with a clear vision of a compelling future, given the realities of the current human predicament.

Culture gap

One main reason for the lack of that discourse may be that the culture gap – the chasm between what each individual knows and the collective information possessed by society as a whole (10-12) – has never been larger and never more dangerous.

In the forager societies that were characteristic of the vast majority of human history, almost all adults understood how nearly everything “worked.” When PRE lived with the Inuit in 1952, every adult Inuit knew how komatiks (sleds) and igloos were constructed and seals were hunted, as well as the rest of their culture. Today in western culture none of us come remotely close to straddling the gap.

Could you describe the electronics that make a cellphone work or how an automobile is constructed from raw materials? Could most educated people even briefly describe crucial elements whose knowledge might put them on the survival side of the gap? Could they at least have some grasp of ecosystem services, the second law of thermodynamics, exponential growth, how the Nazis took over Germany, nuclear weapons and nuclear winter, or (in the U.S.) how the South “won” the Civil War? Would they be familiar with the biology of race and gender or the debates between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists? Does any aspect of today’s educational system have the goal of seeing that everyone ends up learning about and pursuing throughout life the aspects of culture that would make them understand the foundations of sustainability?

It’s important to remember that public education was originally established as an agent of change. It was part of the institutionalization of western societies along with population growth, industrialization, urbanization, and separation of home from workplace. Public education was designed to provide the wage laborers the capitalist system demanded, workers who would be punctual and who could read and calculate for the increasingly industrialized world. It still fills that need.

“Schools too often are carefully designed to prepare people for adult work roles, by socializing people to function well (and without complaint) in the hierarchical structure of the modern corporation or public office” (13).

Public schooling was not designed originally to produce “educated” people per se (14, 15) or as a way of somewhat reducing the already growing culture gap. It was a benefit for the rich rentier capitalists who employed wage earners, whose own children were educated privately, often in religious schools. That pattern of education-for-employment has changed too little today (16), as documented by even most of the wealthy.

Flagship institutions

A major reason for that is that those flagship educational institutions, colleges and universities pay relatively little attention to newly critical educational needs created by the acceleration. They don’t focus a major part of their efforts or influence on pre-college learning on what adults need to know to function positively in an increasingly complex endangered civilization.

This failure is reflected down the school apparatus, which mostly does not begin to prepare children to deal even with those two changing systems in our society of prime personal interest: the legal and medical systems. Nor are most Americans given enough information to understand the nature and impacts of the hierarchical and inequitable structures of modern society and the current trend of steepening the hierarchy (17-20).

It is difficult to learn in school how possibly to soften the impacts of inequity in the face of a storm of disinformation concerning those impacts, some both quite subtle and persistent such as the myth that different human groups possess importantly different genetic capabilities (21). The task is made more difficult in some American jurisdictions in 36 states where there are government-imposed legal barriers to passing on pertinent information about race and racism to children (https://bit.ly/3xyo8RN).

The process of education itself has become a silo in western civilizations, within which curriculum design and implementation appear to be more important to specialists than content (22, 23). The content element in that silo generally reflects an Aristotelian approach to learning, which originally focused on the teaching of subjects that were thought to improve the intellectual and moral development of individuals (and, with industrialization, prepare them to be obedient wage slaves). It divides what is to be learned into separate “subjects” and at the college level into separate “departments” through which funds, faculty promotions and perks flow.

Following Aristotle

Students at all pre-college levels are generally expected to be educated, again following Aristotle, in age groups, apparently on the implicit assumption that all 10-year-olds have similar interests and capacities. That can be seen implicitly in education today, which lacking a clear involvement in the social dangers of the great acceleration, diverges from Aristotle and tends to view learning as something that ends with a certification at a certain age: high school diploma, bachelor’s or master’s degree, doctorate, or perhaps some post-doctoral training.

A doctorate in biology earned in 1957 (as Paul Ehrlich’s was) would be close to useless to society today unless continually updated with learning. Most of today’s biological knowledge would be incomprehensible to Aristotle, should he suddenly reappear. Formal retraining throughout a career does occur in some areas (for instance, aviation, partially in medicine) but currency in a rapidly evolving world depends largely on individual initiative, ability to depart from past topics, and well-developed bullshit detectors (24).

The dramatic increase in the potential sources of education in the great acceleration – movies, radio, TV, the web, have been recognized by educators, as has been the need for passing on more kinds of “literacy” (25, 26). Leave it to the flexible Finns to recognize the serious consequences of the rigid “learn your subjects” approach to teaching. Finland is formalizing a new system of teaching: “In Phenomenon Based Learning” (PhenoBL) and teaching, holistic real-world phenomena provide the starting point for learning. The phenomena are studied as complete entities, in their real context, and the information and skills related to them are studied by crossing the boundaries between subjects” (27, 28). There have been forays into this style of curriculum in the United States, but, none, to our knowledge, that have been adopted by school districts and states as the formal curriculum. There is observational evidence that we have moved in the opposite direction—one designed for standardized testing.

Learning falls behind

Starting with the need for literacy and numeracy for industrialization, the environmental demand for specific kinds of education has paralleled the great acceleration. But despite heroic efforts in a few areas such as the development of textbooks by the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (29, 30), and a long interest in education in mathematics and its history (31) learning has fallen far behind need.

There are small colleges and departments that directly tackle these issues but they are not mainstream and are often marginalized. Just think, for instance, of the clear widespread ignorance of simple exponential growth illustrated by discussions of the Covid-19 pandemic and of demography in general.

Basic questions like what is education, what should be its purpose, and how should it be supported, should be major topics of concern, in colleges and universities as well as elementary and high schools.

But we can only touch on the basics here because of the immediate need for help from educational institutions both to close critical parts of the culture gap and to help mobilize civil society to deal with immediate existential threats to civilization. Educators need to provide leadership in explaining those threats in general, and right now because of Vladimir Putin, specifically to educate people to the world-ending possibilities of nuclear war.

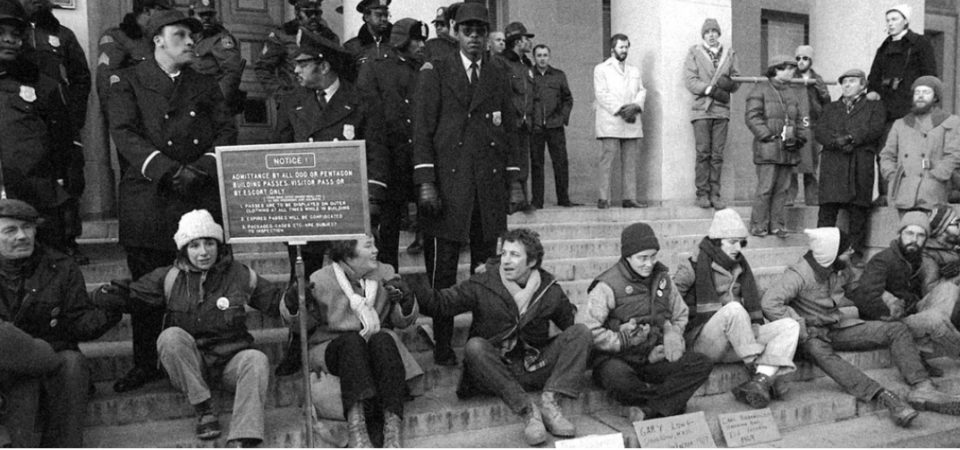

Indeed one of the most critical parts of the culture gap is the large number of people who, since 1945, remain ignorant of the potential impact of such a war and believe that wars fought with nuclear weapons are “winnable.” This ignorance is partly explicable because of a general failure of schools and public education to inform citizens of the risks leaders have taken, the near misses that civilization has lived through by pure luck, and the now increasing odds of total disaster. But can we attribute the absence today, in the face of much more serious consequences, of the protests and teach-ins that rocked universities during the Vietnam war to that failure of education, or purely to the lack of a draft?

Able Archer 83

It’s sometimes said that considering nuclear wars is thinking about the unthinkable, but many specialists have spent lots of time doing just that. For instance, military planning for a “protracted” nuclear war in which the U.S. “prevailed” and for which the American nuclear triad should be upgraded was much discussed during the Reagan administration (32, 33) and as a result of the “Able Archer 83” incident.

Able Archer 83 was what some consider to have been a “near miss” in 1983 when Russians suspecting the regular NATO Able Archer maneuvers were a cover-up for a sneak “first strike” nuclear attack on the Soviet Union. Soviet forces began readying for a nuclear response, but the issue never reached Leonid Brezhnev before the Russians determined there was no coming attack. He, like many in the American military hierarchy and unlike some of his subordinates, persisted in the view that a nuclear war would be insane – and impossible to win.

If nothing else the Able Archer 83 incident underlines now how the fate of civilization rests precariously on personalities, ideologies, intelligence accuracy, misunderstandings, and many other features of human behavior and human cultures that make the very existence of weapons of mass destruction, nation-states, and war itself increasingly problematic (11, 34, 35). But whether a “limited” nuclear war is possible is still discussed, even after the “Proud Prophet” war games long ago showed how unlikely it was to avoid escalation from the use of “battlefield” weapons to complete strategic disaster (36-38).

After a period of relative quiet on the issue, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has rekindled the debate, with at least on the political side, apparent great ignorance of the issues. The latest Pentagon budget, in which huge amounts of money are transferred to corporate oligarchs for the modernization of the useless and dangerous U.S. triad (9) suggests that such attitudes are alive and well at the higher levels of government in the United States. Vladimir Putin’s statements make it clear they are thriving among some in the Russian leadership as well.

Existential threats

Education systems around the world should be pressing to get people to understand what’s at stake with the existence of thousands of nuclear weapons, and not just because Putin threatens to use them. For example, it seems certain that even today there are powerful people in the governments of India and Pakistan who believe nuclear weapon use is at least riskable and perhaps winnable (39), Should India and Pakistan have a nuclear exchange, it also seems likely civilization would perish (40).

And behind the now immediate nuclear threat is an array of other existential threats (41), including other weapons of mass destruction, knowledge of which lies on the far side of the culture gap and is not explained even to everyone enrolled in research universities.

One can learn important things from the state of those universities. Many of them, for instance, have business schools “places that teach people how to get money out of the pockets of ordinary people and keep it for themselves” (42). Money issues control virtually everything at universities as they do in most “modern” societies. Stanford University’s academic senate gave a great lesson in the need to change the financing of higher education by refusing to divest from the fossil fuel industry because some senators were getting research support from them. The best short summary of what’s wrong with universities we have seen is that they are “too busy oiling the wheels to worry about where the engine is going.” More or less the same is said here in a more amusing form.

There are of course many efforts out there to transform education—especially the work of pioneering individual faculty who would like to change the world even if their institutions remain mired in the 19th century. Stanford led there by establishing its Human Biology Program in 1971 and the Center for Conservation Biology in the Biology Department in 1984. There have been established other well-meaning programs to foster “social transformation” (including efforts to develop “social innovation curricula” in business schools), and some initiatives designed to deal with the fundamentals of the existential threats.

But a glance at the literature (e.g., (43-45) suggests changes in higher education even in rich countries are unlikely to be spearheaded by academics. Too many teachers themselves have little grasp of the nature or magnitude of the problems of growth mania, revealed by our species’ history (11). They don’t recognize how short is the time available to have a reasonable chance of solving the problems, or how early in school and public education dramatic changes to teach about them would be necessary. This is unsurprising since the teachers are, obviously, products of the broken system.

Prominent buzzwords

Meanwhile, mainstream higher education persists in making things worse. Stanford ironically recently created an example of how not to catch up with Finnish middle schools educationally. Recognizing that climate disruption was a major concern and that “sustainability” was becoming a prominent buzzword, a move developed, especially among engineers and geologists, to establish a new School of Sustainability –originally labeled the School of Sustainability and Climate.

The idea was, of course, basically to raise money.

Academically it was silly from the start, simply because it retained or added more departmental and other anti-intellectual organizations to the university, rather than re-examining the institution’s entire structure, its role in a dissolving civilization, and the consequences of its means of support. It’s worth a glimpse at the new school’s current structure which shows both its siloing and the near absence of understanding of the basic issues of sustainability.

For instance, the sine qua non of sustainability is humanely and equitably reducing the scale of the human enterprise, both the numbers of people and the average consumption per capita (46-48). As you can see there is not a hint of this in the new school’s structure and there are many hints of ignorance in its announcement. For instance, the announcement says the school will “address the planet’s sustainability,” but Earth’s sustainability has never been thought to be even slightly in jeopardy (at least for the next few billion years). The social sciences division of the school will “discover the causes of sustainability challenges, innovate new solutions to these challenges.”

Of course, the causes are already extremely well known – maybe the school could “innovate an old solution” and get the business school closed down (or at least it could hire writers who know English.) We could go on about things like how much more important humanities (absent from the school) are to sustainability than geophysics, but we’ll spare you. The Doerr school is a monument to what’s wrong with universities as civilization circles the drain, and analyzing its structure would be a valuable learning experience for freshmen wishing to understand how close we are to going down that drain.

Civil society

On the other hand, obviously many non-pedants in civil society are deeply concerned and understand the need to shrink the scale of the human enterprise.

Many couples globally are choosing to stop at one child or go childless, steps in rich countries that are are major personal contributions to sustainability (49). And there are many organizations in civil society that “get it” – from ZPG in the old days to Growthbusters, the Post-Carbon Institute, Population Media Center, Global Conservation, and the Global Footprint Network today. And of course, there’s the MAHB that probably does more than those other fine NGOs to engage broad civil society. It doesn’t just serve those who already understand the existential threats, but also those who wish to understand them better and develop ways to counter them.

The challenge is that scaling up these efforts, understanding the barriers, and converting their message into policy in the face of near boundless ignorance and organized denial is not easy. But there is a lot of good stuff happening. Not at the necessary scale. Too quiet. Sometimes too afraid. But sometimes not.

Despite the manifest flaws in education that will need to be corrected if there ever is to be a Civilization 2.0, there are things universities could do now if they ever are awakened from their slumber. Where is the modern-day equivalent of the teach-ins of the 70s —now needed on nuclear weapons history and potential impacts of other doomsday weapons, on climate disruption, on the scale of the human enterprise and population imperatives, on the genetic disinformation on race and gender, on the need to modernize the constitution, on extinction and loss of ecosystem services, on the demographic and biodiversity elements of pandemics, on the financialization of value and the requirement for wealth redistribution, on the ethics of borders and sharing the burdens of refugees, on the roots of human dominance in the evolution of empathy, and on dozens of other topics about which most “educated” Americans are clueless?

Where are the classes being canceled or suspended to make time for the development of new education attuned to the greatest crisis humanity has ever faced? Where are the university presidents to give intellectual leadership in the worst time of human history, a time when the potential ultimate war is being fought in Europe and for the first time a global civilization is teetering on the brink of collapse? Why are universities not loudly criticizing the media’s “news” focus on political maneuvering, crime, celebrity doings, sporting events, gasoline prices (without mentioning the need to get them higher), and keeping the economic cancer growing while virtually ignoring the existential threats? Where are the students demonstrating as their futures are being mortgaged further each day by unsustainable population growth and over-consumption (48)?

How many economics students organize protests over departments not teaching the obvious – that economists who think that population growth can continue indefinitely along with escalating universal wealth and consumption are daydream believers? One answer according to famed anthropologist Marshall Sahlins is that the overall cultural background in which the universities are embedded is inimical to leadership actions (50). In 2009 Sahlins suggested a part of the problem was the popularity of business courses. Could part of today’s more desperate problem be the overwhelming popularity of computer science?

Our current education system –right up to the university—is trapped in reflecting society and missing the imperative to change human culture. As such it drives rather than solves the problems facing us, especially as it is so largely financed by politicians, and worse yet, corporations and rentier capitalists and their own sadly mis-educated products (think again economics departments and business schools and add in law schools).

And as you can see, this system of support is loaded with pitfalls and contradictions.

But we think universities should still speak from the lens of progressive human values and ecological well-being—to try to create the educational base for a strong, sustainable society with more equity, laws that evolve with the acceleration and do not overweight originalism), and near-universal well-being as goals. It is clear to us that getting key parts of the culture gap closed is an essential task for civil society if it aspires to those goals, and thus for a modernized educational apparatus led by universities and perhaps a vastly scaled-up MAHB-type civil society to nurture it.

References

1. Haque U (2018) (Why) American collapse is extraordinary: Or, why America’s melting down faster than anyone believed. Eudaimonia.

2. Lenton TM, et al. (2019) Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. (Nature Publishing Group).

3. Union of Concerned Scientists (1993) World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity (Union of Concerned Scientists, Cambridge, MA).

4. National Academy of Sciences USA (1993) A Joint Statement by Fifty-eight of the World’s Scientific Academies. Population Summit of the World’s Scientific Academies, (National Academy Press).

5. Ceballos G, Ehrlich AH, & Ehrlich PR (2015) The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD).

6. Ripple WJ, et al. (2017) World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice. BioScience 67(12):1026-1028.

7. Rees WE (2020) Ecological economics for humanity’s plague phase. Ecological Economics 169:106519.

8. Steffen W, Broadgate W, Deutsch L, Gaffney O, & Ludwig C (2015) The trajectory of the Anthropocene: the great acceleration. The Anthropocene Review 2(1):81-98.

9. Kristensen HM, McKinzie M, & Postol TA (2017) How US nuclear force modernization is undermining strategic stability: The burst-height compensating super-fuze. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

10. Ehrlich PR & Ehrlich AH (2010) The culture gap and its needed closures. International Journal of Environmental Studies 67(4):481-492.

11. Ehrlich PR & Ehrlich AH (2022) Returning to “Normal”? Evolutionary Roots of the Human Prospect. BioScience 72(8):778=788.

12. Ehrlich PR & Ornstein RE (2010) Humanity on a Tightrope: Thoughts on Empathy, Family, and Big Changes for a Viable Future (Rowman & Littlefield, New York, NY).

13. Bowles S & Gintis H (2011) Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life (Haymarket Books).

14. Katz MB (1976) The origins of public education: A reassessment. History of Education Quarterly 16(4):381-407.

15. Carl J (2009) Industrialization and public education: Social cohesion and social stratification. International handbook of comparative education, (Springer), pp 503-518.

16. Bills DB (2004) The sociology of education and work (Blackwell Pub.).

17. Mayer J (2016) Dark money: The hidden history of the billionaires behind the rise of the radical right (Anchor).

18. Stevenson B (2019) Just Mercy (Movie Tie-In Edition): A Story of Justice and Redemption (One World).

19. Eberhardt JL (2020) Biased: Uncovering the hidden prejudice that shapes what we see, think, and do (Penguin Books).

20. Snyder T (2021) On Tyranny Graphic Edition: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (Random House).

21. Feldman M & Riskin J (2022) Why biology is not destiny. New York Review.

22. Prideaux D (2003) Curriculum design. Bmj 326(7383):268-270.

23. Jacobs HH (1989) Interdisciplinary curriculum: Design and implementation (ERIC).

24. Kluger B (2020) The Medical Bullshit Detector Part I: Untrustworthy Products and Unbelievable Ideas.

25. Anstey M & Bull G (2004) The Literacy Labyrinth second edition. Frenchs Forest. New South Wales: Pearson Education Australia.

26. Kulju P, et al. (2018) A review of multiliteracies pedagogy in primary classrooms. Language and Literacy 20(2):80-101.

27. Silander P (2015) Phenomenon based learning. Retrieved August 1:2018.

28. Symeonidis V & Schwarz JF (2016) Phenomenon-based teaching and learning through the pedagogical lenses of phenomenology: The recent curriculum reform in Finland. Forum Oświatowe, (University of Lower Silesia), pp 31–47-31–47.

29. Glass B (1962) Renascent biology: A report on the AIBS biological sciences curriculum study. The School Review 70(1):16-43.

30. Grobman AB (1984) AIBS News. BioScience:551-557.

31. Kilpatrick J (2020) History of research in mathematics education. Encyclopedia of mathematics education:349-354.

32. Rogers CR (1982) A psychologist looks at nuclear war: Its threat, its possible prevention. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 22(4):9-20.

33. Halloran R (2008) Protracted Nuclear War. Air Force Magazine 91(3):57.

34. Mastny V (2009) How Able Was “Able Archer”?: Nuclear Trigger and Intelligence in Perspective. Journal of Cold War Studies 11(1):108-123.

35. Scott L (2013) Intelligence and the risk of nuclear war: Able Archer-83 revisited. Intelligence in the Cold War: What Difference did it Make?, (Routledge), pp 15-33.

36. Pauly RB (2018) Would US Leaders Push the Button? Wargames and the Sources of Nuclear Restraint. International Security 43(2):151-192.

37. Bracken P (2012) The second nuclear age: Strategy, danger, and the new power politics (Macmillan).

38. Davis PK & Bennett BW (2022) Nuclear-Use Cases For Contemplating Crisis And Conflict On The Korean Peninsula. Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament:1-26.

39. Jayaprakash N (2002) Winnable Nuclear War? Rhetoric and Reality. Economic and Political Weekly:196-198.

40. Toon OB, et al. (2019) Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe. Science Advances 5(10):eaay5478.

41. Bradshaw CJ, et al. (2021) Underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future. Frontiers in Conservation Science 1:61549:9.

42. Parker M (2018) Shut Down the Business School (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL).

43. Kumari R, Kwon K-S, Lee B-H, & Choi K (2019) Co-creation for social innovation in the ecosystem context: The role of higher educational institutions. Sustainability 12(1):307.

44. Solís-Espallargas C, Ruiz-Morales J, Limón-Domínguez D, & Valderrama-Hernández R (2019) Sustainability in the university: A study of its presence in curricula, teachers and students of education. Sustainability 11(23):6620.

45. Galego D, Soto W, Carrasco G, Amorim M, & Ferreira Dias M (2018) Embedding Social Innovation in Latin America Academic Curriculum. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances, Valencia, Spain, pp 20-22.

46. Ehrlich PR & Ehrlich AH (2013) Can a collapse of civilization be avoided? Proceeding of the Royal Society B.

47. Rees W (2020) The fractal biology of plague and the future of civilization. The Journal of Population and Sustainability Online 9 December.

48. Dasgupta P, Dasgupta A, & Barrett S (2021) Population, Ecological Footprint and the Sustainable Development Goals. Environmental and Resource Economics:1-17.

49. Wynes S & Nicholas KA (2017) The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environ Res Lett 12(7):074024.

50. Sahlins M (2009) The Teach‐ins: Anti‐war protest in the Old Stoned Age. Anthropology Today 25(1):3-5.

Article republished with permission.

Joan Diamond is the Executive Director of Stanford University’s Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere (MAHB) and of the Crans Foresight Analysis Nexus (FAN).

Paul Ehrlich is the Bing Professor of Population Studies Emeritus and president of the Center for Conservation Biology at Stanford University.